Pierre Louis Alexandre

by Mats Werner

The registration card (below) is from the Catholic parish of St Eric in Stockholm around the turn of the 20th century, and it contains the essential facts about the life of artist’s model Pierre Louis Alexandre: his name, the fact that he was Black, his date of birth (one of them), that he was a dock worker and that he was a French citizen.

The date on top is supposed to be the time of his arrival in Stockholm, but since the card has been rewritten a number of times it could be a miswriting or misinterpretation of someone else’s handwriting. Not to be fully trusted, in other words. The card further tells us that he was married for the second time (the first marriage was of no consequence for the Catholic Church as it was carried out in a Protestant church) and that he died in Stockholm on April 29th 1905 and was buried in the Catholic graveyard just outside Stockholm on May 3rd.

According to the marriage journal, the two children from his second wife were registered as ”born within the marriage” which, together with other indications, makes me rather convinced that these were his own natural children, although conceived while he was still married to his first wife (who obviously could not become pregnant). The above card also gives the information that the two children belong to the parish.

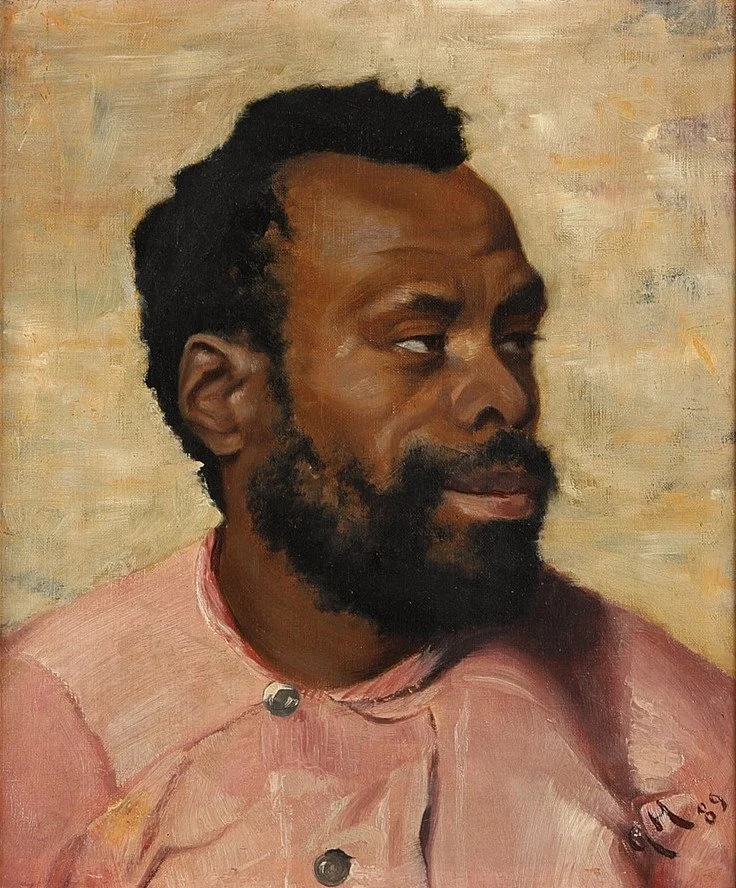

A previous article by Esme Garlake at Athena Art Foundation was mainly based on earlier findings from my research around Pierre Louis Alexandre, which started already in the 1970s and therefore needed updating after the publishing in 2021 of my book ”Svarte Peder / Negern Petterson – från Cayenne till Nationalmuseum”. The article, however, established something about Pierre Louis which was rather interesting. When I started asking questions about ”Negern Petterson” – which was his nickname when working as a model in the Royal Academy of Arts in Stockholm (I will return to that subject), nobody had any idea about who he was, if that was his real name, where he came from, if he lived in Stockholm or anything. None of the art museums like the National Gallery or any of the major auction houses had ever even given the question a thought even if there had been a few works sold during the years. So the work I have been putting into this project has resulted in Alexandre most likely being the one artist model in the world that we know so much about and – as Esme Garlake puts it: “there are around 40 (today: 48) surviving works in which Pierre is the model, dating from between 1878 to 1903 in Stockholm – which probably makes him the Black sitter about whom we have the most images in pre-20th-century art.”

My interest in ”Negern Petterson” (“The Black Petterson”) started early, as I grew up with the painting of him by Karin Bergöö hanging on the drawing-room wall at home. My father was the lawyer of the Bergöö family, and he got the painting as payment from Karin Bergöö’s nephew in the 1920s. It has been in the family ever since and is now on my own wall. It was always referred to as “Negern Petterson” by Karin Bergöö herself. So that was what I had to start with.

In 1996, the National Gallery of Sweden arranged an exhibition called “Främlingen – dröm eller hot” (The Stranger – Dream or Threat). As they did not have any painting with Alexandre as a model, they had to borrow one, made by Oscar Björck, from a private owner. The two curators, Jeanette Rangner and Hans Öjmyr, had spent a few hours in the archives of the Royal Academy of Arts and made the first discovery of a couple of receipts indicating the name of the model as possibly being Pierre-Louis or Jean-Louis Pettersson. But as I myself many years later went through all the verifications between 1863 and 1905 in the academy archive, I found many more and could also omit at least one of the receipts that Rangner/Öjmyr referred to (since it was signed “Lovis Pettersson”, which was a female model). But there is only one receipt where the name Petterson is used, and this is the first one that Pierre Louis signs in 1878. After that he just signs “Pierre”, “Pierre Louie” and later “P.L. Alexandre”. So how and why the nickname “Petterson” came into his life – and ours – remains a mystery. But it was obviously commonly used and is found as the name on more of the paintings made by other academy students.

It was not until some years later that I could finally identify his full name as Pierre Louis Alexandre. I connected the story of a coal miner employed by AB KOL & KOKS (who had also been a model for the painting by Edward Forsström) with the story of how this same employee found his wife hanging from a beam in an outhouse, having killed herself, and then found the police report on the incident. The coal miner was Pierre Louis Alexandre. After that, everything was easy. Having a name opens the official archives about where people lived, not to mention the archive of the Catholic Church. I could follow his actual movements around Stockholm. Apart from a year when he lived in the old town, he spent all his Swedish life in various locations on Södermalm (the southern island). He worked in the harbour which was mainly situated on the northern part of Södermalm and on both sides of the old town. But as the ice during the hard winters of the late 1800s made it impossible for sailing ships or the small new steamers to come into the Stockholm archipelago, the harbour was simply closed between mid-December and April-May. During this period, all the workers had to find something else to do. It is understandable that such a life must be extremely hard on people and relationships. Especially since there was a “comforting and warming” tavern on every corner. The alcohol problem was overall a great problem and killed many men and relationships during these years.

Pierre Louis, however, had a landlady who was an elderly relative to the young academy student Pauline Neumüller and she probably told Pierre Louis to contact the Academy, since Orientalist art had become fashionable. So he was hired as a model almost every winter from 1878 until 1903, when his tuberculosis probably made it too difficult for him to pose. And sometimes he had sittings in private studios or also in the Technical High School (today’s Konstfack). Instead of freezing in the harbour for minimum wages, he could sit or stand still inside (perhaps not the warmest of indoor places, but still) and for double the money! I am convinced he was a lucky guy and knew it.

Among the students who depicted him during the years, one should especially note Anders Zorn (who got an academy award for his little watercolour; see above), Oscar Björck, John Bauer and of course (the best of them all, if you ask me) Karin Bergöö, who later married Carl Larsson. Karin, like so many other female artists of the time, had to give up their own artist career after marriage, in order to manage their home and children. Many have said that Karin, if she had been allowed to continue painting, probably would have surpassed her husband. Karin, however, channelled her creativity in new ways, becoming the icon of the Swedish arts and crafts movement. When she encouraged Carl to use his time at home to depict the family country home and life in Sundborn Dalarna, the light and colourful interiors she had created were spread all over Europe and gave inspirations to many generations of young people settling into new homes. On the whole Pierre Louis seemed to have been a proper and hard-working man. It was said about him that “he was strong as four ordinary stowers, merry, ambitious, sober – on the whole an unattainable ornament for the stevedores guild” (according to P.L Lindgren’s records of tales and legends in the Stockholm Harbour, kept in the City Archive of Stockholm).

Pierre Louis was first married to Kristina Erikson in 1879. She was a factory worker. It seems that she was unable to have children, which made life hard for her and she periodically fell into depression and was also once hospitalised. In 1889, she committed suicide. A few years later Pierre Louis remarried, this time with Althea Wikman to whom he remained married until his death in 1905. Althea already had a son and a daughter. Several circumstances around their marriage, how the Catholic parish treated the subject and how the children were named and referred to by his fellow harbour-workers, has given me the impression that those two children could actually have been Pierre Louis’ natural children. It would mean that he had been unfaithful to his first wife having an affair ‘on the side’. To speculate further, one could suspect that Kristina found out about the affair and about the children. If she had been sad about having no children, it could not have been easier to find out that her husband had two children with another woman and that it was in other words her ‘fault’ that they did not get any children, which of course could have added to her depression, eventually leading to the suicide. From the beginning, I knew of only the Karin Bergöö-painting. When my father passed away, my mother asked me to empty the storerooms in the basement, as there had been problems with burglars. I went through and moved away a number of crates containing my father’s childhood memories, school-books, drawings, music sheets and other such stuff that had all been there, untouched, since they moved in 1933 when they got married. Far back, behind all the crates, a thick art-folder stood against the wall.

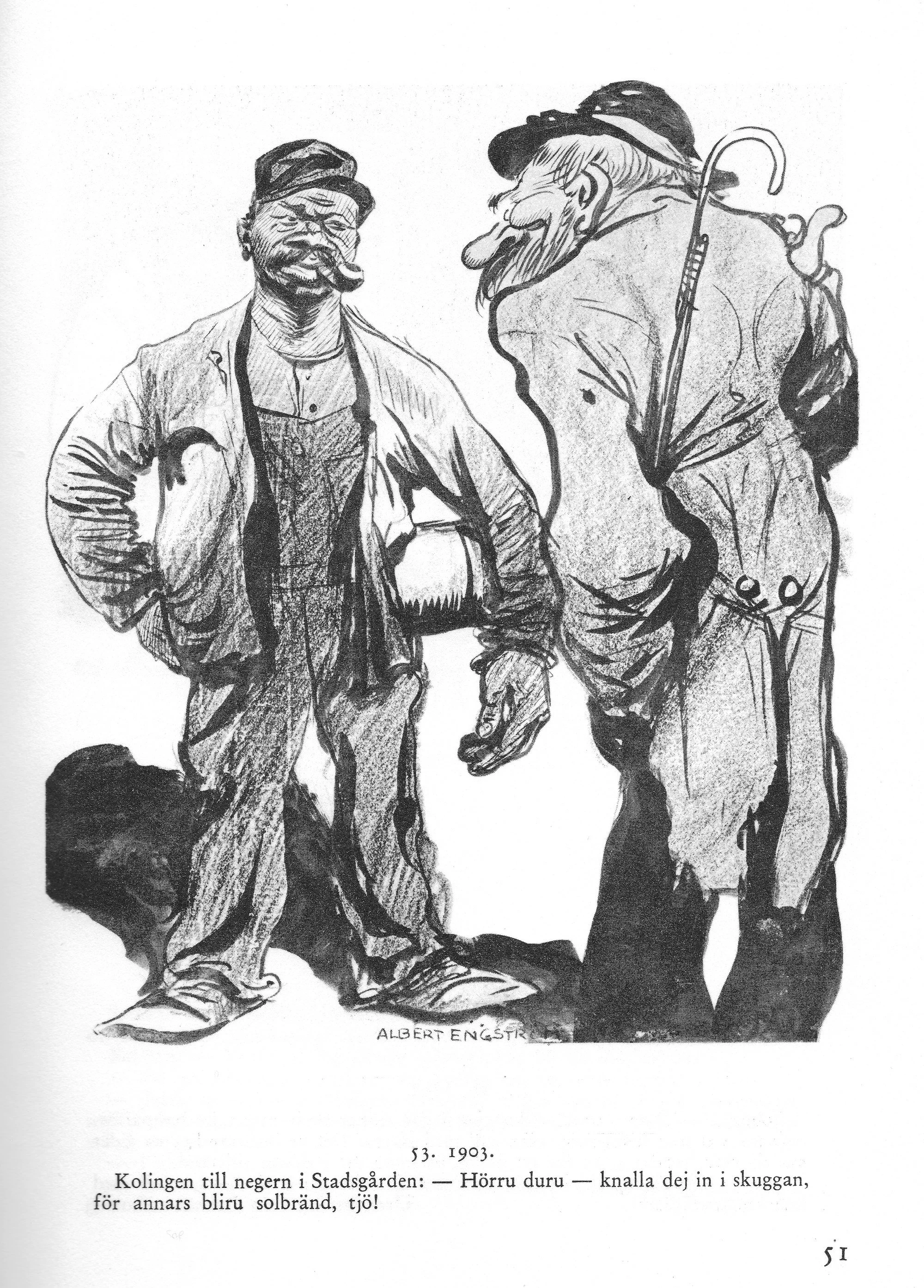

This was, of course, interesting. It contained a great number of academy studies of urns and antique ornaments in red chalk and nude sketches, further old etchings, drawings and some watercolours of various known and unknown artists. After a while I found that the nude studies were all signed by different female artists in the same class as Karin Bergöö, so I assumed that the folder also came from Karin’s academy years and that the classmates exchanged works as memories. But it also had later additions, possibly included when Carl and Karin Larsson spent time in the Bergöö home. For instance, when Carl executed the frescoes in the great dining room for his parents-in-law. Among these later additions were drawings by Albert Engström (see above), a watercolour by John Bauer and a drawing by Emil Österman depicting “Negern Petterson”, which became the second picture of “Petterson”, and which more or less started my search for other works of art with him as sitter.

My hunt for works of art with Pierre Louis as the model has been fun, interesting, often surprising and full of coincidences. Like when my new neighbour saw the Karin Bergöö painting through my window and said, “my friend has that painting at home as well!” It turned out to be a painting made by Alma Holsteinson at the same sitting as my painting and from a position next to Karin Bergöö’s. Fantastic coincidence. Without this neighbour, the owner would have never got in touch with me. The same happened when I found the owner of the Oscar Björck-painting from the exhibition in the National Gallery. Another friend of mine called and said that her cousin had a “Petterson”. By the time I was finishing the work with the book, I had found 43 works, of which two were sculptures and the rest oil paintings, watercolours or drawings. When I say “found”, it means that I know they exist and at best I have pictures of them, but in many cases I do not know who owns them or where they are located today. The last in the book catalogue I know belonged to the law partner of my father (or rather, his wife). I know who made it and on the whole what kind of sitting it was. I also know through which art gallery the family sold it. But no pictures exists, and the art dealer did not remember to whom he sold it... But one day it will certainly reappear. After the publishing of my book, at least five new works have surfaced as well as some that are probably not depicting Pierre Louis Alexandre, and before I add these in the catalogue I will make sure to be as sure as possible that they are “real Pettersons”.

Mats Werner is a Swedish writer and a retired pioneer in specialised international sales. You can read his blog here.

Note: all images courtesy of the author

April 2023