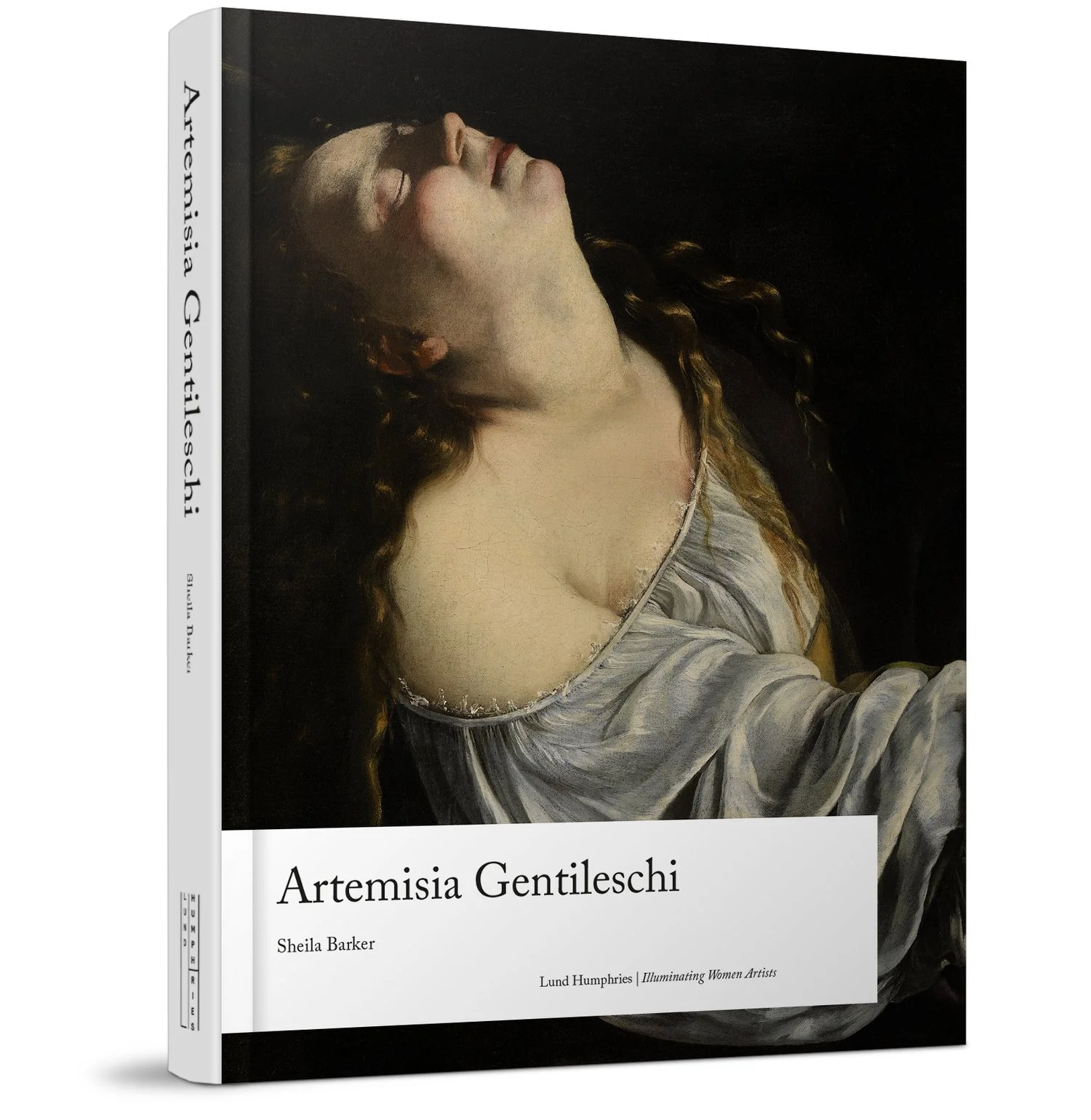

Artemisia Gentileschi: March Pick of the Month

Artemisia Gentileschi, Judith and Her Maidservant with the Head of Holofernes, c.1624-7, oil on canvas, 187.2 x 142 cm, Courtesy of Detroit Institute of Arts

TW: sexual assault

To mark the celebration of Women’s History Month, we are reflecting on the remarkable life of Italian Baroque painter, Artemisia Gentileschi, with two exclusive extracts from Sheila Barker’s new book for Lund Humphries’ Illuminating Women Artists series. Artemisia is one of few women from the 17th century who managed to pursue a career as a painter, and she is now acknowledged as one of the finest painters of all time. Although she employed models, she often used her own likeness on her female figures, creating a fascinating tension between art and life. She is best known for her psychologically insightful portrayals of courageous women struggling against adversity.

Artemisia was born in Rome in 1593 and was mainly brought up by her father, Orazio Gentileschi (her mother died in 1605). Her father was an established painter from Pisa, whose style was heavily influenced by Caravaggio’s realistic and psychologically powerful paintings. Artemisia trained alongside her three younger brothers in her father’s workshop, and by the time she was seventeen years old, she was already known in the city for her artistic talent. Artemisia’s earliest surviving painting is Susanna and the Elders (painted in 1610) clearly shows Caravaggio’s influence, as well as that of Annibale Carracci’s classicism.

Artemisia Gentileschi, Susanna and the Elders, c. 1610, oil on canvas, 170 x 119 cm, Schloss Weißenstein, Germany (Image: Wikipedia)

Artemisia Gentileschi, Judith Beheading Holofernes, c. 1612-13, oil on canvas, 158.8 x 125.5 cm, Museo Capodimonte, Naples (Image: Wikipedia)

The event in Artemisia’s life which has been given much attention by art historians, particularly in recent years, has been the story of her rape - when she was seventeen - by the painter Agostino Tassi. Although Tassi was taken to court and found guilty, his punishment was not enforced; by contrast, Artemisia suffered brutal slander and even torture at the trial. In many of Artemisia’s paintings, we see scenes of extreme violence carried out by a strong heroine, such as Judith Beheading Holofernes, for example. Some have seen these paintings as the result of the artist’s experiences as a victim of violence. This reductive view of Artemisia’s painterly genius and international success is no longer convincing. As the singer FKA Twigs pointed out in a video dedicated to a close analysis Judith Beheading Holofernes in 2020: ‘why should a woman’s entire body of work and identity be defined by her sexual assault?’ Indeed, there are many other experiences which shaped Artemisia’s life and works.

Following the trial in 1612, Artemisia moved to Florence, where she married a modest Florentine apothecary with whom she would have five children, four of which died in infancy. In 1516 in Florence, she joined the Artists’ Academy and was the favourite painter of the Medici Grand Dukes. Upon returning to Rome in 1620, Artemisia was a very popular artist, commissioned by noblemen, princes and cardinals. She was known for her large-scale depictions of historical and biblical themes inspired by the great male artists of her era, such as Caravaggio, Peter Paul Rubens and Guido Reni. In the final 25 years of her life, Artemisia worked in Naples, where she ran her own successful workshop. Between 1638-40, she even worked for the King of England in London, where her father had worked as a court painter until his death1639.

Sheila Barker’s new book explores how Artemisia was able to achieve such a lucrative and high-profile career in an era when the odds were stacked against the success of a female painter. Using recent archival discoveries and newly attributed paintings, Barker clears a pathway for non-specialist audiences to appreciate Artemisia’s artistic intelligence.

Sheila Barker is an art historian and writer. She is the founding director of the Jane Fortune Research Program on Women Artists at the Medici Archive Project. Her publications include the exhibition catalogue The Immensity of the Universe in the Art of Giovanna Garzoni as well as the edited volumes Artemisia Gentileschi in a Changing Light, Women Artists in Early Modern Italy, and Artiste nel chiostro (co-edited with Luciano Cinelli).

(Written by Esme Garlake on behalf of Athena Art Foundation, March 2022)