Review: Dürer’s Journeys

by George Fountain

The National Gallery’s new exhibition, Dürer’s Journeys: Travels of a Renaissance Artist, visually presents a vital episode of art history. Born in Nuremberg, Germany, in 1471 Albrecht Dürer remains a true benchmark of pre-modern art. A skilled draughtsman, painter, and printmaker, he rose to prominence in his time, but his contribution to art history goes far beyond his own creations. During several key trips across Europe, Dürer honed his craft with each new destination and those he met along the way. He was unique in the detailed documentation of his travels; the National Gallery’s current exhibition captures this career of curiosity and ingenuity.

This sprawling exhibition lays out the evolution of an artist who recognised and, crucially, vocalised the marvel of the age in which he lived; each piece of art on display develops a sense of the wanderings (and wonderings) of a sharp artistic mind. The immediately striking feature of Dürer’s Journeys is the sheer volume of content on display in this exhibition. The collection delivers such a broad and often comprehensive overview of the artist’s body of work that visitors will certainly leave with a better understanding of the old master. It is an immensely ambitious project that succeeds in creating a sense of place through the careful division of rooms according to regions and themes. At its heart, Dürer’s Journeys is an enriching story of travel, experimentation, and the open-minded exchange of ideas; illustrating how the cross-pollination of cultural environments is fundamental to the development of art.

Albrecht Dürer, A Lion, 1494, gouache on parchment, 12.6×17.2 cm, Hamburger Kunsthalle, Hamburg (Image: Guardian)

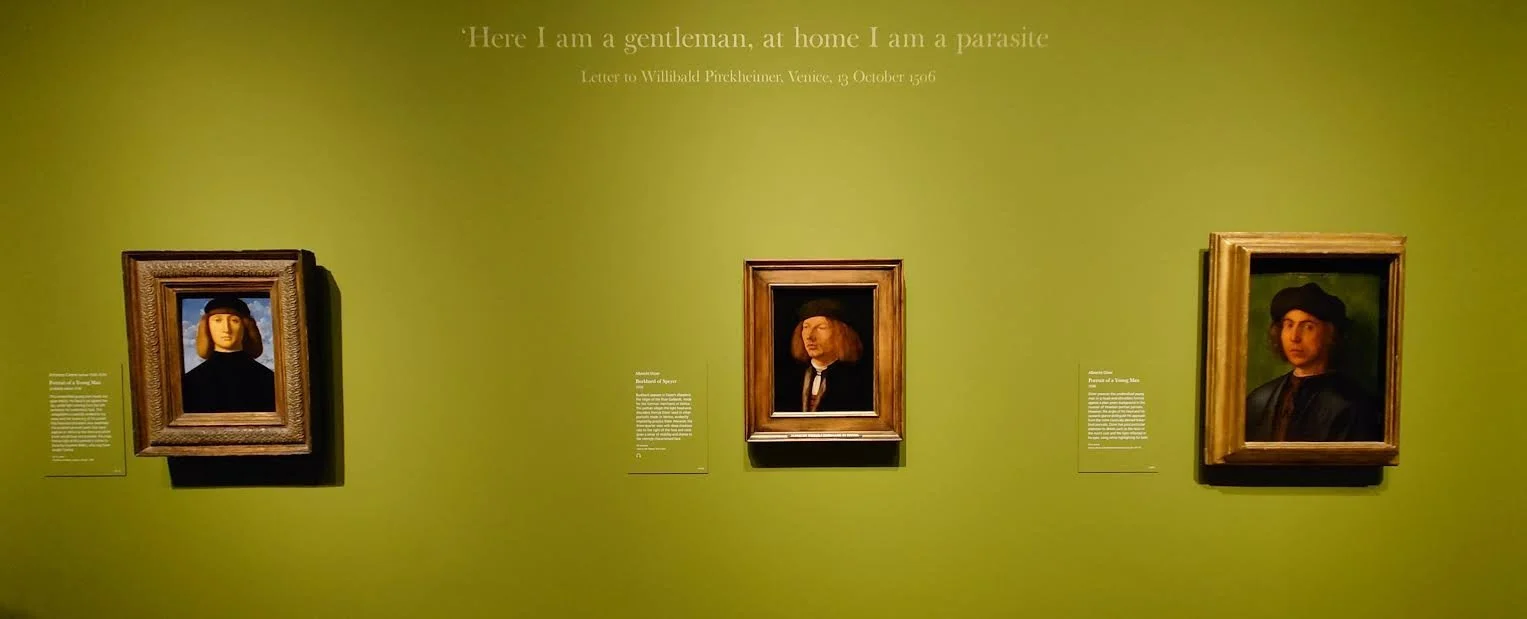

To achieve this, every room contains works by other artists of Dürer’s time, generally linked to the geographic or artistic themes that define each compartmentalised space (conveniently distinguished by colour of room). For some visitors, this approach is a source of frustration: some reviews have argued that there is not actually enough art by Dürer himself, and that the presence of contemporaries detracts from the brilliance of his own work. This is a flawed criticism on two counts. Firstly, the presence of Dürer’s fellow artists is vital to the topic of the exhibition: it is a demonstration of artistic discovery, not just an intellectual trip around Europe. In order to demonstrate how Dürer was inspired by his contemporaries (as well as those he influenced), it is essential that the exhibition offers visual evidence of the worlds he visited. In the context of the Northern and Italian Renaissances, no piece of art, technique nor idea is created in vacuum. Comparing Dürer with the great contemporary painters of Italy or Flanders is imperative to presenting him within the artistic spheres with which he interacted.

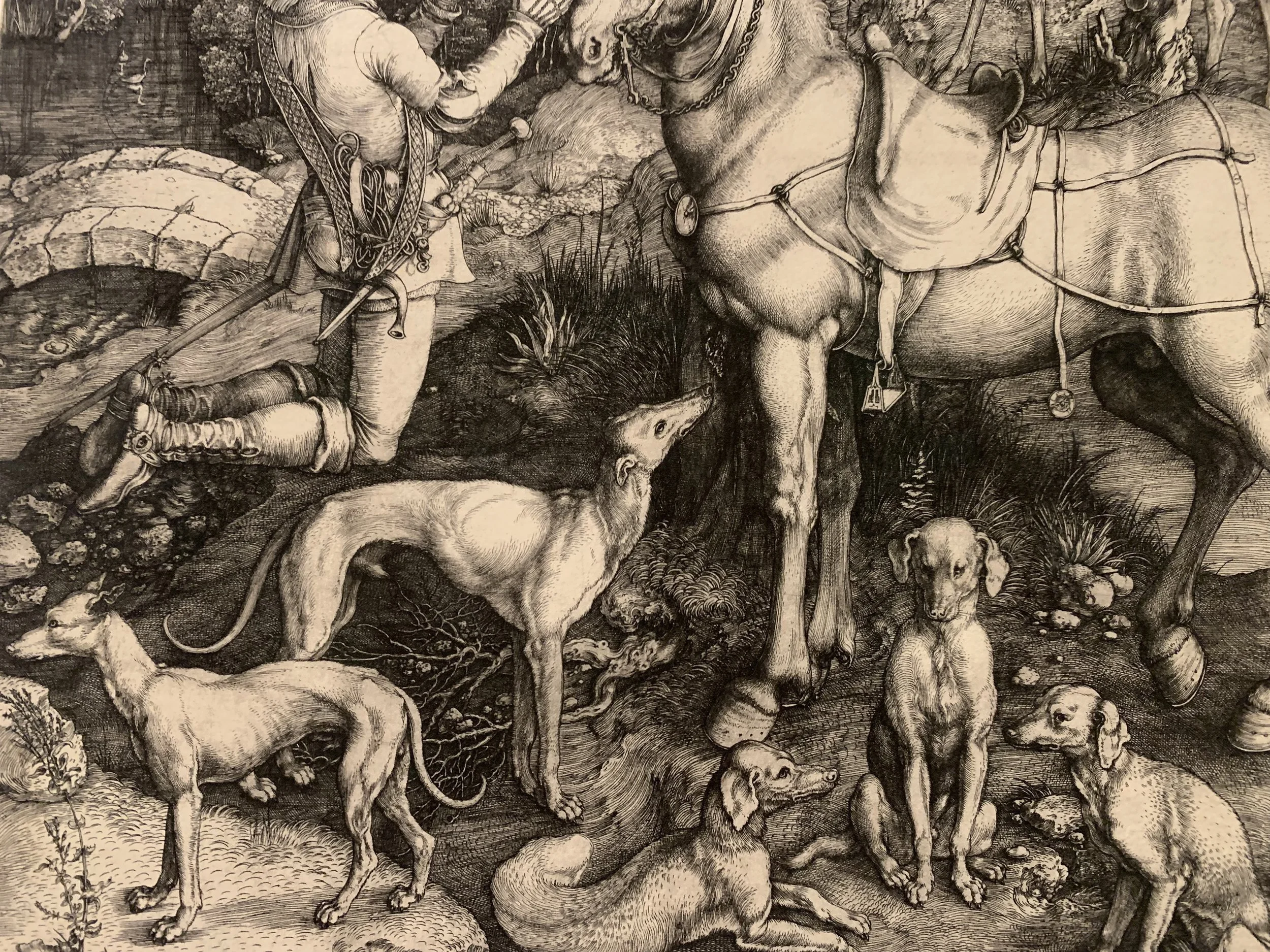

Secondly, no one can reasonably argue that this exhibition short-changes the audience on Dürer. Although some of his most well-known artworks – such as the iconic Self-Portrait as Christ (1500) – are noticeably absent, the collection still comprises of an immense array of works by the German master. Accompanying his meticulously detailed engravings and prints (the true highlights of the collection), works of watercolours, oils, chalks, pen and ink and wash contribute to a burgeoning mix of media, all unified by one hand and the increasingly familiar ‘AD’ signature. Yet as wonderfully rich as the format and content of the exhibition is, it sometimes feels like the thematic approach loses its way at points; perhaps in part due to the sheer number of works on display. There are times when the presence of certain works feels tenuous or unclear in their link to the theme of a room.

One example of a missed opportunity to explore Dürer’s artistic exchange is found in relation to the Venetian painter, Giovanni Bellini. Early in the exhibition, the influence of the two artists on each other – during Dürer’s trip to Venice – is introduced, and Bellini’s numerous Madonnas are presented as a ‘particularly evident’ influence on Dürer’s Madonna and Child. However, despite the fact that multiple examples of Bellini’s own portrayals of the Virgin Mary and the Christ Child are housed in the National Gallery’s permanent collection, it is a shame that not one is included here for the audience to draw any of their own visual comparisons. It is odd to simply presume the visitor’s prior knowledge of Bellini’s artistic styling and approach to the subject-matter. Instead, when a painting by Bellini does feature in this exhibition, it is to demonstrate what feels like a comparatively trivial point; the shared use of an ox’s behind as a device for perspective in both Dürer’s engraving of the Prodigal Son (c. 1496) and Bellini’s The Assassination of Saint Peter the Martyr (c. 1505-7).

Giovanni Bellini, The Virgin and Child, c. 1480-90, oil on poplar, 90.8 cm x 64.8 cm, National Gallery, London (Image: National Gallery)

Albrecht Dürer, Madonna and Child (obverse), c. 1496-99, oil on panel, 52.4 x 42.2 cm, National Gallery of Art, Washington (Image: NGA)

Other featured works could potentially spark pertinent discussions of modern issues. The antisemitism in Dürer’s Christ and the Doctors (1506), the representation of indigenous peoples, and the intriguing career of female illuminator Susanna Horenbout (1503-1554) all invite further investigation. However, these avenues are not explored in as much depth as one might hope, since the exhibition is already swelling with such a variety of ideas and images. Nonetheless, when the tone and purpose of a room comes across clearly, visitors have a captivating sense of the artist’s life and work. Some spaces – such as the final room’s exploration of Dürer’s religious progressions during the reformation – offer contained and digestible microcosms of the artist which could arguably be their own exhibitions.

Throughout the exhibition, there is the reassuring presence of Dürer’s own voice. Given that he was a man who actually recognised the cultural movements flourishing around him and ‘built up an encyclopaedia of his own time’, the artist offers a unique perspective on the spheres through which he travelled. Words from his letters and journals are woven through the exhibition. This not only provides context to the artworks on display but also safeguards against a stuffy, anachronistic, or purely historical view of his career and oeuvre. Ultimately, the National Gallery’s exhibition sets out to plunge its visitors into the richness of worlds that Dürer travelled through; to better understand what he took with him and what he left behind. It is a whistle-stop tour of a career defined by discovery, and an invaluable touchstone to any visitor’s understanding of the European Renaissances and pre-modern art.

George Fountain is an art historian and writer based in London. With a background in Ancient Greek sculpture, he holds an MA from the Courtauld Institute of Art where he specialised in sixteenth-century Venetian art.

Albrecht Dürer, Detail of Portrait of a Young Man, 1521, charcoal drawing on paper, 37.8 x 21.1 cm, British Museum

Albrecht Dürer, Christ Among the Doctors, 1506, oil on panel, 65 cm × 80 cm, Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid (Image: Wikipedia)

A coloured wall in the exhibition (Image: George Fountain)