The Artist’s Model: Pierre Louis Alexandre

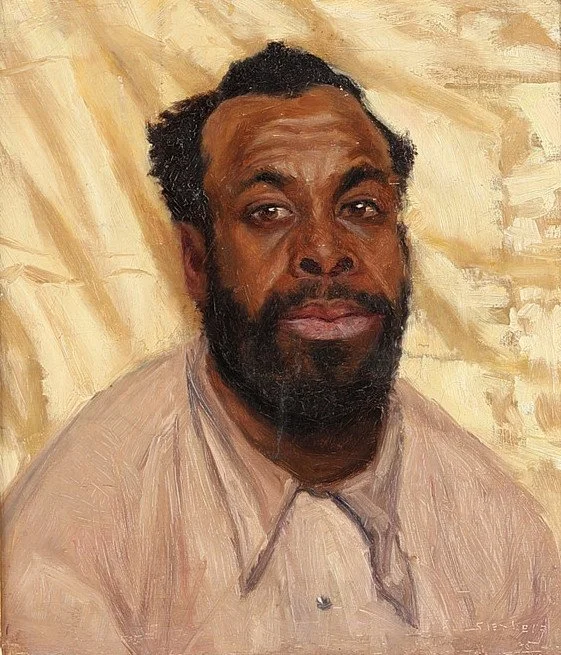

Emerik Stenberg, Portrait study, 1890, oil on canvas, 45 x 38.5 cm (Image: auctionnet)

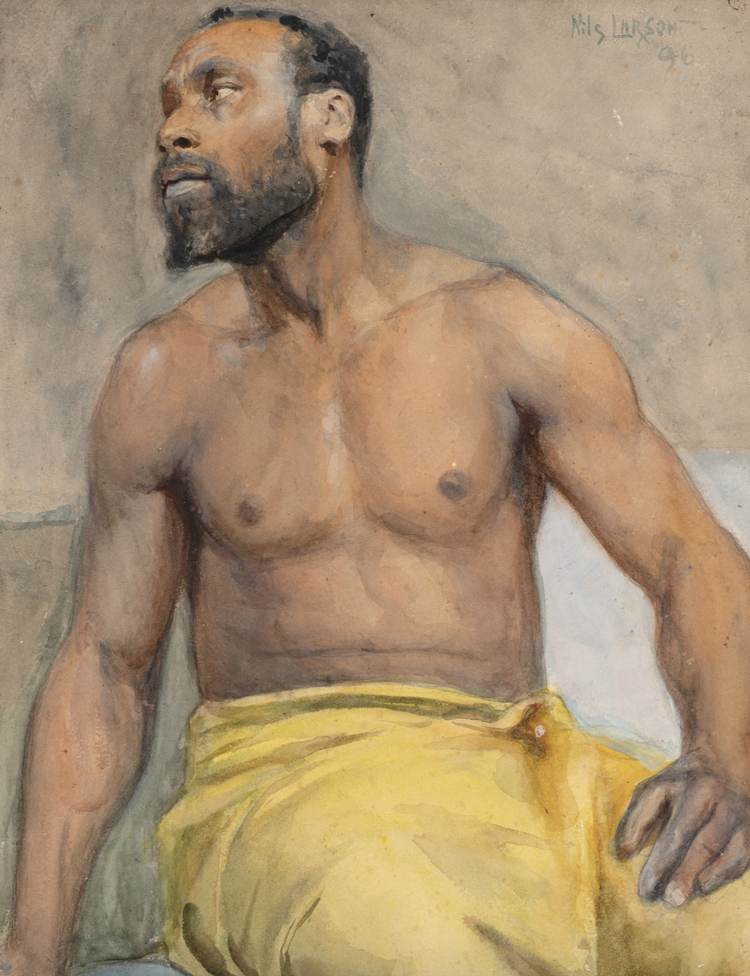

Nils Larson, A study of the model Pierre Louis Alexandre, 1896, watercolour on paper, 51 x 40 cm, High Museum of Art, Atlanta (Image: Elliott Fine Art)

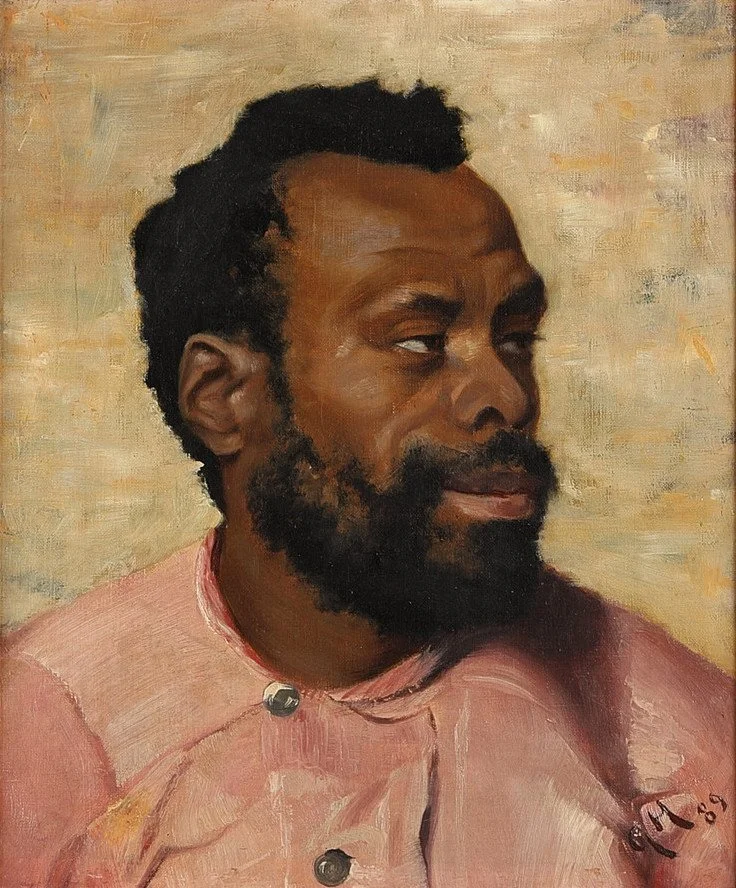

Georg Hansen, Petterson in profile, 1889, oil on canvas, 45 x 37 cm (Image: auctionnet)

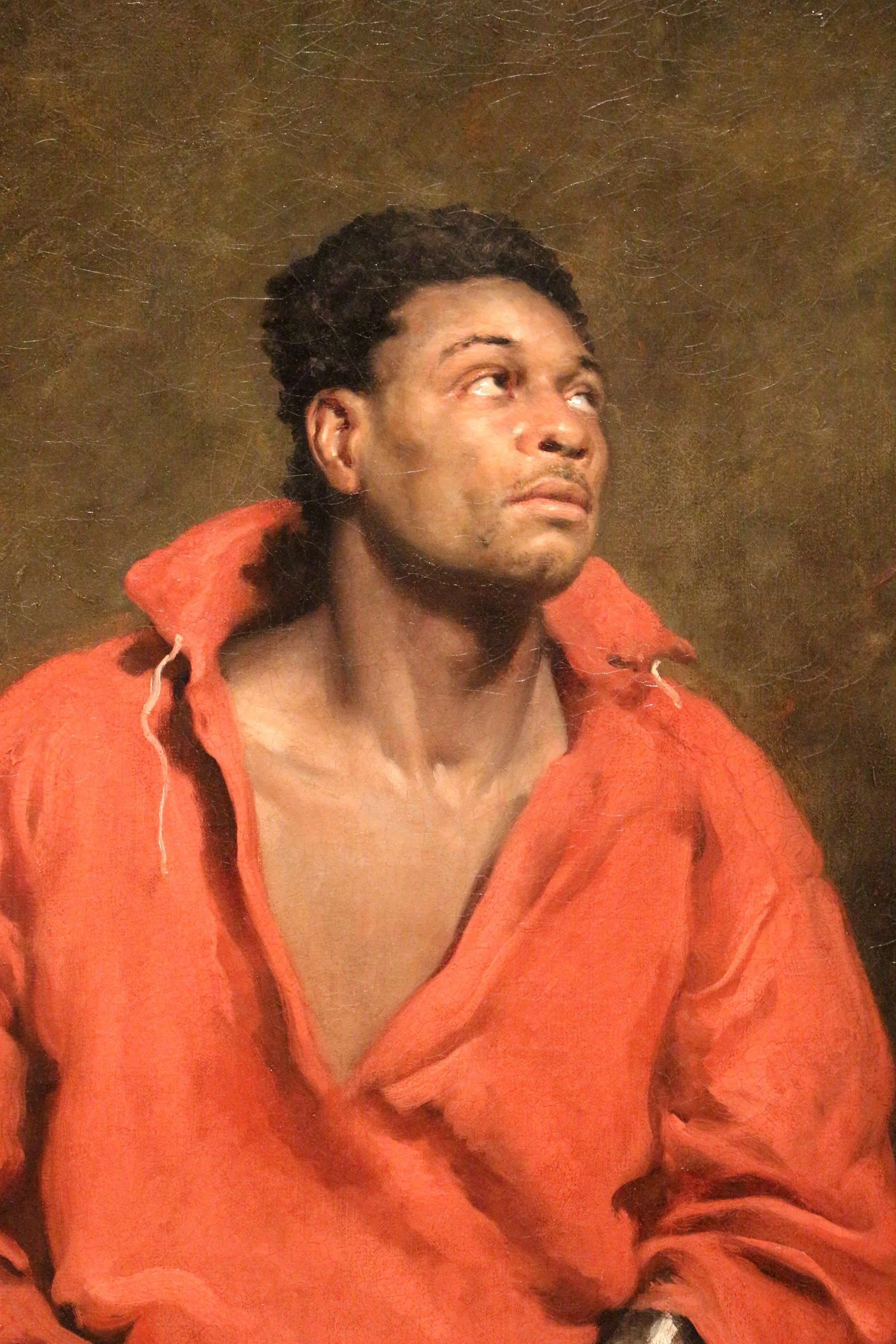

We recently finished our series of short videos about depictions of Black men in European paintings, from the 13th to 19th centuries. Although we see a huge range of paintings, possibly the most consistent theme over these 500 years is the fact that so many of the sitters remain anonymous; their identities have been historically excluded from records, and long overlooked by art historians. For example, the identity of the young boy in ‘Elihu Yale with Members of his Family and an Enslaved Child’ (painted in 1719 and attributed to John Verelst) has been investigated by researchers - however the baptismal, marriage or burial records in Camden, London, offer no clues. Instead, the sitters who are identifiable tend to be already well-known figures in society at the time - for example, Ira Aldridge (the American actor who was the first Black man to play Othello in 19th-century Britain) or Jean-Baptiste Belley (the Haitian politician who led an Infantry during the Haitian Revolution from 1791). Aldridge appears in other paintings as an artist’s model, such as in John Simpson’s ‘The Captive Slave’ - which, although intended to be a statement in support of the abolition of slavery, nonetheless continues to depict Blackness in relation to slavery and subjugation.

Attributed to John Verelst, Elihu Yale with Members of his Family and an Enslaved Child, c. 1719, oil on canvas, 201.3 x 235.6 cm, Yale Centre for British Art, New Haven (Image: Wikipedia)

John Simpson, Detail of The Captive Slave, 1827, oil on canvas, 127 x 101.5 cm, Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago (Image: Wikipedia)

The artist’s model Pierre Louis Alexandre is an exception in many ways. Firstly, there are around 40 surviving works in which Pierre is the model, dating from between 1878 to 1903 in Stockholm - which probably makes him the Black sitter about whom we have the most images in pre-20th-century art. In this article, we will explore a selection of these paintings, and how they could be interpreted as either challenging or reinforcing stereotypes of Black men in late 19th century Europe.

Pierre was probably born into slavery in French Guiana in 1843 or 1844. He managed to arrive in Stockholm in 1863, most likely as a stowaway on an American ship - a two to three month journey which would have required an immense amount of determination and strength. Once in Stockholm, Pierre found work as a dock labourer but soon became an artist’s model at the Academy of Fine Arts. According to archival evidence, Pierre married twice (having two children with his first wife), lived at several addresses over the years in Stockholm, and he died in his early sixties in 1905 of tuberculosis. The black presence in Sweden in the late 19th century would have been far less prominent than, for example, in Britain and France - and so Pierre seems to have been a well-known figure at the docks, as seen in depictions of him by the caricaturist Albert Engström in the early 1890s.

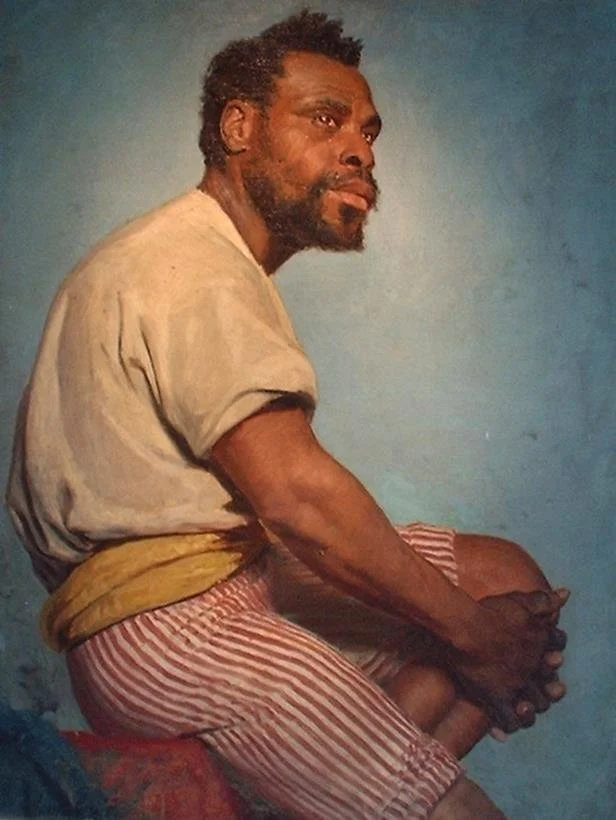

The best known portrait of Pierre is by painter and designer Karin Bergöö Larsson. She made this painting around 1879 during her time at the Royal Swedish Academy of Arts (where she studied from 1877 to 1882). Bergöö Larsson was married to another prominent Swedish painter Carl Larsson. Professor Monica L. Miller offers a closer look at this portrait: “Although [Bergöö Larsson] seemingly includes an element of the ‘Moor’s’ costume (the sash), she transforms it into the uniform of a sailor or a denizen of the docks, which was [Pierre’s] occupation, marrying it to the red-striped pants and rolling his shirt sleeves… [This is] a study of his quiet strength, possible only through, one supposes, a palpable sympathy between sitter and artist.” We could also note that Bergöö Larsson was the main model for her husband’s paintings, which possibly gave her a greater understanding of what it was like to be in front of the artist’s canvas.

Karin Bergöö Larsson, Negern Pettersson, c. 1879, oil on canvas, private collection (Image: Female Artists In History)

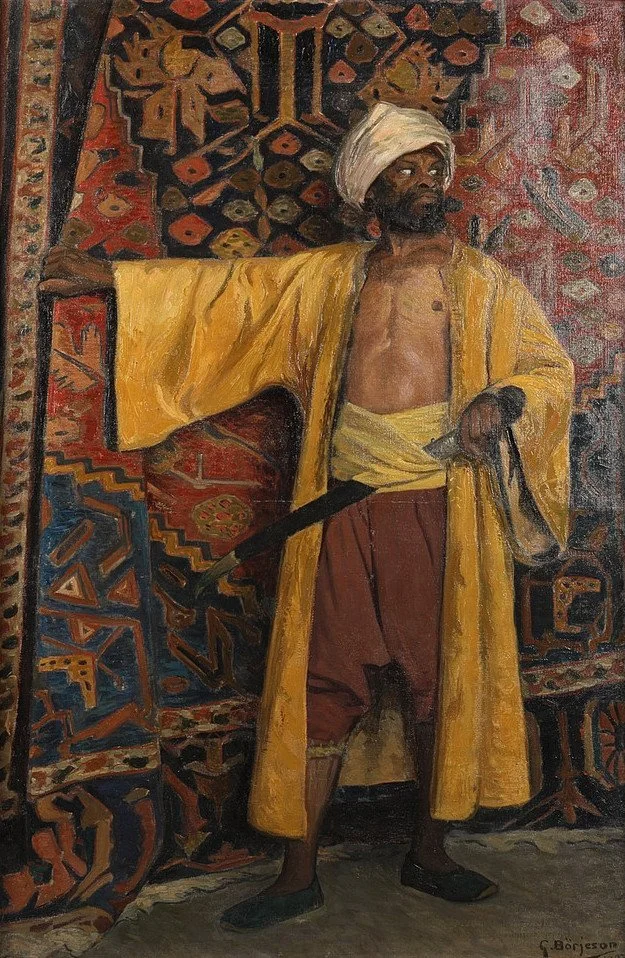

Gunnar Börjeson, Petterson, 1903, oil on canvas, 161. 5 x 106 cm (Image: auctionnet)

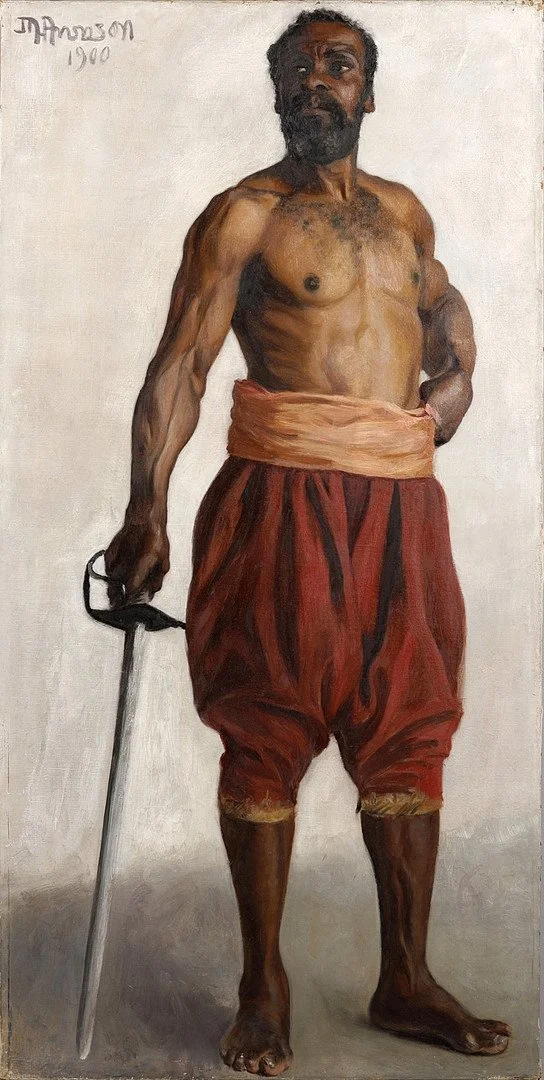

Martin Aronson-Liljegral, Petterson, 1900, oil on canvas, 140 x 69 cm (Image: auctionnet)

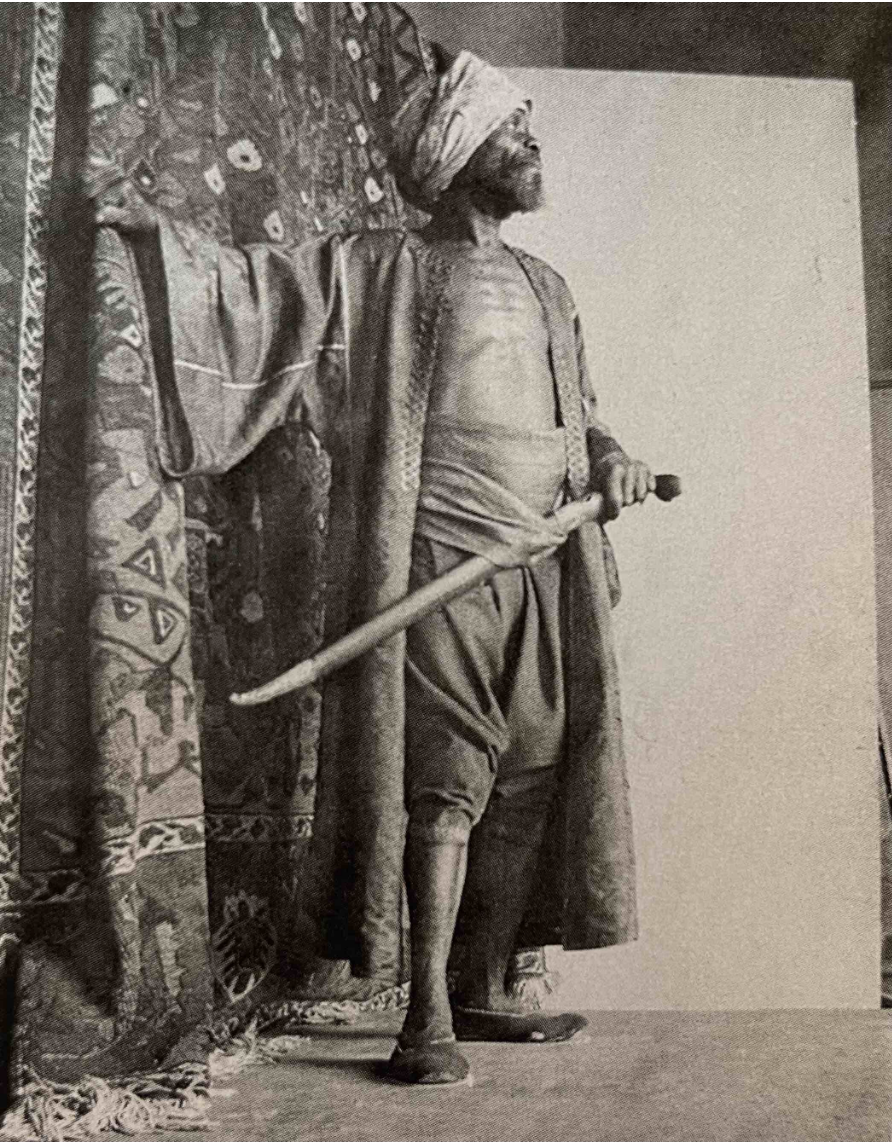

In many paintings, Pierre has been depicted in the costume of a ‘Moor’, such as in the painting by Gunnar Börjeson (made in 1903), in which he wears a turban, sash and sword. Börjeson treats Pierre not as an individual, but simply as a model with darker skin, used to explore a Western ideal of the Orient (regardless of the fact that Pierre was not from Asian or Arab cultures). This exoticising treatment of a Black model is typical of many historical depictions: we might think of Dutch painter Gerrit Dou’s ‘Head of a Boy in Turban’ (c. 1635) or ‘Portrait of a Young Black Italian Man’ by Alessandro Longhi (c. 1760s).

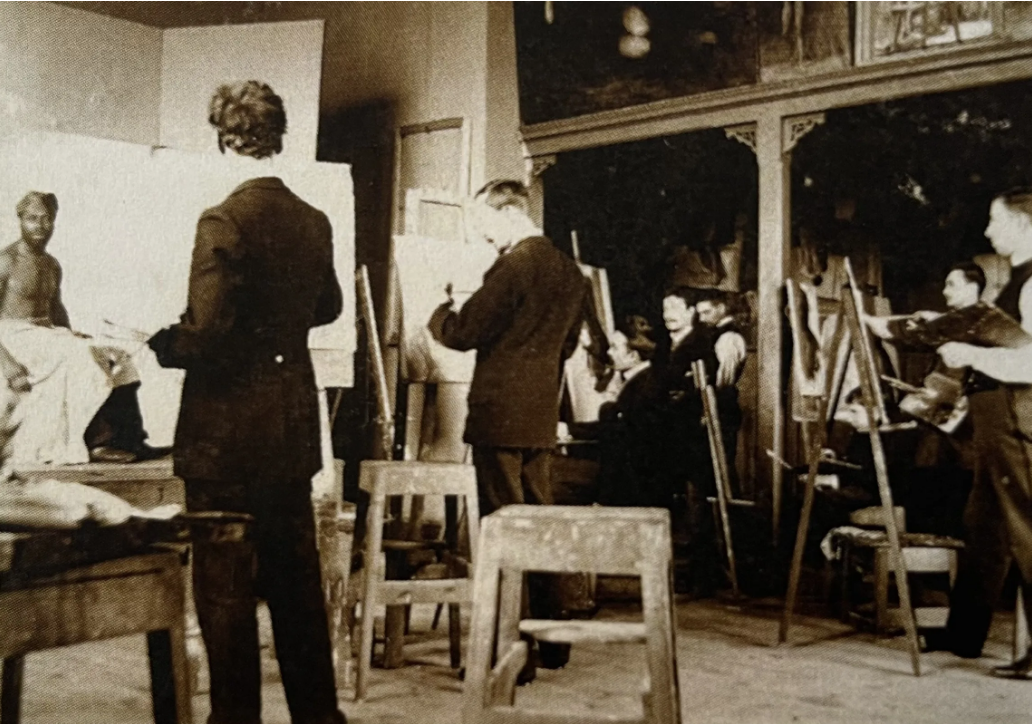

Pierre is also depicted by the relatively unknown artist Martin Aronson-Liljegral, who was born in Blekinge in 1869. Although Pierre is represented in an imposing, almost noble stance with his hand on his hip and head held high, it is important to note that the visual focus on his muscularity and athleticism could be seen as a reflection of the historical tendency to value Black bodies according to their physical strength (as well as to emphasise the subjects’ sexuality above all else). The same could be said for Nil Larsson’s watercolour study of Pierre, made in 1896 during a life drawing class at the Royal Swedish Academy of Fine Arts in Stockholm. At the same time, there is a humanity and tenderness in this watercolour, in particular.

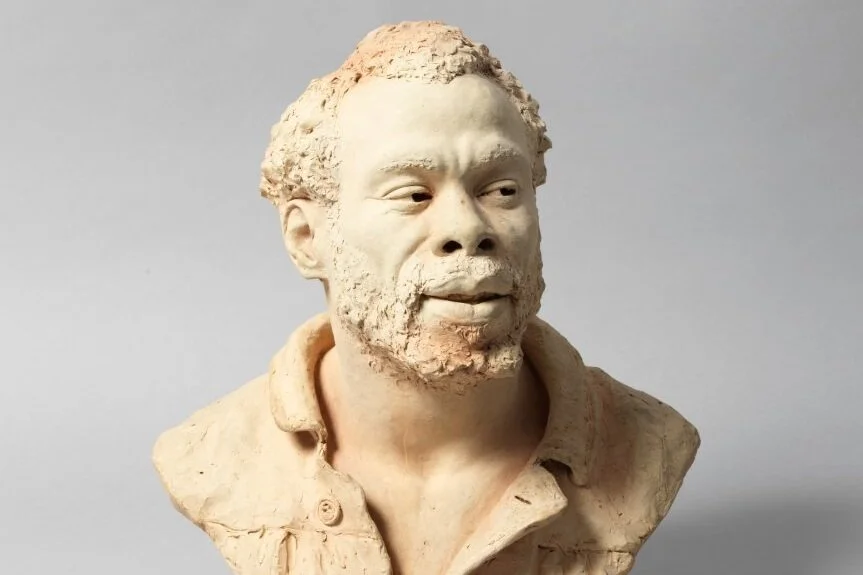

Verner Åkerman, Pierre Louis Alexandre, 1885, terracotta, 43 x 36.5 x 24 cm, Nationalmuseum, Stockholm (Image: Nationalmuseum)

Despite many of these depictions presenting a sense of sympathy between sitter and artist, it is significant that Pierre was often referred to with the derogatory term ‘Negern Pettersson’. Professor Miller notes that Pierre’s “presence in the Royal Academy’s atelier was initially designed as an academic exercise, an opportunity for Sweden’s artistic elite to draw or paint a främling, or stranger, a man with dark skin, wooly hair, fuller lips.” We can arguably see an example of this in the terracotta bust of Pierre made by sculptor Verner Åkerman in 1885. The Nationalmuseum in Stockholm describes the sculpture as “not a portrait in the strict sense but [rather] a so-called "character head", a genre that was cultivated in academy teaching.” This interest in types of heads was not only found in artistic institutions, but also in 19th-century scientific rhetoric (we might think of the racist pseudoscience of Dr. Samuel Morton and the so-called slave daguerreotypes of Louis Agassiz). Just a year later, Åkerman’s sculpture was shown in an exhibition under the title ‘Zambo’. This seems to not only exemplify how entrenched the exoticising (or ‘othering’) approach to Black sitters at the time, but also how readily Pierre’s identity was erased by the art world (even despite being depicted in the working shirt of a dock labourer).

Depictions of Pierre Louis Alexandre remind us of the complexities in historical representation of Black people in art history, an area which is rightly being given increasing attention by both art historians and art lovers. They also remind us of how many contradictions and nuances can co-exist within one artwork.

Two photographs of Pierre Louis Alexandre modelling in life classes at the Royal Swedish Academy. From High Museum of Art, Atlanta (Image: Elliott Fine Art)

(Written by Esme Garlake on behalf of Athena Art Foundation, April 2022)