Can digital innovation help us learn about pre-modern art?

(Image: Gaëlle Mourre)

Recently, Athena Art Foundation was part of a panel discussion for Art History Festival 2022 about the project Living Portraits: Jem Belcher, which we produced in collaboration with the National Portrait Gallery, Megaverse and the National Youth Theatre. The project brought to life a portrait of 19th-century bare knuckle boxer James (Jem) Belcher, by combining digital innovation, theatre, art history and creative writing. This was the result:

The Q&A afterwards raised lots of fascinating questions about the use of digital technology in relation to historical artworks. We talked about the fact that, whilst digital intervention may not always appeal to everyone, the key is to offer new ways of appealing to wider audiences who may not have felt able to engage with pre-modern artworks before. Of course, cultural and heritage institutions are at the exciting early stages of experimenting with how digital innovation can enhance our understanding of art history, but there is also a lot to learn. It is fundamental that we never let the artworks themselves become overshadowed by technology. The ultimate aim of these projects is to encourage more people to go and see the paintings in real life, with a greater sense of confidence and engagement. We thought it would be interesting to look more closely at other recent projects which have focused on pre-modern art through different forms of digital innovation.

The Stolen Art Gallery (Image: PR Newswire)

A new Virtual Reality app (launched in July 2022) allowed users to experience five of the world’s most famous stolen paintings. The Stolen Art Gallery was created by the Brazilian company Compass UOL, and it features paintings by Caravaggio, Manet, Cezanne, Van Gogh and Rembrandt. The textures of the original paintings have been recreated with remarkable accuracy. Given that these paintings cannot be seen in real life anymore, digital technology clearly opens up alternative ways for us to experience artworks. It may hold answers in relation to questions of repatriation (museums can return artefacts and artworks and replace them whilst still offering visitors a chance to experience them as digital versions), or as a way of offering art enthusiasts a more environmentally responsible and financially viable option (cutting out the need to travel abroad to see paintings in real life which, for many people, is simply not possible). In a similar vein, the National Gallery’s exhibition Virtual Veronese (March-April 2022) allowed visitors to view the Italian painter’s ‘The Consecration of Saint Nicholas’ (commissioned in 1561) in a digital recreation of its original setting, as an altarpiece in the church of San Benedetto al Po, near Mantua, Italy.

Another recent Virtual Reality experience was available to visitors at the stately home Burghley House in Lincolnshire. The 14-minute immersive experience (Hi)story of a Painting: The Light in the Shadow transported visitors (via VR headsets) back to 17th-century Rome where the artist Artemisia Gentileschi was living and working. Produced by Fat Red Bird and co-created by Gaëlle Mourre (writer and director) and Quentin Darras (director and lead animator), the experience takes place in a room which is next to one of the treasures of Burghley House’s collection, Artemisia’s 1622 painting of Susannah and the Elders. Art critic Jonathan Jones described the experience: “it’s like being inside a graphic novel… VR is a time machine that can put you in a room in Rome centuries ago. And then you can travel for yourself, through the atmospheric corridors and staircases of this great old house, until you come across Susannah and the Elders, and suddenly time vanishes.” This example emphasises the power of storytelling for engaging audiences with pre-modern art; in a similar way that the script for Living Portraits: Jem Belcher was an essential part of the project, written by writer and director Edem Kelman.

Artemisia Gentileschi, Susannah and the Elders, 1622, oil on canvas, 161.5 x 123 cm, Burghley House, Lincolnshire (Image: Wikipedia)

(Image: Quentin Darras)

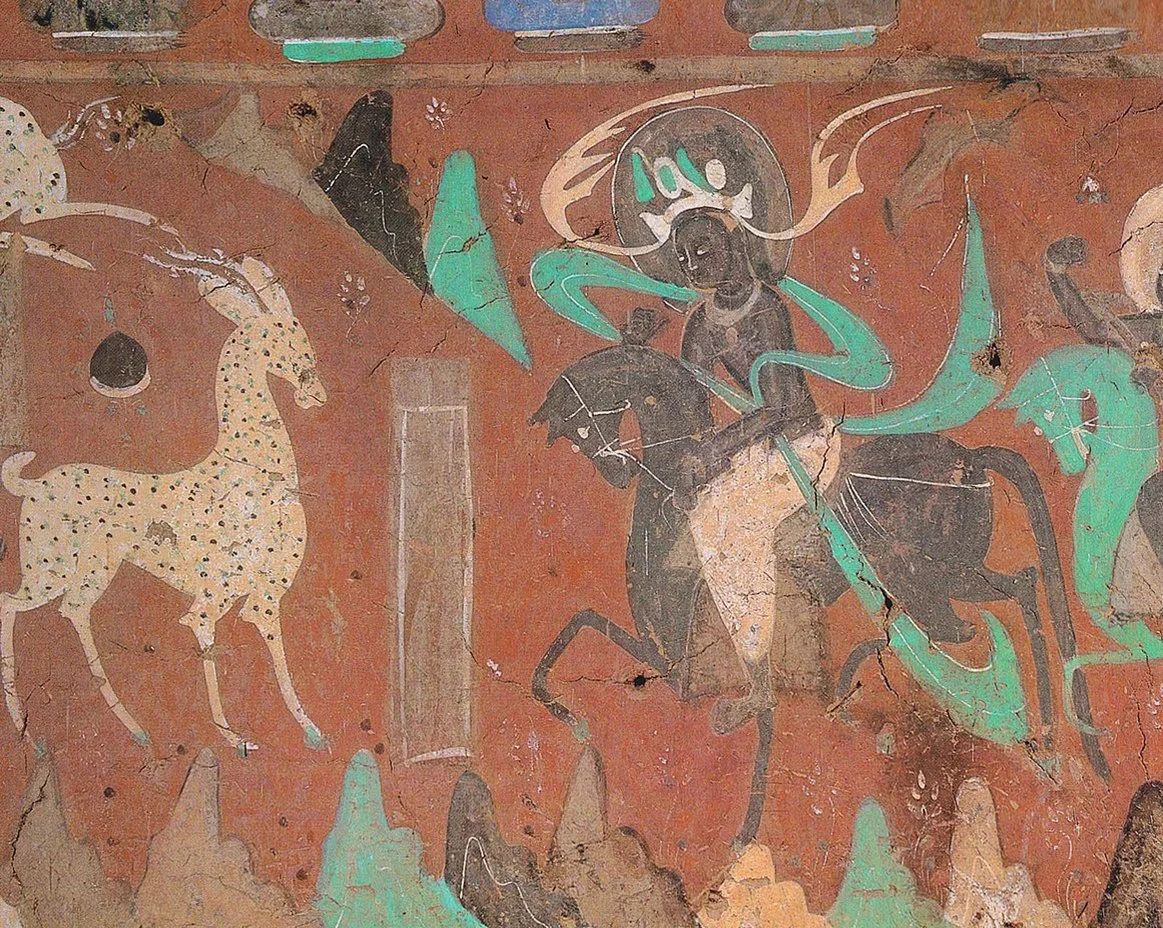

Video games are also providing new avenues for bringing cultural heritage sites to wider audiences. In August 2022, the mobile game Clash of Kings (reportedly played by over 300 million people worldwide) signed a landmark licensing agreement with the historic Chinese city of Dunhuang, giving exclusive access to the UNESCO World Heritage Site’s cultural IP. As Han Jing (co-founder of Artistory, the company which helped to broker the deal) explains, this new deal will allow “gamers to experience real, living history and culture” at a time when “we are seeing other museums and cultural institutions seeking opportunities in the gaming world”. By setting the game in Dunhuang, the site’s staggering archeological and artistic history will reach audiences from across the world. Dunhuang is found on the western edge of the Gobi Desert, and was once a Silk Road city which witnessed intense cultural, commercial and religious exchange along trade routes between the East and West. It is home to the Mogao caves, an ecosystem of 500 temples spanning 25km, which were decorated with elaborate Buddhist sculptures and paintings from the 4th century to the 14th century. Han Jing explains how players of the Clash of Kings “will experience something special and very authentic and close to what is seen on the cave walls”. The opportunities for gaming as a form of both entertainment and education is exciting. As the scholar Tine Rassalle writes, the combination of video games and archeology “completely immerses the player in historical information, but… in a nonlinear form, in which the player gets to pick and choose what she wants to spend time on.”

Most recently, a new multi-dimensional art experience called Frameless has just opened in a 30,000 square foot venue in central London. It promises: “you won’t simply be looking at a picture, you’ll be in the picture, with every brush stroke, every splash of colour, every moment of inspiration.” It includes four different galleries, with over 479 million pixels delivered by a million lumens of light, and a mixed contemporary and classical musical score played over 158 state-of-the-art surround sound speakers. Although such an experience is highly captivating, some visitors may feel that it moves too far away from the original artworks, and possibly places more emphasis on technology rather than the paintings themselves. Of course, if it encourages more people to go and see the paintings in real life, then these digitally innovative project have an undoubtedly important role to play.

(Image: Marble Arch London)

Let us know what you think via our Instagram @athenaartfoundation

(Written by Esme Garlake on behalf of Athena Art Foundation, October 2022)