Groundbreaking Donatello

A landmark exhibition ‘Donatello, The Renaissance’ opened on 19 March at the Palazzo Strozzi and at the Bargello Museum in Florence, Italy. It is the first ever exhibition which brings together all major works by the Florentine sculptor Donatello (born in 1386), with loans from over 50 museums and institutions across the world. The exhibition features around 130 sculptures, paintings and drawings by both Donatello and by artists who were influenced by him, including Michelangelo, Giovanni Bellini, Leonardo da Vinci and Artemisia Gentileschi.

Why was Donatello so revolutionary? Donatello is often considered one of the artists who paved the way for the Italian Renaissance. His extensive knowledge of ancient Roman and Greek sculptures, combined with his technical abilities in both bronze and marble, allowed him to bring a vivid expressivity to his works. In each of his sculptures, modern viewers are presented with stark and powerful emotions which seem to bridge the gap between modern and historical worlds.

Donatello was constantly experimenting. He developed his own style of relief which was known as schiacciato (‘flattened out’), by using the light and shadow created by shallow carving to create a vivid three-dimensional effect. Donatello was the first sculptor to use the single vanishing-point perspective system in relief sculpture, and he produced artworks in a wide range of media, from stone, metal and wood to terracotta, glass, wax and bronze…

5 sculptures in 5 different materials by Donatello…

Donatello, The Feast of Herod, c. 1427, Bronze, 60 x 60 cm, Baptistery, Siena (Image: WGA)

Bronze

The Feast of Herod, c. 1427

Some of Donatello’s best known works are made in bronze - most famously his David, made around 1440, and one of the stars of the new exhibition (it was also the predecessor to Michelangelo’s marble David). Many years earlier, around 1427, Donatello made one of his first gilded bronze relief sculptures, The Feast of Herod, for the baptistry of the Siena Cathedral. It shows the Banquet of Herod, in which a kneeling soldier presents the head of John the Baptist on a golden platter to King Herod. As Herod holds his hands up in horror, two children next to him can be seen running away from the scene.

By including architectural elements in the scene, Donatello incorporates linear perspective, as developed by his contemporary Filippo Brunelleschi (who designed the dome of Florence’s Cathedral). It allows him to create a multi-layered scene filled with different figures - some are actively shocked by the horror of John the Baptist’s head on a platter, but others in the background (such as the musicians seen through the window) are, by contrast, seemingly oblivious. This relief sculpture is one of the works displayed in the exhibition which has never been seen in a public institution before (which has been an opportunity for restoration).

Donatello, The Penitent Magdalene, c. 1453-55, polychrome wood, height 188 cm, Museo dell'Opera del Duomo, Florence (Image: Wikipedia)

Donatello, The Penitent Magdalene, c. 1453-55, polychrome wood, height 188 cm, Museo dell'Opera del Duomo, Florence (Image: Wikipedia)

Wood

The Penitent Magdalene, c. 1453-55

Donatello made this wood sculpture depicting Mary Magdalene around 1453-55, most likely as a commission for the Baptistery of Florence. Contemporaries were astounded by the unprecedented realism with which Donatello represented Mary. Unlike other depictions which showed her as a beautiful young woman in full health, here Donatello chooses to show Mary as an emaciated, bedraggled figure - in line with the narrative that, having repented, she spent thirty years as a hermit in the desert. Even today, around 570 years after this sculpture was made, there is a sharp poignancy and desperation in this depiction of Mary - her gaunt face, matted hair and bony limbs almost become a universal image of human isolation and poverty.

Donatello, Pazzi Madonna, c. 1420, marble, 75 x 70 cm, Staatliche Museen, Berlin (Image: WGA)

Marble

Pazzi Madonna, c. 1420

This marble relief was made around 1420, and apparently was housed in the Palazzo Pazzi in Florence. The pose of the Virgin Mary in profile pressing her nose against her Child’s face not only clearly references the imagery of classical antiquity, it also conveys a powerfully intimate bond between the two figures. This moment of connection is emphasised by the seemingly simple marble framework - which, in fact, again makes use of linear perspective techniques. This particular technique of rilievo stiacciato (flattened relief) was developed by Donatello himself, and it remains fascinating that a physically flattened surface can contain so much depth (both visually and emotionally).

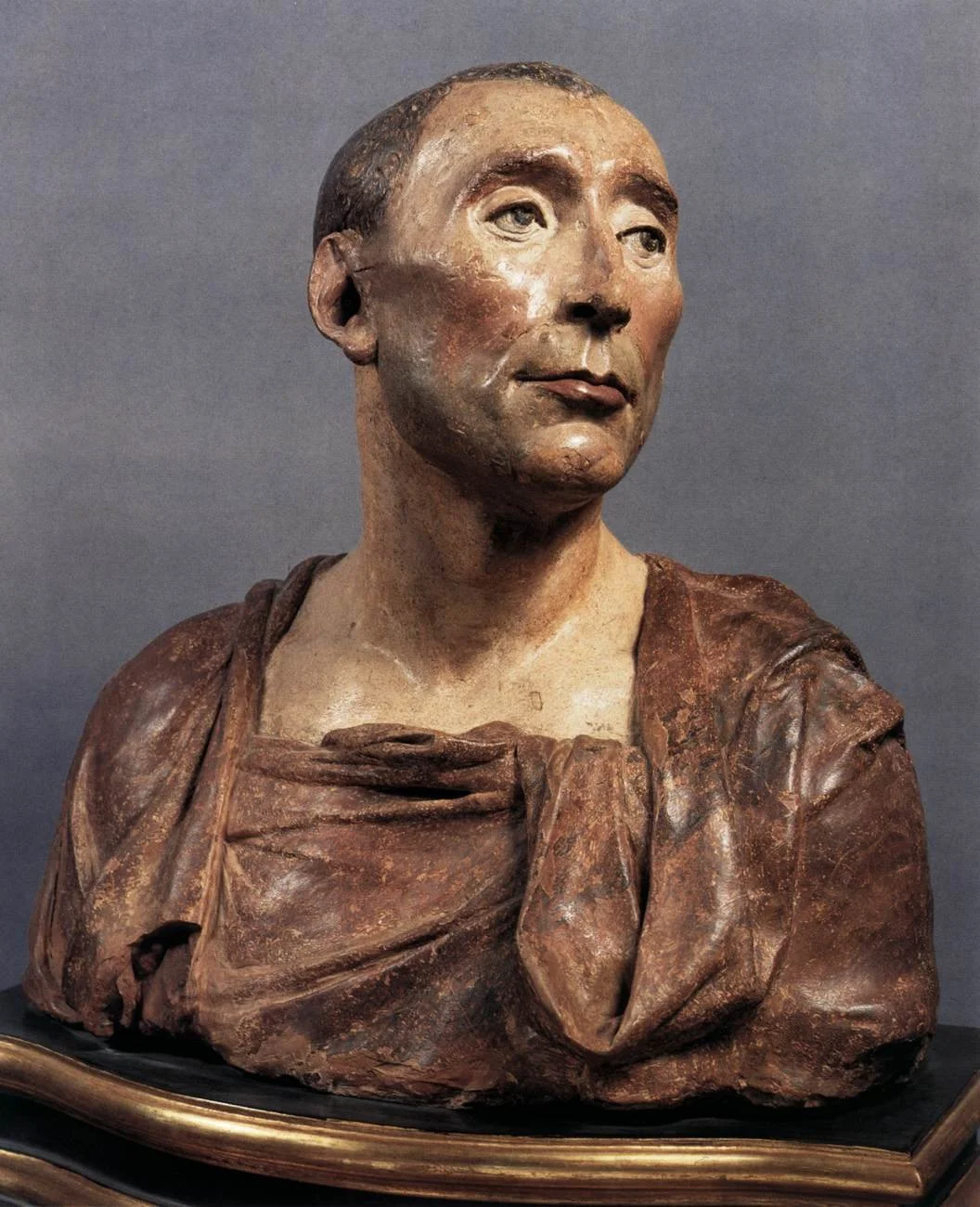

Donatello, Bust of Niccolò da Uzzano, c. 1432, polychrome terracotta, height 46 cm, Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Florence (Image: WGA)

Terracotta

Bust of Niccolò da Uzzano, c. 1432

This terracotta bust - with its original polychromy (colour) - seems to bring to life its sitter, the leading politician in Florence at the time, Niccolò da Uzzano. It is assumed that Donatello sculpted the bust after Niccolò’s death in 1431, by basing the likeness on a death mask. Donatello’s use of terracotta was unusual for the time. Although this type of clay had historically been used as a sculptural material across the ancient world (for example, in Chinese pottery from 10,000 BCE and Greek pottery from 7,000 BCE), it was not commonly used in European medieval art. It was only during the Italian Renaissance that the material saw a revival, initiated in large part by Donatello. Terracotta’s versatility and durability allowed sculptors such as Donatello to capture incredible detail, texture and startlingly realistic likenesses, as this bust perfectly demonstrates.

Mixed media

Piot Madonna, c. 1440 or c. 1460

This sculptural roundel is a fascinating mixture of media that encapsulates Donatello’s willingness to experiment with his art throughout his career. Primarily sculpted out of polychrome terracotta, this roundel also includes inlays of glass and wax. Again we see clear evidence of Donatello’s ability to reimagine and develop familiar subject-matters on both technical and visual levels (the glass and wax inlays create a depth and interest at which viewers can still marvel).

Donatello, Piot Madonna, c. 1440 or c. 1460, polychrome terracotta with glass and wax inlays, Musée du Louvre, Paris (Image: Wikipedia)

The exhibition is now open in the Fondazione Palazzo Strozzi and the Musei del Bargello until 31 July 2022. Learn more about visiting here.

The Staatliche Museum in Berlin will host its own version of the exhibition from 2 September 2022 to 8 January 2023, and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London will also stage its exhibition in 2023.

April 2022