LGBT+ Art Histories: February Pick of the Month

It is LGBT+ History Month in the UK, and we wanted to celebrate by asking six art historians from the LGBT+ community to choose one of their favourite pre-20th-century artistic representations of queer love and experience. Here is what they chose…

Detail of Elizabeth Etchingham (Image: Wikipedia)

Etchingham Parish, Sussex (Image: explorechurches)

Detail of Agnes Oxenbridge (Image: Wikipedia)

Unknown artist, The Brass of Agnes Oxenbridge and Elizabeth Etchingham, c. 1480, brass, Etchingham Parish, Sussex (Image: Wikipedia)

Baylee Woodley: The Brass of Agnes Oxenbridge and Elizabeth Etchingham, 1480

This is The Brass of Agnes Oxenbridge and Elizabeth Etchingham dating to around 1480. If you ever find yourself in Sussex, you can visit this brass yourself at the Etchingham Parish. I recently went myself to see this brass - making what I called a sort of sapphic pilgrimage - and that is one of the reasons I chose this as my artwork to share with you during this LGBTQ+ History Month.

This memorial brass commemorates an evidently intimate relationship between two women, Elizabeth Etchingham and Agnes Oxenbridge, who were buried together in Etchingham Parish. The inscription along the bottom requests God’s mercy for them both. Elizabeth is shown on the left with her hair down and she is quite a bit smaller than Agnes. This likely symbolizes her being both unwed and young when she died in 1452 in her mid-twenties. Agnes is shown on the right and (although she too seems to have remained unwed) she is shown as a more mature woman. This is likely because she was in her fifties when she died in 1480. Judith Bennett writes about this brass being designed in the style of memorial brasses for married couples, but with additional intimacy. Unlike other brasses from this time, which often show couples looking straight ahead, Agnes and Elizabeth face each other, looking into each other’s eyes. It was unusual for Agnes to be buried with Elizabeth instead of in the Oxenbridge mausoleum, so both of their families must have agreed for it to have happened. The initial request for the site of burial most likely came from the (now lost) will of Agnes herself.

I remember how meaningful it was to read Judith Bennett’s chapter on this brass in The Lesbian Premodern (2011) when I just beginning to ask whether or not queer art histories were out there. This answer is, of course, yes! They are everywhere! But this was not always as common sense to me as it is today, so this brass reminds me why I want to keep sharing queer art histories with others.

Baylee Woodley is a PhD student at the University College London and the current curator of Queer Art History. This educational resource and archive of queer art and culture was created by transgender activist, artist, and Point Foundation scholar Casey Hoke in 2017.

Queen Njinga Mbandi (Anna de Sousa Nzinga), by Achille Devéria, printed by François Le Villain, after Unknown artist, hand-coloured lithograph, 1830s, 48.8 x 35.8 cm, National Portrait Gallery, London (Image: NPG)

Bi History: Ngola Nzinga Mbandi, hand-coloured lithograph, 1830s

Ngola Nzinga Mbandi, leader of Ndongo and Matamba, was born in the early 1580s to the ruling family of the Kingdom of Ndongo (what is now Angola). She became leader after her brother’s death in 1626, which some sources suggest she was responsible for. Despite being deposed by Portuguese colonists, Njinga Mbandi fought for the independence of her kingdom over the course of her 37 year reign. She used her political skills and military strategy to gain alliances and to resist the expansion of the slave trade (she offered refuge to people who escaped enslavement). Njinga Mbandi ultimately transformed her Kingdom into a commercial state to rival Portuguese colonies.

This hand-coloured lithograph, housed in the National Portrait Gallery in London, was printed in the 1830s by François Le Villain, based on the design by an unknown artist. It presents Nzinga Mbandi in a lavish crown and brightly coloured cloak that exposes her bare breast. Although there is an elegance and nobility in this depiction, it is a starkly Eurocentric representation. Her bared breast reflects the problematic trait in many 19th-century European depictions that overtly sexualises Black female sitters. This sexualisation is simultaneously being used to create an impression of ‘otherness’ (in opposition to supposed European modesty) to justify colonial power dynamics. Notably, Nzinga Mbandi’s non-gender conformity is completely overlooked: her breast, rosy cheeks, red lips and earrings all cast her in relation to 19th-century European ideals of feminine beauty (her name is also presented in its European state, Ann Zingha).

Njinga Mbandi used the honorific Ngola, which can be translated to mean king, and dressed in traditionally male clothing. Her relationships with people of all genders have been subject to much speculation, including having a large number of ‘chibados’ in her court - a group of gender non-conforming people who dressed outside defined gender roles and had relationships which were viewed as homosexual by colonial eyes. In their book ‘Boy-Wives and Female Husbands: Studies in African Homosexualities’, Stephen O. Murray and Will Roscoe remind us that Njinga Mbandi’s court organisation “was not some personal idiosyncrasy but was based on beliefs that recognized gender as situational and symbolic as much as a personal, innate characteristic of the individual”.

Bi History is an Instagram account that explores the history of bisexuality and highlights the role of bisexual+ activists in LGBTQ+ history.

Modern statue of Njinga Mbandi in Luanda, Angola (Image: planetoverprofit.org)

European medieval manuscript (as seen on bihistory’s account)

Thomas Gainsborough, The Blue Boy, 1770, oil on canvas, 177.8 x 112.1 cm, Huntington Art Museum, California (Image: Wikipedia)

Dan Vo: The Blue Boy by Thomas Gainsborough (1770)

To mark LGBT+ History Month I have chosen The Blue Boy (1770) by Thomas Gainsborough. It was partly to mark the happy occasion of his return to the collection after spending one hundred years in The Huntington (the painting was sold at auction in 1922). In the 18th century when Blue Boy was painted, it exemplified a culture of 'sensibility' in Britain that demonstrated enlightened values and refinement. However, some feared it was a step away from masculinity. David Garrick, a friend of Gainsborough's, suggested it had elements in common with the dandy or molly of Georgian London. Many would follow who would draw attention to the queer properties of Blue Boy, with a long lineage of queer folk who have reworked the image in their vision over the years.

For example, the painting was subverted in the 1974 premiere issue of Blueboy, a gay men’s magazine, named after the painting. Here, a handsome athlete stands in. Although he has removed his breeches, the feathered hat has shifted to hide his modesty. The pastoral setting is made seductive. The cover even features a risqué graphic design of a double ‘b’ hinting at a rather ambitious phallus. The bemused model holds our gaze knowingly. An advert inside proclaimed a brotherhood of ‘The Blue Boy’ that is, “suave, cultured, sophisticated, discrete, sincere... a philosophy that Gainsborough’s 'Blue Boy' expresses so very clearly to the discerning.” Discrete seems antithetical given the large 24-carat gold medallion with a Cloisonné figure of Blue Boy affixed, offered for sale so men could broadcast their proclivities via their camp accessories.

To see the cover which the archivist of Blueboy magazine, Miss Kitty, kindly recovered for us along with another contemporary spin on Blue Boy by queer visual artist Kehinde Wiley (who currently has an exhibition at the gallery), you can read my full article written recently for the National Gallery here.

Dan Vo (@DanNouveau) is a Patron of LGBT+ History Month as well as Project Manager of the Queer Heritage and Collections Network. The network which assists galleries, libraries, archives and museums in their research on queer art history. Additionally, he is Marketing Manager at Queer Britain, the first LGBTQ+ museum in the UK due to open in Spring 2022.

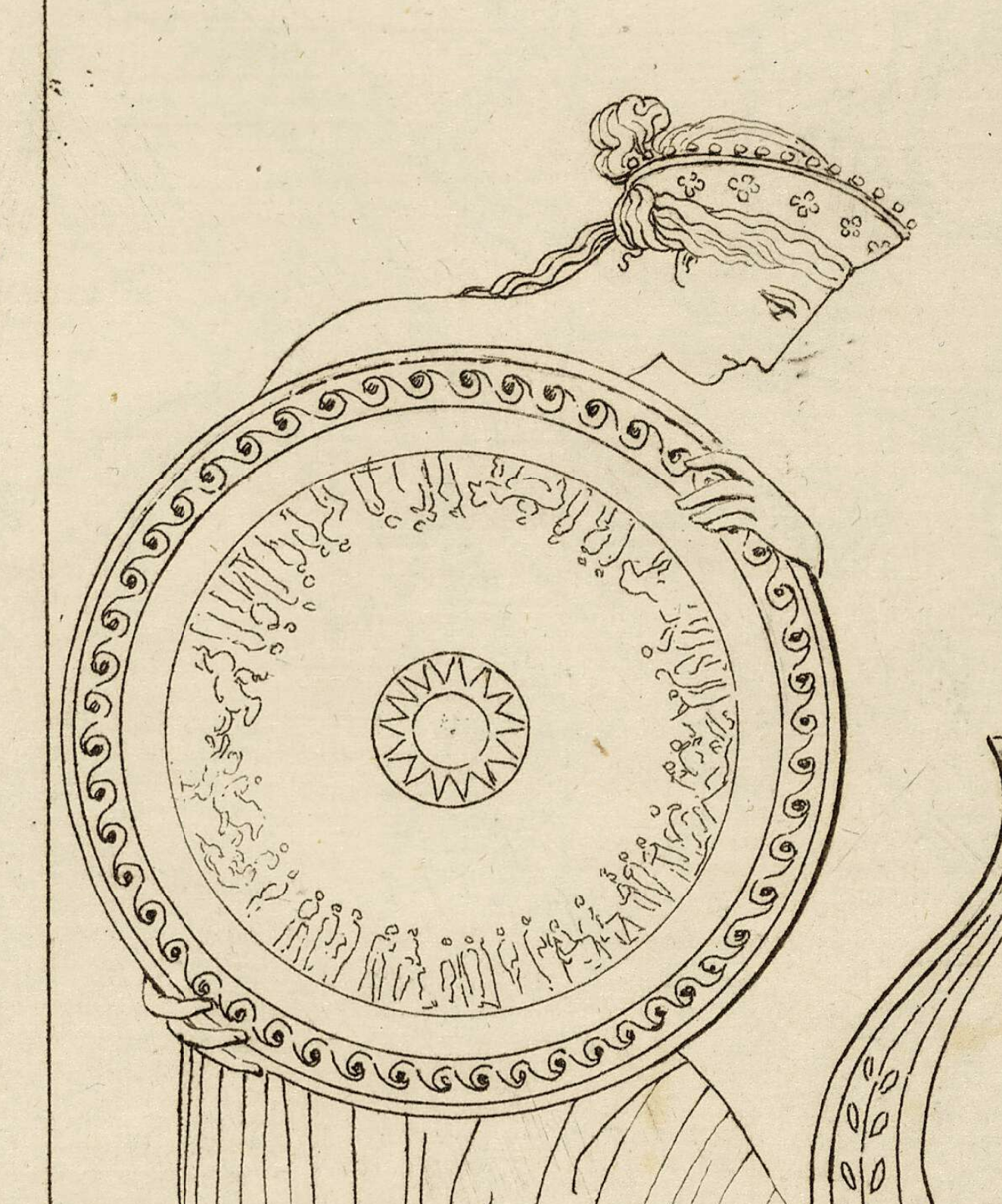

Loïc Desplanques: Achilles Mourning Patroclus by John Flaxman, 1793

John Flaxman, Achilles Mourning Patroclus, 1793, engraving, 18.9 x 28.4 cm, British Museum, London (Image: British Museum)

First published in 1793, this engraving is one of 34 illustrations of the Iliad drawn by British sculptor and draughtsman John Flaxman. This scene depicts ancient Greek hero Achilles, consumed by grief, lying draped over the lifeless body of his beloved Patroclus. Two anonymous figures hide their faces in mourning to the right of the bed, and to the left Achilles’ mother, the immortal nymph Thetis, arrives bearing newly-forged armour for her warrior son.

Despite the engraving’s apparent simplicity, along these few, sparse lines can be traced a history of the love between men, and of the tragedy that is so often associated with it. Although this particular scene has been depicted by several artists, notably in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, Flaxman introduces a slightly surprising tone. It is an intimate and tender portrait of two lovers, embracing softly in bed, as gently as if they were both living, and simply at rest.

The exact nature of the relationship between Patroclus and Achilles has been debated for centuries, but several sources dating back to ancient Greece assume without question that they were sexual and romantic partners. Just prior to this moment in the narrative of the poem, Patroclus has led a charge into battle wearing Achilles’ armour. Although performing brave feats in this attack, he is eventually killed, and Achilles is sunk into grief. The weight of this grief fills Flaxman’s image, and the bodies shown are bent and bowed under it. Achilles’ tensed right leg and flexed foot almost give the impression that he is being pressed down from above by the immensity of his feeling.

John Flaxman, detail of Ancient Drama Scene, c.1809, plaster, 50.5 x 374.5 x 9.5 cm, Royal Academy of Arts, London (Image: RA)

The engraving is startlingly airy and light. With no setting beyond a bed, and no background to speak of, almost half of the image is totally blank. This overwhelming whiteness, with taught black threads of line, is typical of Flaxman’s style; the two-dimensional, graphic quality gives clarity and simplicity to his illustrations. The artist was also a sculptor, and drawings like this might even be compared to blueprints for friezes or carved reliefs, where there is not much scope for depth or perspective. In fact, Flaxman was a noted sculptor of funerary monuments, and Achilles Mourning Patroclus could very easily be imagined adorning an ornate tomb.

In this particular image, the key elements of Flaxman’s style become especially significant. Since the majority of the artwork is white absence, Achilles’ loss echoes in its very composition; outside of setting, space, and time, the isolation and inertia of his grief structures the captivating, unbearable stillness of the scene. There is, however, some movement in the work — if only in a single knee. The drapery over Thetis’ leg shows the loosest, freest lines in the entire etching, indicating her stepping upwards. She arrives in this insular moment to encourage her son to return to war and fulfil his social duty as a warrior. She not only carries a helmet and a shield, but the weight of the outside world, to her son.

Achilles’ lack of action, wallowing too long in grief over his lover, is seen as unvirtuous, even unmanly — an unnatural deviation. Even though, in some circumstances, sexual and romantic relationships between men were permitted in ancient Greece, in general they were meant to be abandoned in time for the male duty of marrying and fathering children. It is not just the weight of his sorrow that bears down on Achilles, but also the expectations of his mother, the gods, fate, and his role as a hero and a man. All of them urge him to turn away from his devotion to Patroclus, and abandon his pain. Much like the more modern trope, where queer relationships are permissible in fiction or film only as long as the stories end tragically, this love had a mandatory expiration date.

John Flaxman, detail of Achilles Mourning Patroclus, 1793, engraving, 18.9 x 28.4 cm, British Museum, London (Image: British Museum)

Benjamin West, detail of Thetis Bringing the Armor to Achilles, 1804, oil on canvas, 68.6 x 50.8 cm, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, United States (Image: Google Arts & Culture)

Perhaps what is most remarkable about this little etching, however, is the attitude of Achilles’ mother Thetis as she enters. In other depictions of this episode from eighteenth- and nineteenth-century artists, she is bold, impatient almost, or simply divinely detached — keen to remind Achilles of his duty, to shake off his sentimental weakness and rush him back to war. Yet here, she pauses, bowing her head in respect, averting her gaze. Her reverence to the love and loss before her, and the sympathy in her posture, reverberates in Flaxman’s own empathetic artistic style. Like Thetis, the artist and the viewer alike are intruding upon a private, painful scene, the last minutes of a doomed love between two men. Thetis performs the role of the external viewer, with Flaxman guiding our response to the image before us through her reaction. And the nymph, though spurred on by the imperatives of normative masculinity and of fate, pauses a while — allowing her son to mourn, and to love, for just a moment longer.

Loïc Desplanques is a writer and art historian based in London, with a particular interest in the male body in nineteenth-century European art. He runs the Instagram account @_beau.ideal_ which explores the male body in the history of art.

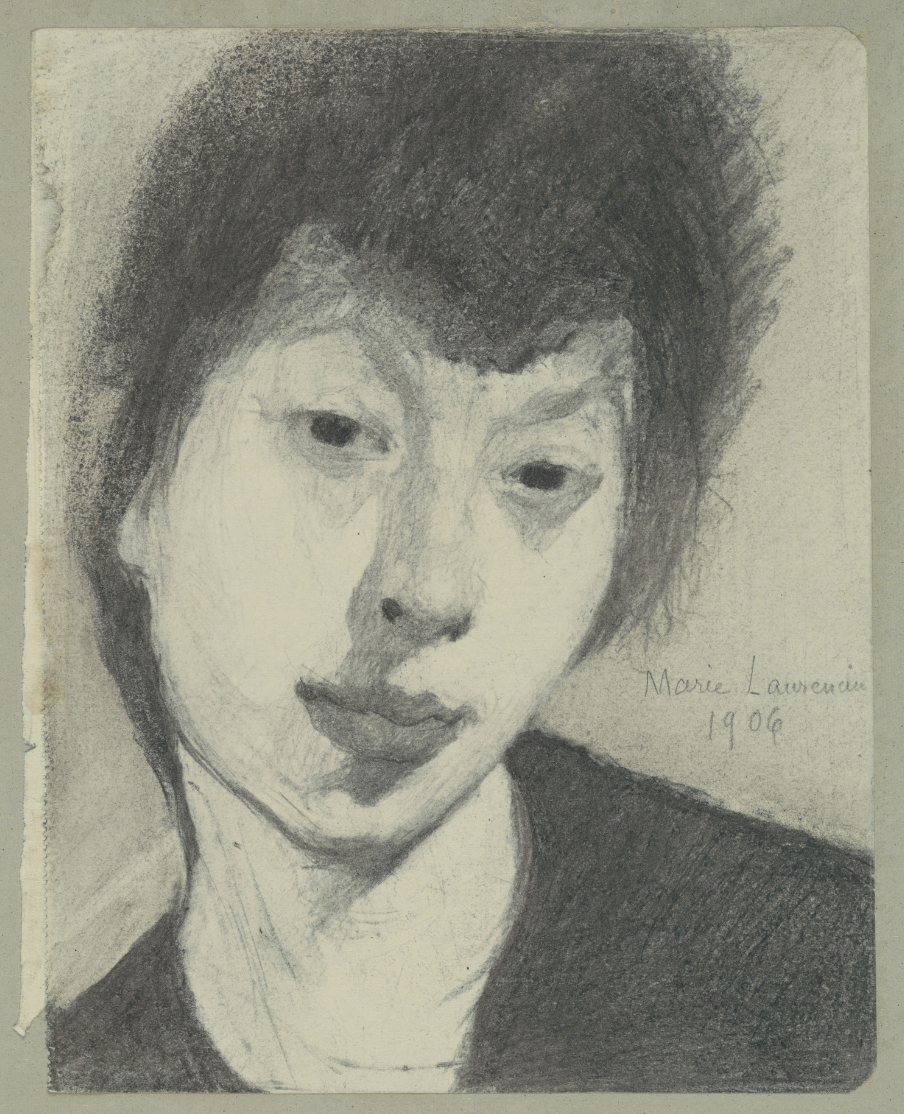

Marie Laurencin, Self-Portrait, 1906, pencil on paper, 34.9 x 31.1 cm, MoMA, New York (Image: MoMA)

Esme Garlake: Self-Portrait by Marie Laurencin, 1906

Queer histories are so often absent from art historical narratives, and yet even when artistic representations of queer experiences are found, they most often revolve around the romantic and/or erotic relationship between a same-sex couple. In everyday life, we tend to look for ‘proof’ of sexuality in this way; but particularly for those in the LGBT+ who exist in less binary spaces, this obsession with visibility can sometimes feel difficult to navigate. Similarly, pre-20th-century artworks that depict the experiences of queer people of colour are even less visible; but again, this does not signify a historical absence, but rather an absence of historical records. So I wanted to choose an artwork that represents - and celebrates - the queer self.

Marie Laurencin, detail of Le Bal élégant, La Danse à la campagne, 1913, oil on canvas, 115 x 146 cm, Moderna Museet, Stockholm (Image: Wikipedia)

The French painter and printmaker Marie Laurencin is primarily associated with the Parisian avant-garde in the early decades of the 20th-century; as one of the few female Cubist painters, her work explores images of femininity and depictions of women in her characteristic grey-pink tones. Laurencin had romantic relationships with both men and women, including the French poet Guillaume Apollinaire and the American writer Natalie Clifford Barney. Although many of Laurencin’s paintings depict pairs or groups of women, I have chosen to look at a simple pencil self-portrait drawn by the artist in 1906. The loose, sketchy style shows a self-confidence that is reflected in her direct gaze (since it is a self-portrait, this confidence is directed first towards herself, and then towards the viewer). The way that Laurencin depicts herself with her head tilted slightly to one side gives an informal tone, as if she is inviting us into her world.

This self-portrait offers an intimacy and confidence of self that I find deeply comforting. It gives me a reminder that sexuality is something deeply personal and intimate; that I can be loud and proud about it, but also hold it close to myself at the same time. This is a self-portrait that records a moment when Laurencin as an artist is exploring how she sees herself; experimenting with the textures and effects that can be achieved simply by sketching in front of a mirror. The knowledge that she was queer (to use today’s term) reminds me that whatever I am doing, however I present myself or whomever is in my life, my queerness remains just as valid and real.

Esme Garlake (@eco_art_historian) is an art historian and writer based in London. She specialises in ecological approaches to pre-20th-century art, particularly in early modern Italy.

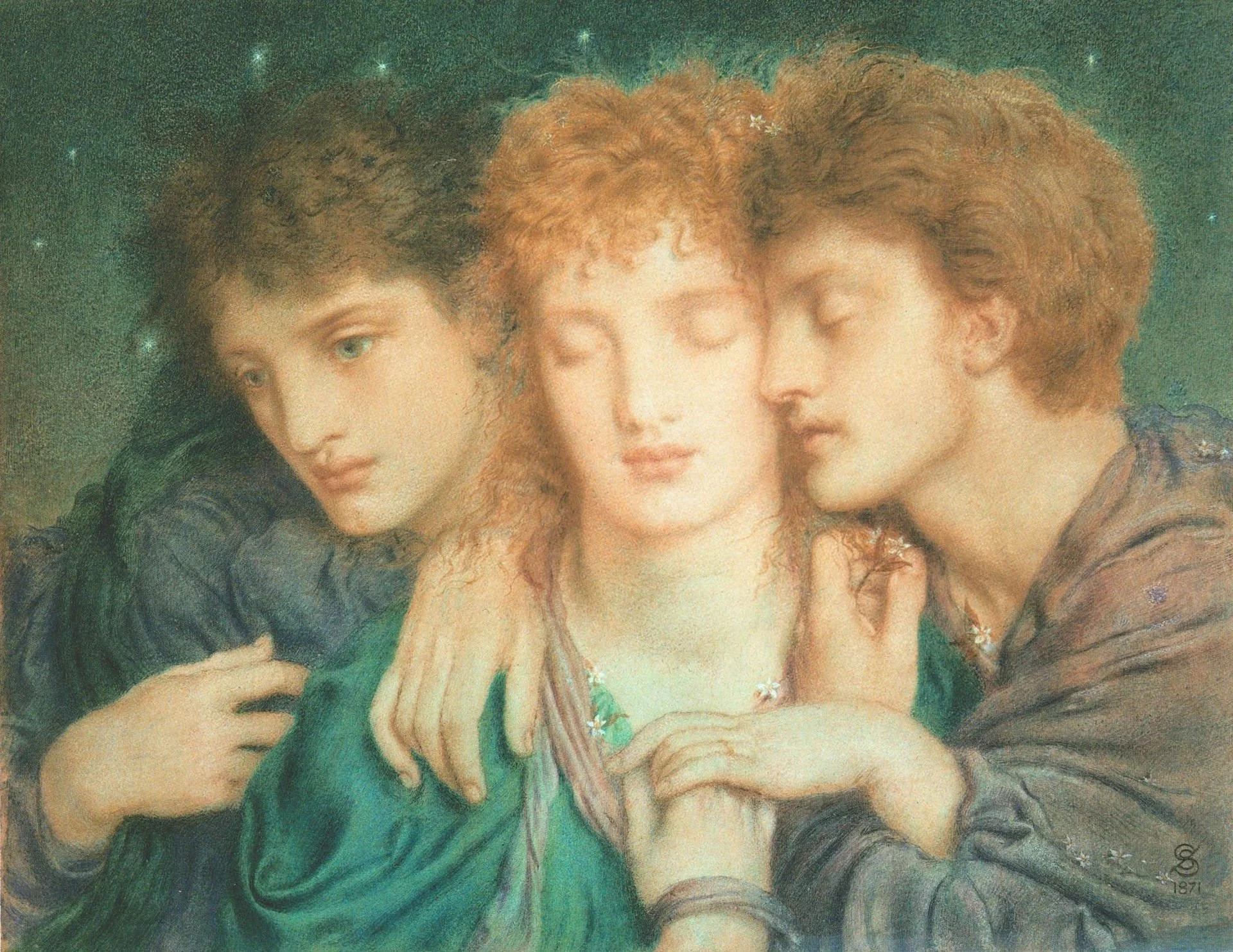

Alice Dodds: The Sleepers and the One that Watcheth by Simeon Solomon, 1870

In 1873 and 1874, Simeon Solomon was arrested for his relationships with men and, as a result, fell from his position of the ‘darling of the Pre Raphaelites’ into poverty, loneliness and alcoholism. Painted three years earlier, Solomon’s The Sleepers and the One that Watcheth holds an atmosphere of desire, longing, hope and uncertainty that, in my view, movingly raises the question of how to navigate the tensions and complexities around queer desire.

The three androgynous figures are intertwined - but two more intimately, leaving the third figure as the Other that ‘watcheth’. Yet, turned away from the couple, the third figure does not watch at all. Their vacant gaze and melancholy expression harbours an unsettled longing which turns this ‘watching’ inwardly upon themselves as Other. The exact dynamic between the trio is, however, hard to determine. Does the more ‘feminine’ figure in the middle of the scene divide the longing ‘one that watcheth’ from the affections of the more ‘masculine’ figure to the right? Or are the more ‘feminine’ figure’s wider affections prevented by the arm wrapped protectively around her? The ambiguity of their relationship leaves the image open to, perhaps, a universal queer reading that resists delineations between different queer identities.

The figures are ultimately both entangled and divided, affectionate and awaiting affection. They are bisexuality, polyamory, unrequited lesbianism and legally-forbidden homosexuality all rolled into one complex relationship. It is an image that is compellingly intriguing and I find still relevant today in its embrace of the complex and often undefinable experiences we face today as queer people.

Alice Dodds @theyoungarthistorian is a student at The Courtauld Institute interested in craft, gender and sexuality in the long nineteenth century -- which you can find her talking about constantly on TikTok.

(Curated and edited by Esme Garlake on behalf of Athena Art Foundation, February 2022)