Women's History Month: Evelyn De Morgan

To celebrate Women’s History Month, we are collaborating with The De Morgan Museum to learn more about 19th-century English painter Evelyn De Morgan. The De Morgan Museum is a public gallery in Barnsley, Yorkshire which holds the paintings, ceramics and artworks created by Evelyn De Morgan and her husband William De Morgan. On 23 March at 7pm we will be hosting a free online event in conversation with the Museum’s director Sarah Hardy, to learn more about their new exhibition Evelyn De Morgan: The Gold Drawings (opening on 11th March at Leighton House in London).

The following text is edited from the De Morgan Foundation

Who was Evelyn De Morgan?

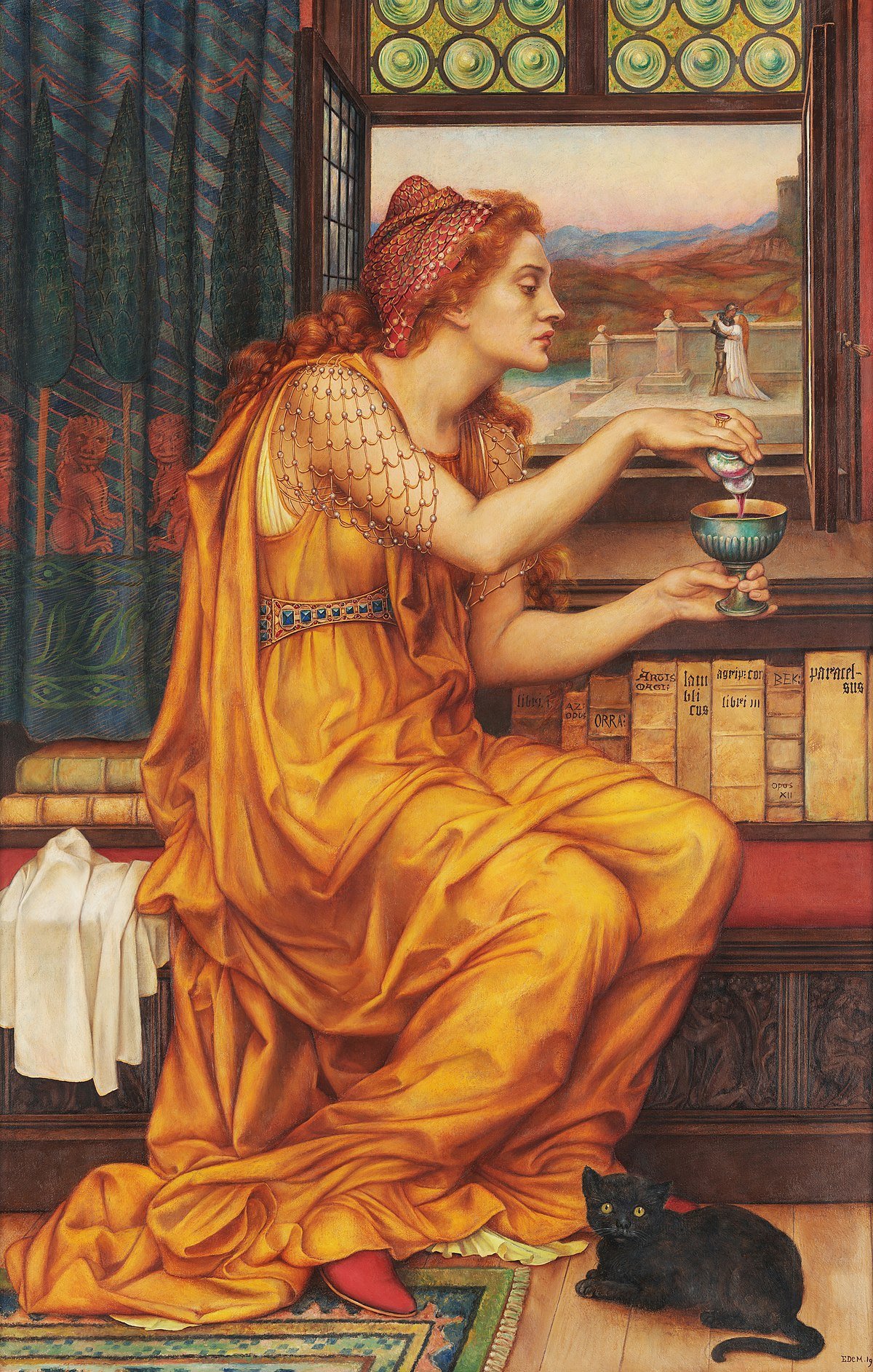

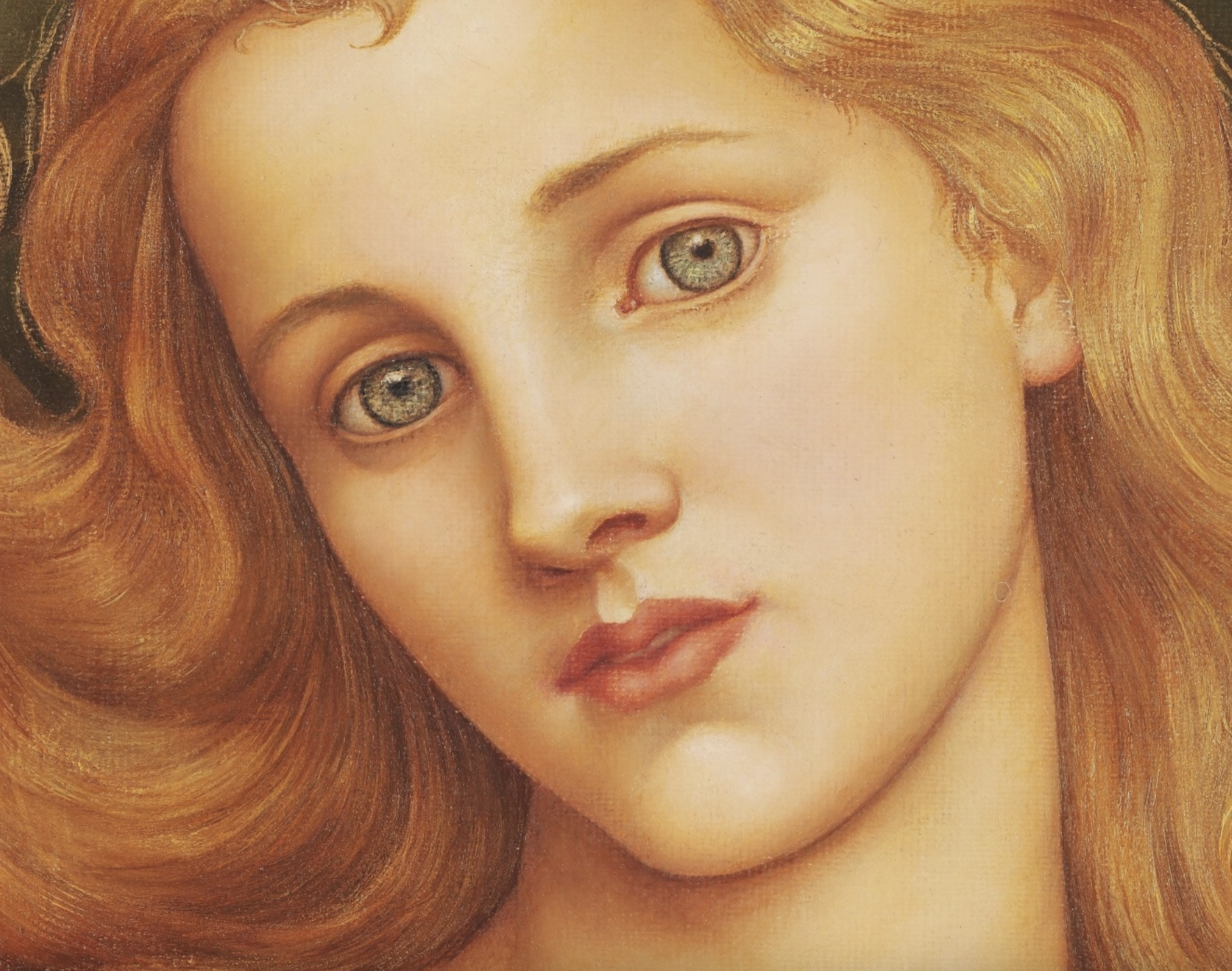

Evelyn De Morgan (1855-1919) was a painter who defied the expectations of her class and gender to become one of the most impressive artists of a generation. Her richly coloured canvases featuring beautifully draped figures, deliver messages of feminism, spirituality and the rejection of war and material wealth, making them incredibly relevant today.

Early life

Image: The De Morgan Foundation

Evelyn was born in 1855 in London to upper-class parents Percival Pickering Q.C. and Anna Maria Spencer Stanhope. The family was a notable one, through a line of politicians and Yorkshire landowners on her father’s side and from nobility on her mother’s, who were direct descendants of ‘Coke of Norfolk’, Earl of Leicester.

Evelyn was educated at home by tutors, in keeping with an appropriate middle-class upbringing. She was taught with her brothers, meaning that her lessons were in Latin, Greek, French, German and Italian, as well as classical literature, mythology and the sciences, subjects rarely available to girls of her age. Religion also played a huge part in the Pickering children’s education, taught by pastors who visited the house with the same regularity as the tutors.

The De Morgan Foundation owns a collection of Evelyn De Morgan’s juvenile poetry, written between the ages of 13 and 15. It is interesting to note that, from this young age, Evelyn used her art as a tool to express her socialist, spiritualist and feminist values which would become key themes in her later paintings.

In her biography of Evelyn De Morgan, the artist’s younger sister Wilhelmina Stirling reports that her parents rejected Evelyn’s wish to become a painter. She claims their mother remarked that she wanted a “daughter, not an artist” and reports that she would tip the drawing tutor to tell Evelyn that she was no good, in the hope that she might give up on her dream. As an unmarried woman, Evelyn would have relied on her father’s support as, by law, she was unable to own her own money or property. His diary is preserved in The De Morgan Foundation’s archive and suggests that he did support her ambition, as he began paying for his eldest daughter to have private drawing lessons with a tutor named Green in the 1870s and allowed her to travel accompanied by her artist uncle to France and Italy to study from Old Master paintings. Without this support, she would not have had the means to pursue her career.

Artistic training

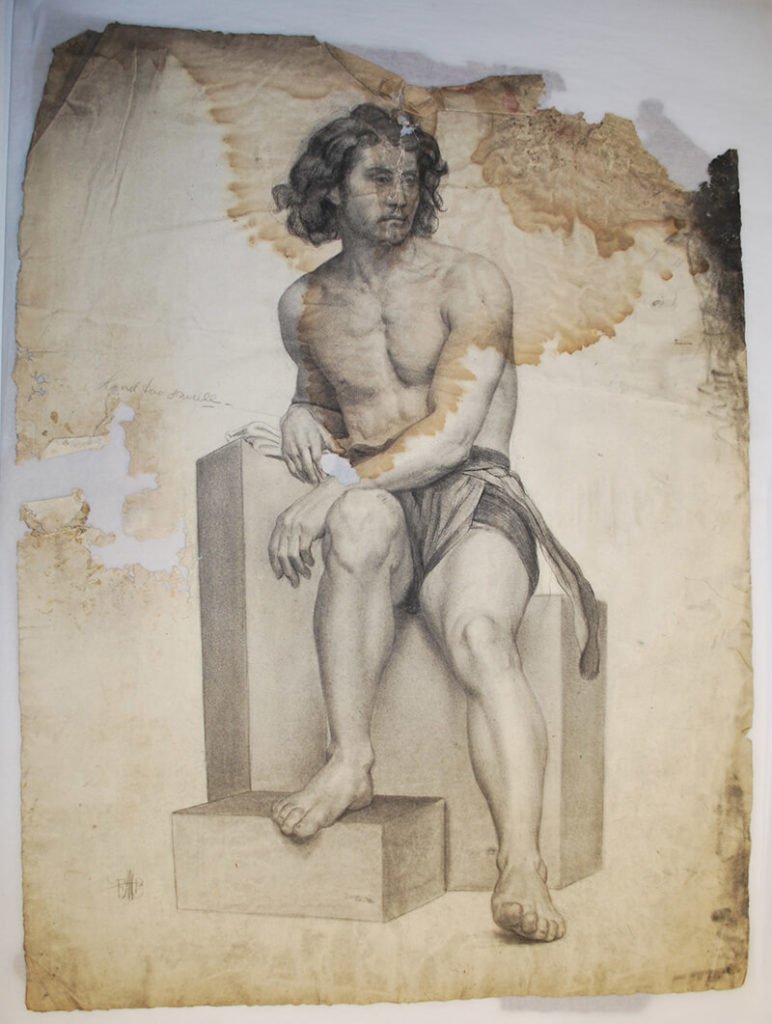

In 1872, Evelyn spent some months studying at the South Kensington National Art Training School, but her aspirations were clearly at odds with the school’s traditional emphasis on the more feminine idea of artisanship and ‘accomplishment’. The next year she enrolled at the newly established Slade School of Art, becoming one of the first women to do so.

The Slade School of Art was established by lawyer and art collector Felix Slade at the University College London. The 1873 – 1874 syllabus reveals that Evelyn would have taken classes each day in drawing from the draped and nude model for four hours and from the antique model for a further three. Allowing female students to study from life alongside their male colleagues was revolutionary in art education for the time and the importance of this as a move forward for the art world cannot be overstated. Although revolutionary, it was still a taboo idea and so women studying after 5pm were banned from drawing from nude models.

Once she had graduated from the Slade School of Art, Evelyn continued to draw every day for the rest of her life. Her drawings are enlightening not only for their skill and subject matter, but also because they help us to understand her working process. From loose compositional sketches, Evelyn swiftly progressed to detailed life studies for the figures in her paintings. Choosing to draw mainly on a grey wove paper in pencil and pastel, Evelyn produced hundreds of figure studies. Her rigorously-examined double studies of clothed and nude figures are particularly fascinating and underline the artist’s obsession with the human form and her desire for accuracy.

Evelyn also produced exquisite drawings of details, such as faces, which were typically beautiful and characterful. Hands and feet were also studied at length to ensure realism. As a final element to her working process, Evelyn executed detailed compositional studies. These pieces can be considered works of art in their own right and it is apparent that Evelyn often sold them as such. The works in gold on dark grey wove paper are of particular interest, as very few artists used this technique, although it is known that Edward Burne-Jones produced similar works. The high contrast between the grey of the paper and the bright gold allowed Evelyn to ensure that her pictures would have a rich tonal depth, perfect lighting and enviable realism.

Early career

At the Slade School of Art, Evelyn had been a pupil of Sir Edward Poynter, who later became the President of the Royal Academy of Arts. Poynter painted in the popular Aesthetic style, a movement of fine and decorative arts which sought to deliver beauty above meaning, or to create ‘art for art’s sake’. This movement borrowed classical style and Renaissance motifs, the mystic and majesty of Botticelli’s art came to be particularly admired amongst the aesthetes. It was at the height of this movement’s popularity that Evelyn began exhibiting her work.

Ariadne at Naxos, 1877 (Image: De Morgan Foundation)

The first picture which Evelyn De Morgan exhibited was St Catherine of Alexandria (1875) at the Dudley Gallery in London, in 1876. From the outset, she would battle against the sexist attitudes of the art world and strive to be recognised for her skill, rather than her gender. This picture was successful at the exhibition, being purchased directly by Lord Henry Somerset, a Conservative MP. Following her success at the Dudley Gallery, Evelyn was invited to exhibit at the Grosvenor Gallery, a temple of avant-garde painting. In order to ensure the commercial viability of her pictures, Evelyn continued to work in the popular Aesthetic style and her first Grosvenor exhibit, Ariadne at Naxos (1877), is typical of her work during this period.

Although Evelyn maintained an allegiance to popular styles (ensuring that her pictures were fashionable to prospective patrons), she cared very little for the values of movements whose aesthetic qualities she borrowed. Instead, she sought to use her canvases to present her own socio-political concerns to a wider public and act as a catalyst for change. In her early pictures, this is more subtle, in order that her pictures could be recognised as Aesthetic. Certainly, with its desolate, dreamlike beach, richly draped female gazing away from view and limited palette, Ariadne is – stylistically – an Aesthetic work of art. However, the title of the work gives the picture narrative, which was against the Aesthetic code. Ariadne is depicted alone and abandoned on the island of Naxos, a point in Greek myth when she has been left by her lover Theseus, who is traditionally painted sailing off into the distance when artists tackle this theme. Evelyn has instead put the female character at the centre of the canvas and dressed her in the red robes of Christian martyrs, successfully yet subtly imbuing the painting with a subtext about female suffering and abandonment by the patriarchal society she lived in.

Evelyn was an artist who demonstrated sophisticated knowledge of the materials and methods involved in creating oil paintings. She generally used Roberson’s pre-stretched, double-lined canvases which have structural integrity, and Windsor and Newton oil paints, pigment bound in an oil medium, meaning that she didn’t need to prepare her canvases or mix her own paints. These modern methods mean that her pictures survive with beautiful clarity and excellent detail today.

Marriage

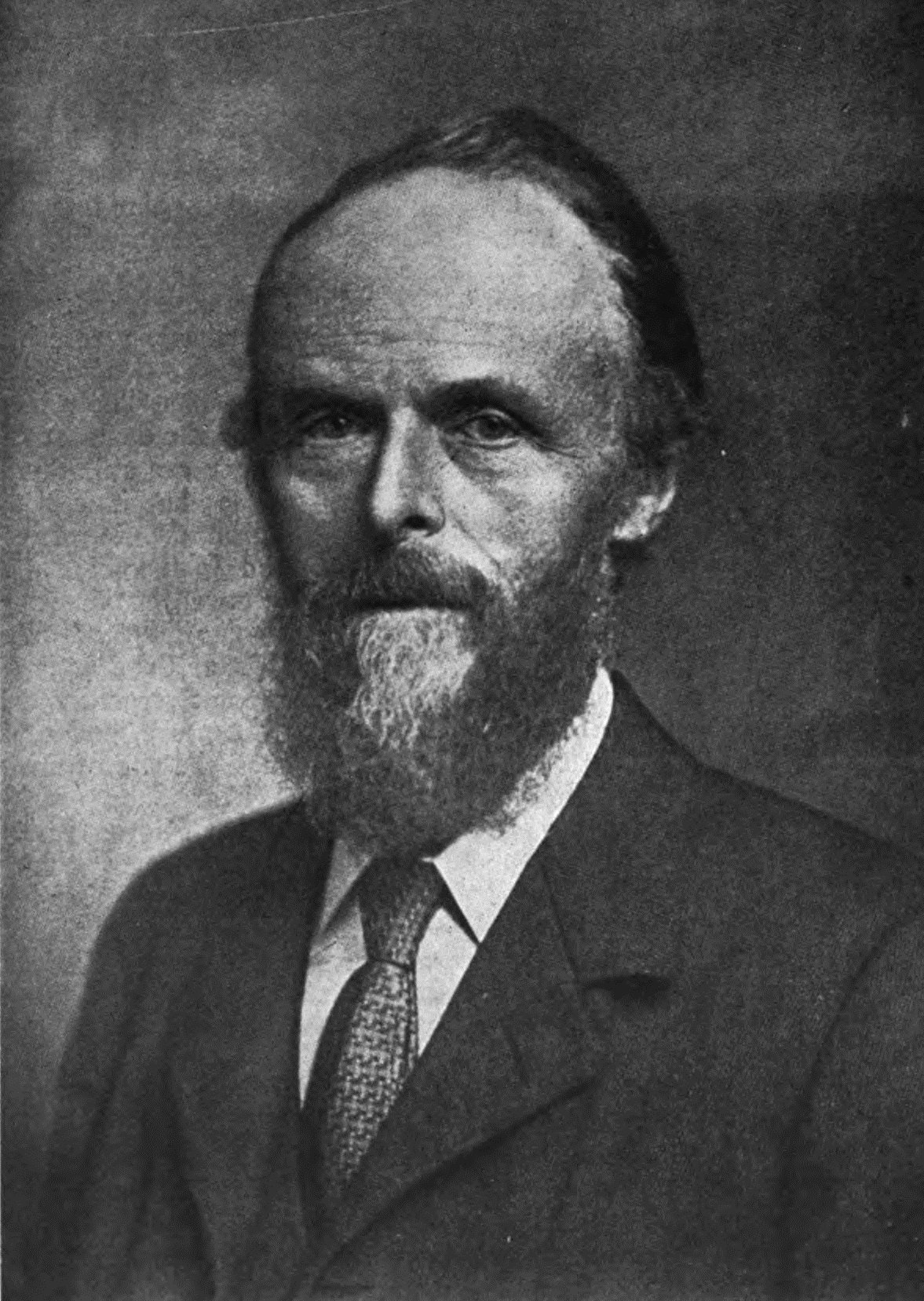

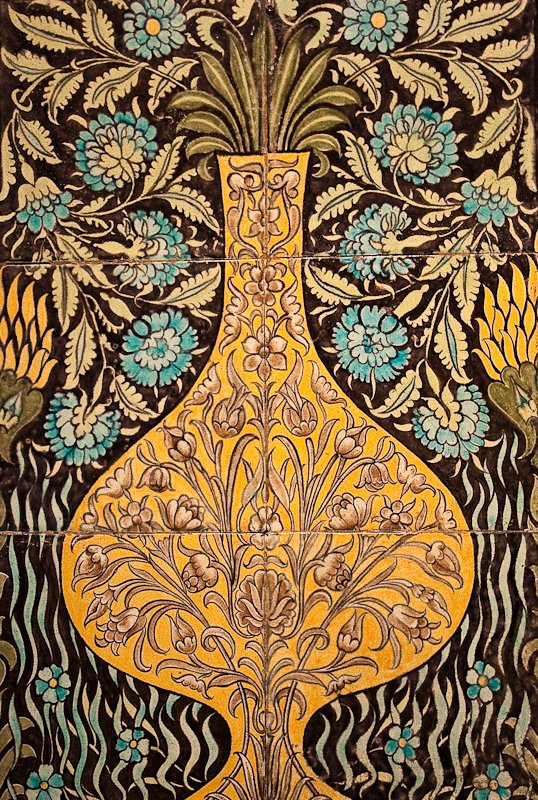

Undated archival photograph of Evelyn and William (Image: Delart.org)

In 1883, Evelyn met the Arts and Crafts ceramic designer, William De Morgan. He clearly had an impact on Evelyn and her artwork; love became an important theme after their meeting, particularly for her first allegorical work Love’s Passing (1883-4). Allegories are pictures full of symbols and code which must be read to reveal their meanings. Working in this way, Evelyn could shroud her deeply spiritual works and ensure that they remained popular when exhibited for sale. Open at the feet of the two young lovers, who are distracted whilst listening to love’s sweet music, is a verse from one of the ancient poets, Tibullus’s elegies. It tells of the sadness that the poet feels in imagining the passing of his lover in later life. Evelyn clearly related to this narrative after finding a true love who was 16 years her senior.

Since childhood, Evelyn had been preoccupied by the omnipresence of death in life. Her juvenile poetry reveals her early comprehension of the Christian doctrine of resurrection and her paintings present her later interest in Spiritualism and the nature and matter of the human soul. Through her marriage to William De Morgan, Evelyn was introduced to his mother, Sophia, who was a social reform campaigner and a practicing Spiritual medium. It appears that the affirmation of her world view by her mother-in-law encouraged Evelyn to use her pictures to present her spiritual ideals.

Patrons

It is likely that Evelyn’s covert presentation of her socio-political agenda in some of her pictures was a result of her need to satisfy the market and her patrons at the end of the 19th century. William’s constant failing to turn a profit with his ceramics business resulted in the pair relying on income from the sale of Evelyn’s pictures. William Imrie, a Scottish shipping magnate and owner of the White Star Line, which famously created the Titanic, was Evelyn’s most prolific patron. In total, he bought eight pictures from Evelyn and probably had a say in the style of picture he wished to purchase, given how similar the Imrie Collection works and how far from this style the artist diverts when painting to satisfy herself rather than her patrons.

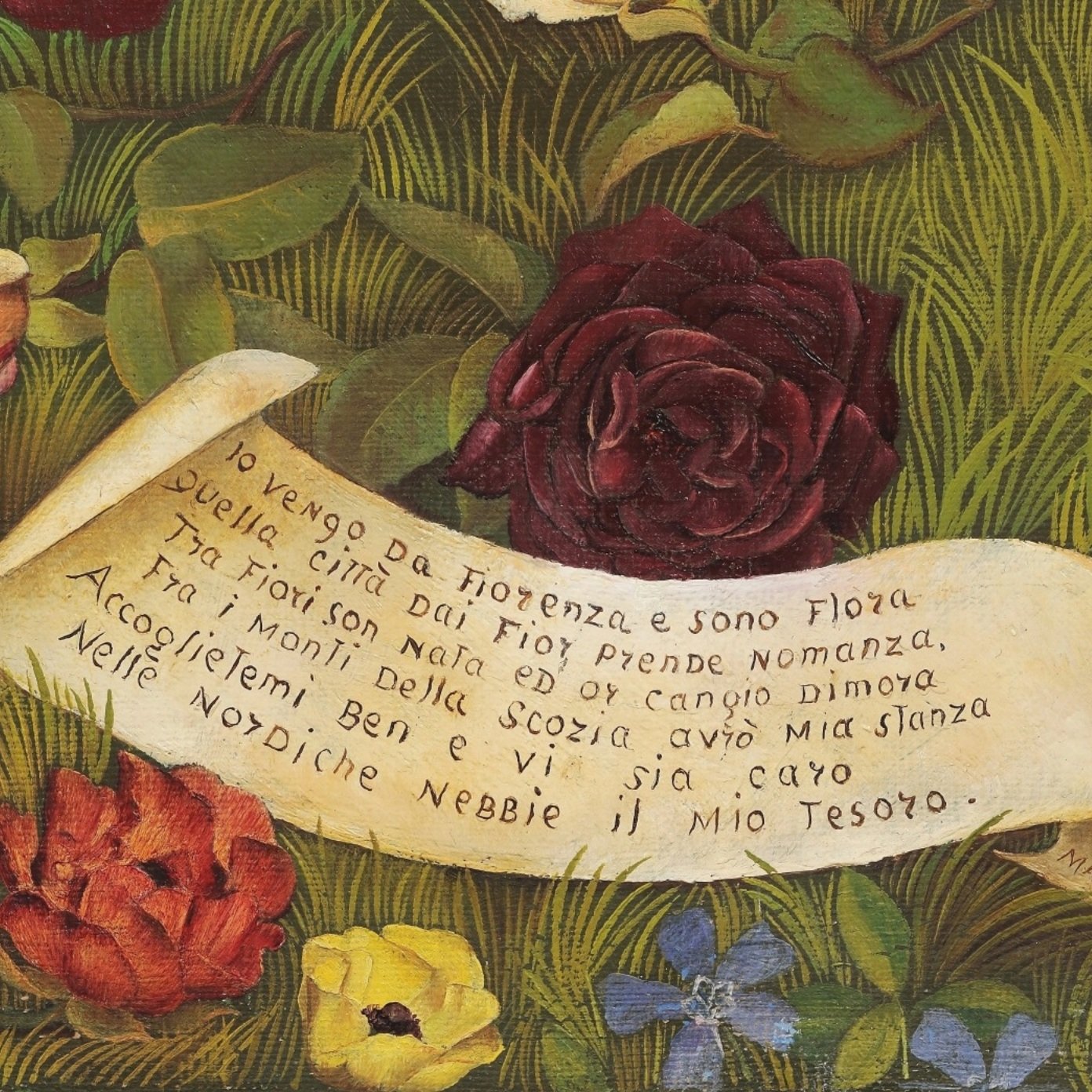

Flora (1894) is Evelyn’s most celebrated picture, which she painted for Imrie. The figure of Flora is based on Botticelli’s Primavera, but Evelyn has surrounded her with lush greenery, flowers, birds and swirling draped robes to make her iconic, instantly recognisable as Evelyn’s own. It is technically perfect, showing off her skill and mastery of the medium of painting in oils on canvas. The dazzling luminosity of the picture has been achieved by her innovative use of coloured oils over gold leaf, a method of her own invention, borrowed from medieval altar pieces found in the city of Florence, to which this picture is an ode. Flora is the goddess of springtime and of the city of Florence, where Evelyn lived during the winter from 1890 onwards. The scroll at the foot of the picture references Scotland, Imrie’s hometown, and so acknowledges the patron’s direction of the piece.

Later career

From around 1910, Evelyn’s colour palette moved from realistic and expressive to purely symbolic, as her pictures became more Symbolist in style. The Symbolists were a distinct group of French artists who had inspired Victorian painters in the 1870s and 1880s with their belief that paintings should be a gateway to spirituality. Evelyn’s interest in Symbolist painting came later in her career. William De Morgan’s successful second career as a bestselling author from 1907 meant that Evelyn was free to paint without limitations of commercial viability or the restraints of patrons.

Daughters of the Mist (c.1910) is a seminal piece in her Symbolist style. The swirls of rainbow mist show her new concern with colour to be symbolic, rather than to aid interpretation as it had in Cadence of Autumn (1905). Rainbows are synonymous with the coming of peace after the deluge in the Biblical story, and Evelyn interprets this as peace found by the soul at the end of the turbulence of life. The four female figures in this painting touch but do not interact. Their human form has been exploited to be purely expressive and the picture is devoid of direction or narrative. Instead, the viewer is invited to feel their spiritual awakening by interacting with the piece, so that the light may emanate from them, as it does for the topmost female in the picture.

Pacifism

Evelyn’s social consciousness is most notable in her pacifist paintings which she exhibited in her studio in 1916 to raise funds for the British Red Cross and the Italian Crocce Rosa. The outbreak of WWI and the horror of such barbarism and the enormous death toll this brought had a profound effect on Evelyn and her art work. Unable to imagine or faithfully portray the living hell faced by those serving on the front line, Evelyn used her Symbolist approach to paint demons and dragons to represent war.

S.O.S. (1914) depicts a gang of such beasts surrounding and bearing in on a tiny rock in a stormy sea, with a woman in a white robe reaching heavenward towards a rainbow. She represents the hope of peace for the isolated island of the UK in a world of war. The title, taken from the Morse Code for ‘save our souls’ suggests the imminent danger and want of rescue. Her pictures always focus on war as being an instrument of eventual peace, rather than in any way glorifying the reality of human suffering.

Evelyn died on 4th May 1919 and was laid to rest with her husband, William, at Brookwood Cemetery in Surrey. Over her 50-year career as a professional artist, Evelyn completed around 100 oil paintings, 56 of which are preserved in the De Morgan Foundation’s collection, along with an incredible collection of her preparatory drawings and sketches which demonstrate her talent, output and meticulous working method for creating such unique and beautiful pictures.

If you enjoyed learning about Evelyn De Morgan, and would like to find out more, please join us for an online talk and Q&A with the Director of The De Morgan Foundation on 23 March at 7pm.

Evelyn De Morgan, undated photograph (Image: Wikipedia)

(Edited by Esme Garlake on behalf of Athena Art Foundation, March 2023)