Africa & Byzantium: November Pick of the Month

The splendour of Byzantine artworks have long been celebrated, yet the impact that the visual culture of Africa had on it has not. Africa & Byzantium at The Met Museum is a landmark exhibition highlighting for the first time, the incredible contribution of Medieval African art on the Byzantine Empire and beyond. This month, we wanted to share with you our 10 favourite artefacts from the exhibition.

1. This 2nd century AD painting of the Egyptian goddess Isis was executed using tempera on fig wood. Interestingly, the hinges to the left of the work indicate that it may have originally been part of either a diptych or triptych. Also in the J. Paul Getty Museum is a matching work depicting the Graeco-Egyptian god Serapis (a conflation of Osiris and Apis), whose hinges are complimentary. In Ancient Egyptian religion, Isis’ domains included motherhood and fertility. Here, depicted in 3/4 view, she is reminiscent of depictions of the Virgin in Late Antiquity, reflecting the important impact that the art of North Africa had on the Christian art of the Eastern Mediterranean.

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

2. This vibrant diptych depicts Saint George and the Virgin with Child. Painted in Ethiopia between the late 15th and first half of the 16th centuries, the piece borrows from Italian works. Both iconographically and stylistically, the artist appears to have been inspired by Nicolò Brancaleon, an Italian painter who worked in Ethiopia with marked success. Here, the Virgin and Child are flanked by the archangels Gabriel and Michael, whilst the Saint is shown slaying the dragon. This imagery was a popular choice for artists across the Horn of Africa and Eastern Mediterranean.

The National Museum of African Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington D.C.

3. This 4th century AD textile depicts figures from Greek mythology. Here, a Satyr and Maenad embrace underneath an arch. Both of these figures were followers of the god Dionysus, accompanying him in his revelry. The positioning of their bodies implies movement, likely showing them dancing at some festivity. Another fragmentary textile, that may have been part of this same piece shows a second maenad playing a cithara (type of lute). Although this textile depicts Dionysian imagery, the owner likely did not worship pagan gods. Instead, it would have been valued as embodying social aspirations, and would have been displayed on a wall of a private home or in a public space.

The Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland.

4. Dating to between 1250 and 1300, this brass tray was probably made in either Egypt or Syria. Inlaid with silver and a black compound, the piece is engraved with a central sun disk that is surrounded by concentric decorative banding. Within these are the personifications of the twelve Zodiac signs and the six planets (the moon, Saturn, Venus, Jupiter, Mars, and Mercury). At the time it was made, astrological iconography was popular, and symbolised among other things, cosmic protection. The Arabic inscription informs us of the titles of a Mamluk official.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

5. This African red slip ware lagynos is an example of one of the most complex vessels made using a mold. The head of the oil flask is executed in striking detail, with each hair having been individually crafted by the artist using a trailed-slip technique. The piece would have been made using two or three different molds, whose contents would have been united before firing. The faces on African red slip ware were often well-known figures from Hellenistic mythology, exemplifying the popularity of Classical subjects in North Africa during Late Antiquity.

The Louvre, Paris.

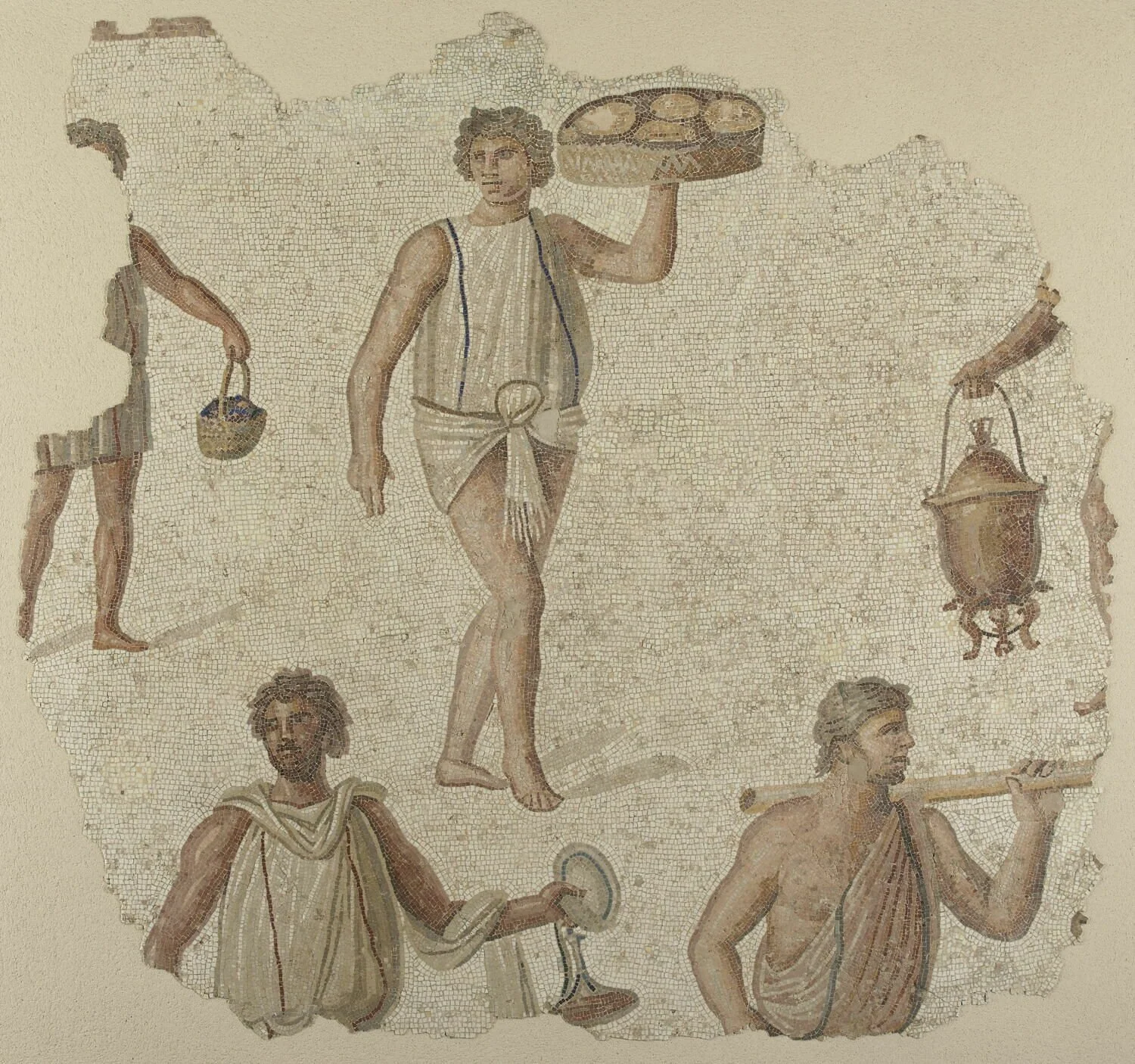

6. Discovered in 1875 near Carthage, in modern-day Tunisia, this mosaic would have been placed on the floor. It depicts several enslaved figures carrying preparations for a feast or festival. The mosaic is made up of different local materials, including limestone, glass paste, and marble. Dating to around 175-200 AD, the piece was unfortunately damaged during its removal post-excavation. Floor mosaics were carefully laid as flat as possible to create an even surface for walking, whilst mosaics placed on walls had their tesserae placed irregularly to maximise light reflection off the glass.

The Louvre, Paris.

7. Discovered alongside five other rock crystal artefacts in a Carthaginian cistern, this dish dates to between the 3rd and 5th centuries AD. Carved into the shape of a tholos temple. Its intended function remains unconfirmed, though it has been suggested that it was used as an incense burner. In antiquity, rock crystal was believed to have had prophylactic powers, and so been able to prevent disease. Because of this, it was a popular material for amulets and religious tokens, such as this cross pendant found near Thebes.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

8. Dating to the 5th-7th centuries AD, this textile fragment shows the goddess Artemis and the hunter Actaeon. These figures from Greek mythology are identifiable through their attributes, with Actaeon shown holding a reversed spear and wearing a Phrygian cap, and Artemis holding her distinguishing bow, poised for action. Here, both figures are shown with dark skin; a common theme in figural depictions on late antique Egyptian clothing and furnishings.

The British Museum, London.

9. During the Ptolemaic Greek and Roman periods in Egypt, indigenous deities became syncretized with Graeco-Roman ones. One such example is the goddess Isis, who was merged with Aphrodite, Fortuna, and Tyche.Dating to between 350-450 AD, this ivory box exemplifies this blend of religious and cultural identities. Its lid, shown here, depicts the aforementioned multi-identity goddess, whose symbols reveal the traditions they take from. Firstly, her crown of feathers with sun disk and cows’ horns are borrowed from Egyptian Isis. The Tyche-Fortuna elements are the cornucopia of abundance and the rudder with which she steers fate. Finally, taken from Aphrodite is the accompanying cupid holding a mirror.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

10. Although discovered in Egypt, this ornate gold neck ring is believed to have been made in the Byzantine capital, Constantinople, due to the depiction of the city personified on the reverse of the pseudo medallion. The piece, which dates to circa 539-550 AD, comprises of a hollow neck ring and coins surrounding a central medallion that all show Byzantine emperors. At the base of the piece are two rings from which a large medallion showing the emperor Theodosius I was once attached. It is believed that this imperial imagery suggests the piece was made using the military trophies of someone either belonging to the court or a renowned general.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

The exhibition is running until 3rd March 2024, tickets are included with museum entry.

(Written by Han Parker on behalf of Athena Art Foundation, November 2023)