A Pearl-Encrusted Account of ‘The Conquest of Mexico’: April Pick of the Month

La Luz del Nácar: Reflejos de Oriente en México, on at the Museo de América in Madrid until 25 May 2023, is a rare treat for anyone interested in the innovative art of early Modern Mexico, the hub of the Manila Galleon Trade linking the Far East, the Americas and Europe. The highlight of the exhibition is the complete series of Conquista de México, 24 panels in the enconchado technique from the Royal Collection combining oil paint and encrusted mother-of-pearl. This technique was developed in Mexico by artists responding to imported Japanese Nanban lacquerwares, popular with the local elite. Mexico had a plentiful supply of mother-of-pearl from oyster-beds off the coast of Baja California, as Hernán Cortés and the so-called conquistadores discovered when they encountered Pericú Indians wearing necklaces strung with red berries, shells and blackened pearls.

The exhibition opens with a selection of Namban objects and locally produced responses such as a 17th-century lectern with an image of the Virgin Mary painted onto a central mother-of-pearl plaque. Also in this section is a display of pigments, such as indigo and cochineal, as well as other materials and tools used to produce enconchado paintings. These materials were expensive and required knowledge of both the Early Netherlandish oil technique brought to Mexico by immigrant Spanish artists, and the highly-skilled work of preparing and inlaying the shell brought by Japanese craftsmen.

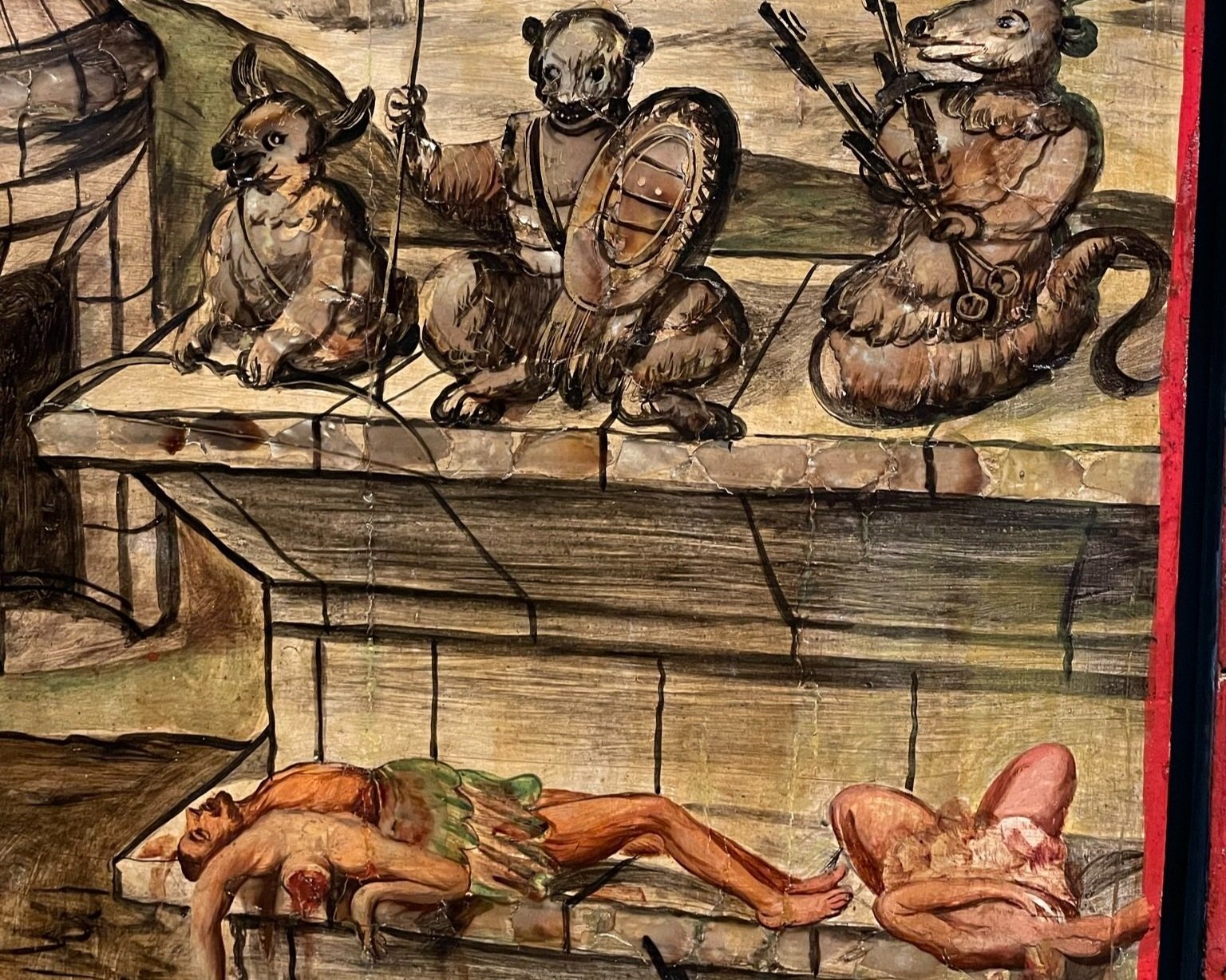

Wall labels (in Spanish only) explain that the first step in this technique - which was unique to Mexico and had died out by the 19th century - involved preparing a wood panel with gesso, just as a panel would be prepared for oil painting. Then a sketch of the scene would be laid onto it, with a decision made as to which areas would be painted in oil and which inlaid with fragments of mother-of-pearl. Oil paint was used for skin and still-life elements, whereas shell was applied to decorative areas such as garments and armour.

We can be reasonably sure that the subjects depicted in most enconchados were religious, on the basis of some 300 surviving examples. Very few of them are signed and we only know the names of about a dozen artists, but it is clear that they were organised in workshops involving several members of the same family. The series of 24 panels (see below) in the exhibition is dated 1698 and signed by Miguel and Juan González. These brothers belonged to the guild of painters and were the most accomplished of the ‘concheros’. Where they were born is not known, but another skilled conchero was Nicolás Correa whose mother is thought to have been of African descent and whose father is thought to have been a Morisco born in Cádiz. Correa’s fabulous Wedding at Cana (1696) is now in display at the Treasures from the Hispanic Society exhibition in London. These artists often used prints by Italian and Netherlandish artists as models.

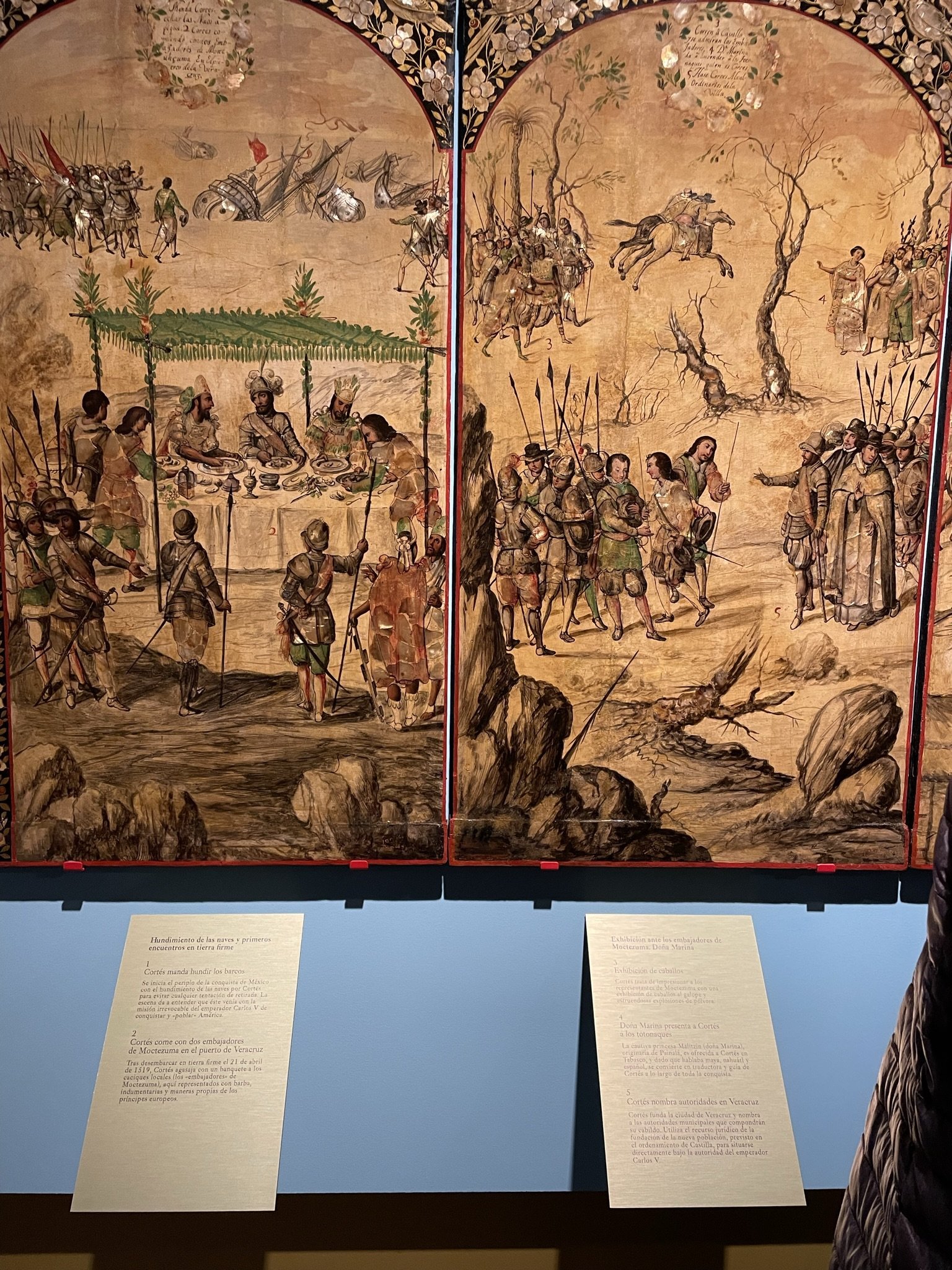

Miguel and Juan González, Conquista de México (panels 1 and 2), 1698, oil and mother-of-pearl on wood panel, Museo de América, Madrid (on loan from the Museo del Prado)

The 24 panels from the Royal Collection chronologically depict the story of the momentous events following the arrival of Hernán Cortés in 1519, as told by Spanish chroniclers such as Bernal Díaz del Castillo. The panels - now on display at the Museo de América - illustrate one or more numbered episodes (captions are provided in a small cartellino at the top of the panel). The first panel shows the sinking of the Spanish ships ordered by Cortés to avoid a mutiny and the tribute paid by the Aztec Emperor Moctezuma’s envoys according to the chroniclers’ descriptions. The second shows a display by Cortés of his horsemen as well as Doña Maria or La Malinche, a Nahuan woman who acted as an interpreter, advisor, and intermediary between the Spanish and the indigenous communities.

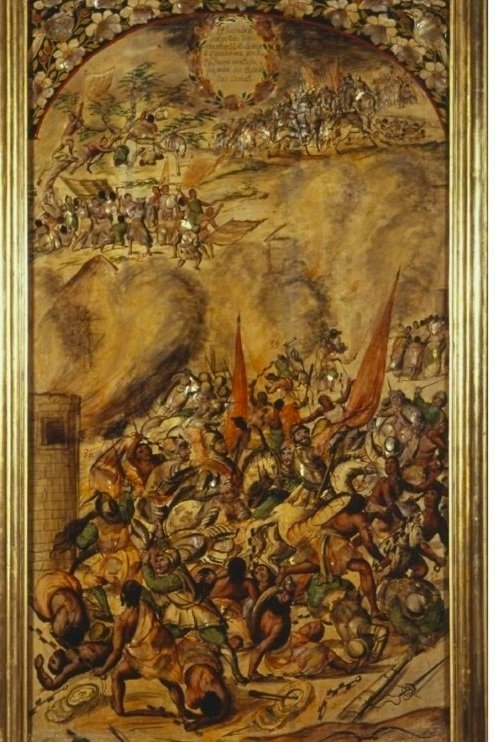

By the fifth panel, Cortés’s troops appear exhausted and we see images of human sacrifice performed by the indigenous peoples. In the following panels, we see the massacre of Cholula and ensuing submission of its rulers, baptism of local women, punishments inflicted on spies, and other episodes on the route to the Aztec capital. Panels 11, 12 and 13 are amongst the most spectacular, with Cortés entering the wondrous floating city of Tenochtitlán, Moctezuma caried on a palanquin to greet him and then receiving him in a Renaissance style palace with portraits of his ancestors hanging on the walls. The following panels show gift-giving, preaching and Moctezuma taken prisoner as some of his men trying to tear down a crucifix. The Aztecs, nevertheless, gain the upper-hand in the panel depicting the so-called Noche Triste (‘Sad Night’) when the Spanish are forced to retreat and Cuauhtémoc is crowned king. The model for this work was a print by the Italian artist Antonio Tempesta of Abraham Liberating his Nephew Lot.

A few panels later, Cortés himself is taken prisoner, but freed by the Spanish Cristóbal de Olea. Here we see combat with some of the indigenous soldiers carrying captured weapons and others with macuahuitl or swords made from obsidian. The final panels show the capture by the Spanish of Cuauhtémoc and the destruction of Tenochtitlán.

In recent years, the version of the events told in these panels has been revised to take account of indigenous voices; for example in Visión de los vencidos: Relaciones indígenas de la conquista. Nevertheless, these panels present an interesting viewpoint. By the time they were produced – some 180 years after the arrival of the Spanish – a new class of wealthy ‘criollos’ (descendants of the conquistadores) were pitted against the peninsulares or Spanish-born rulers. It may well have been members of this new class that commissioned the Conquista series to remind the Spanish of the role their ancestors had played in the establishment of New Spain, thereby justifying their own claims to power (indeed, the panels from the Royal Collection were sent as a gift to Charles II in Madrid). Along with the 24 panels from the Royal Collection on display in La Luz del Nacár, there are panels from two other series: six large panels acquired by the Museo de América from a private collection in Madrid in the early 20th century, and 24 panels from the collection of the Duques de Moctezuma (a hereditary title of Spanish nobility held by a line of descendants of Emperor Moctezuma II). The latter were commissioned by the last Viceroy of New Spain, who was himself a descendant of Moctezuma.

This is an important show for historians and art historians of the Early Modern period. Not only does it reveal the perspective of a group which would later play a key role in Mexican independence, but it makes us look again at an art form dismissed by some as purely decorative. It helps illustrate how the conquest of mexico went down. Above all, it highlights New Spain’s importance in the 17th century as a hub of artistic innovation. According to the publicity, the exhibition is part of a wider research project. Let’s hope there will also be a publication, and one that is available in both Spanish and English!

(Written by Dr Nicola Jennings on behalf of Athena Art Foundation, April 2023)