Recreating Black Portraits: October Pick of the Month

October is Black History Month, and to celebrate we will be exploring a selection of Black artists and photographers who have recreated famous paintings as part of their work.

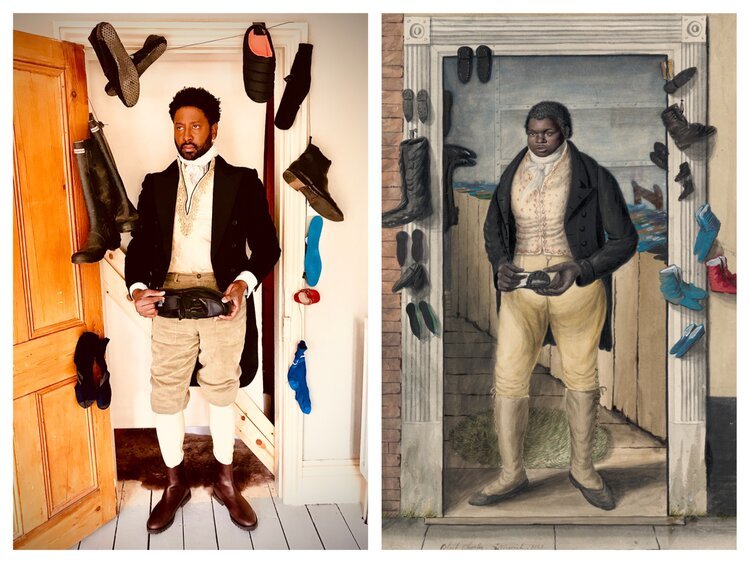

Peter Brathwaite recreates Hendrick Heerschop, The African King Caspar, 1654/1659, Gemäldegalerie der Staatliche Museen zu Berlin (Image: museumcrush)

During the Covid-19 pandemic lockdowns, an online craze saw many people recreating famous paintings in photographs, often with ordinary household items as props: toilet paper rolls stood in for ruffs, lampshades for umbrellas, or even dogs for baby Jesus. These recreations seem to offer a unique way of looking back at the paintings themselves, as we notice the - often overlooked - details. There is also a thrilling immediacy available through photography, holding up a contemporary mirror to pre-modern paintings. Yet recreating paintings goes far beyond a lockdown pastime: it is a practice which presents huge possibilities for exploring ideas of representation and identity.

Peter Brathwaite, an opera singer by trade, offers a brilliant example of this. Starting in lockdown, his series of photographs (in which he posed as Black figures in artworks from the 11th century to the present day) has developed into a remarkable body of work, Rediscovering Black Portraiture, fifty of which are due to be published in an upcoming book in 2023. The photographs were also displayed at his solo exhibition Visible Skin: Rediscovering the Renaissance through Black Portraiture which was shown at King’s College London’s Strand campus from October 2021 to February 2022. Brathwaite’s photographs are often playful and ingenious; others more solemn and pensive, but always with an attention to detail which shines a light on the original painting. The range of paintings which Brathwaite recreates also offers viewers a broad and rich selection of Black portraiture - and the presence of its sitters throughout history - which has for so long been left out of the history books.

In contrast to the homemade charm of Brathwaite’s photographs, the photographic recreations by Senegalese photographer Omar Victor Diop speak to the heritage of elaborate studio photography in Africa. In his 2014 series, Project Diaspora, he recreated twelve portraits in which he poses as notable Black people from history, between the 15-19th centuries. On his website, his project is introduced as being “a journey through time… [which] delves into and exposes less spoken narratives of the role of Africans out of Africa.” In one interview, he explains how he wanted “to look at these historical Black figures who did not fulfil the usual expectations of the African diaspora insofar as they were educated, stylish and confident, even if some of them were owned by white people and treated as the exotic other.”

Among the portraits recreated by Diop, there is Jean-Baptiste Belley, a Saint Dominican and French politician, painted by Girodet in 1797. Born in Senegal, Belley was a former slave from Saint-Domingue in the French West Indies who bought his freedom with his savings. Diop’s recreation shares the upward gaze and relaxed pose against a column, but adapts many details: the photographer excludes the bust of philosopher Guillaume-Thomas Raynal (a supporter of the abolition of slavery who had just died at the time Belley was painted), and inserts a football under his arm.

Football motifs are frequently recurring in Diop’s Project Diaspora, drawing parallels between modern day footballers in Europe and the men in the original paintings. We see this, for example, in his recreation of William Hoare’s 1733 portrait of Ayuba Suleiman Diallo (author of one of the earliest slave narratives), in which Diop photographs himself holding a red and white football. In Juan de Pareja (the Spanish painter depicted by Diego Velazquez around 1650), he holds football boots; in St Benedict of Palermo he holds a golden football (replacing the open book depicted in the original 18th-century statue). These strikingly contemporary objects present modern-day audiences with immediately recognisable connotations of fame and wealth which, arguably, encourages us to revisit the original paintings to search for any equivalent objects. Yet, as Diop explains in one interview, football is also “an interesting global phenomenon that… often reveals where society is in terms of race. When you look at the way that the African soccer royalty is perceived in Europe, there is a very interesting blend of glory, hero-worship and exclusion. Every so often, you get racist chants or banana skins thrown on the pitch and the whole illusion of integration is shattered in the most brutal way. It’s that kind of paradox I am investigating in the work.”

Although this project marks the first time that Diop has put himself in front of the camera, he is not comfortable with the photographs in Project Diaspora being called self-portraits. Instead, he explains, “they are metaphorical portraits in which the idea of black identity is central”.

By contrast, for Lola Wallace, a British photographer, the idea of self-portrait held significant implications when recreating ‘Portrait of Madeleine’ (painted by Marie-Guillemine Benoist in 1800), featured in the virtual exhibition Reimagine in 2021. The fact that Wallace’s recreation is also presented as a self-portrait allows her to reimagine the painting and “to recreate the power of Madeleine”. In the original painting, Madeleine is depicted with her breast exposed; a trope which reinforces racist narratives of Black women as sexualised objects of desire. Significantly, Wallace chooses to pose with her chest covered, “redressing [Madeleine] to return her ownership of dignity”. Again, by looking at the differences between the original painting and its photographic recreation, we are encouraged to reflect more deeply on the meaning and associations of certain features in both.

In the case of costume designer Shasta Schatz, producing a photographic recreation means staying as faithful to the original painting as possible. Schatz reproduces the intricate details of ‘Portrait of a Woman Holding a Clock’ with remarkable accuracy. The portrait (also known as ‘Portrait of an African Slave Woman’) is the only surviving fragment of a larger painting created around the 1580s, and attributed to Italian artist Annibale Carracci. Schatz was inspired by the exhibition ‘Revealing the African Presence in Renaissance Europe’ in 2013. By recreating this anonymous 16th-century sitter, who would orginally have been at the edges of the painting, Schatz was able to “bring our subject to the forefront and give her the focus that she deserves” (as she explains on her blog which tracks the process of the project from start to finish).

The photographic recreation draws attention to certain important details in the sitter’s appearance, which help us to get a better sense of who she was. The three pins in her bodice, for example, could indicate that this woman was a seamstress, as suggested by fashion historian Kenna Libes. Her black dress implies her elite status, since black dyes were expensive and sought-after at this time: Schatz’s photographic recreation conveys the rich, shiny texture of the black fabric. Of course, as Nicholas Hall (scholar of Black fashion and visual culture) points out, her clock is also significant. It is an engraved ormolu table clock, a luxurious objet d’art which represented the latest technology of the time (Schatz used a 3D printer to recreate the clock). All of these details reveal that there is a strong possibility that the woman in this portrait was not enslaved, but rather a free working woman in 16th-century Italy.

American artist Mickalene Thomas adopts a different approach in some ways, in the sense that she gives Black women a presence in famous paintings, in the place of sitters who are white in the originals. Her 2013 mixed media collage ‘Sleep: Deux Femmes Noire’ (woodblock, screenprint and digital print) enters a dialogue with Gustave Courbet’s 1866 painting ‘Le Sommeil’ (Sleep), which famously depicts two women lying asleep in an erotic embrace. In another work, ‘Le déjeuner sur l’herbe: trois femmes noires’ (2010), Thomas replaces Manet’s two dressed men and naked women with three Black women who all look directly at the viewer. On the process of taking the photograph, Thomas explains: “When I was looking through the lens and trying to compose the image I wanted to have the depth of field that Manet has with the woman in the background, and it created that same environment with the Matisse sculpture taking the place of the fourth figure. Everything fell into place. Everything felt right. I didn’t have to try reconstructing things or forcing things. I saw it and I responded and it worked.”

If you like what we’re doing at Athena Art Foundation, please consider supporting us with a donation

(Written by Esme Garlake on behalf of Athena Art Foundation, October 2022)