The Female Nipple in Art History

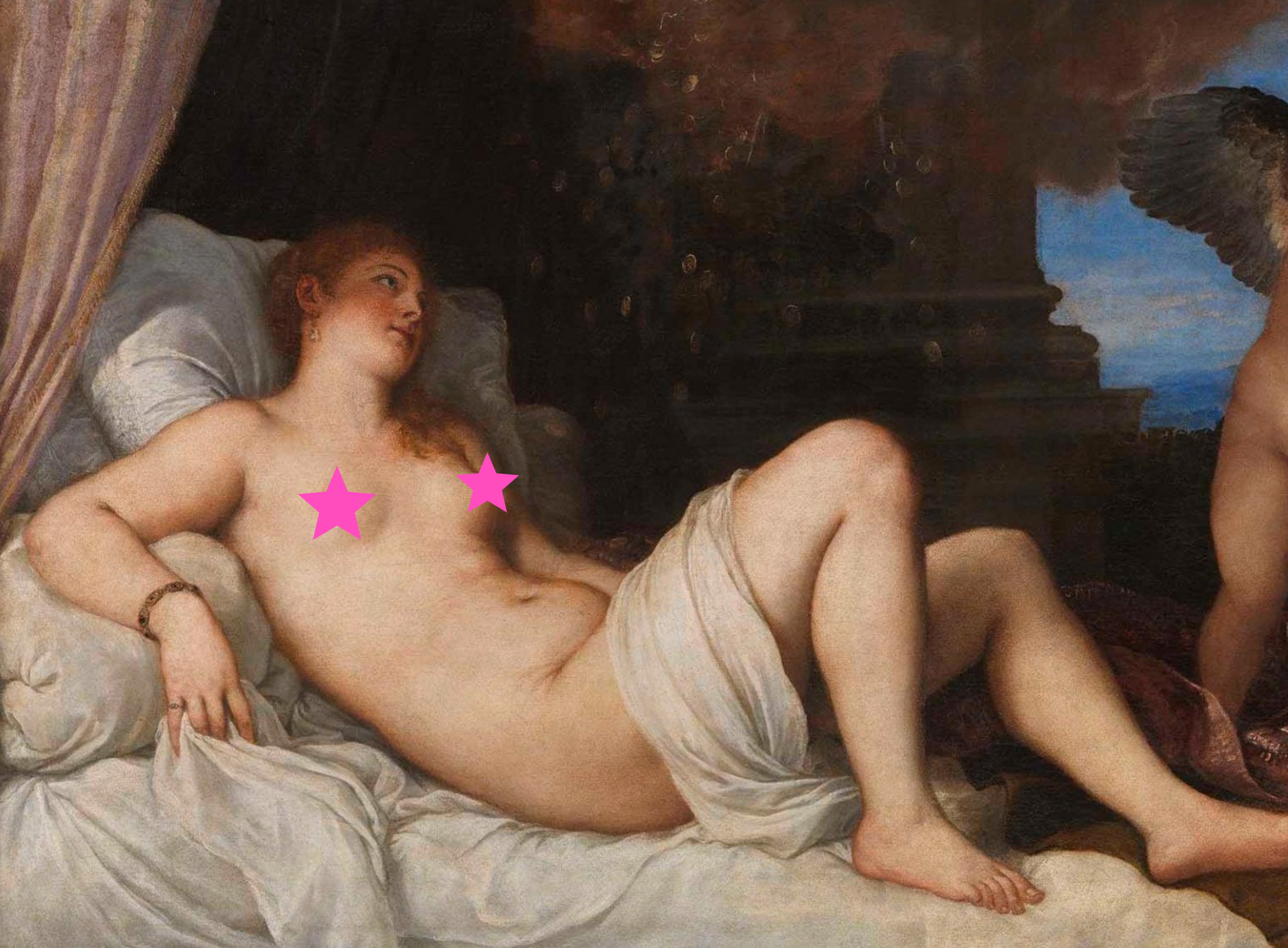

Titian, Danaë (censored), 1544-46, oil on canvas, 120 x 172 cm, National Museum of Capodimonte, Naples (Image: Wikipedia)

In any art gallery of European paintings, women’s nipples are everywhere. These galleries are full of nudes and, as famously declared by 1980s feminist art group Guerrilla Girls, ‘less than 5% of the artists in the Modern Art Sections [of the Met] are women, but 85% of the nudes are female’. The statistics are just as damning in pre-modern art sections. Female nudes are consistently framed as acceptable forms of representing female bodies, and yet naked female bodies outside of art galleries continue to be seen as inappropriate, offensive or sexualised.

Kenneth Clark famously defined the difference between nude and naked: ‘to be naked is to be deprived of our clothes, and the word implies some of the embarrassment most of us feel in that condition. The word ‘nude’, on the other hand, carries, in educated usage, no uncomfortable overtone… it projects [an image of] a balanced, prosperous, and confident body: the body re-formed.’ The idea of nakedness as embarrassment is particularly pertinent for women: historically and currently, female physicality has been associated with feelings of shame. We might think of how in many places women still struggle to nurse their babies in public due to social taboos.

Robert Lefèvre, Portrait of Pauline Bonaparte, 1806, oil on canvas, 65 x 53 cm, Palace of Versailles (Image: Wikipedia)

Joseph Duplessis, Portrait of Princess Marie Thérèse Louise of Savoy, c. 1775-99, oil on canvas, Metz Museum (Image: Wikipedia)

However, female nipples have not always been as controversial or sexualised as they are today. In eighteenth-century France, it was far more shocking for a woman to flash her ankle or knee than her breasts. A woman’s breasts said more about her status in society than it did about sexuality. In fact, a young woman showing off her breasts implied innocence and purity (having not yet nursed a child, she was presumably still a virgin), and the exposure of one breast also typically symbolised strong moral character. Furthermore, the fashion for extremely low necklines, with corsets that pushed the breasts upwards almost to armpit level, meant that it was far more common for a woman to even unintentionally expose her nipple in public. Mathematician and natural philosopher Émilie du Châtelet famously started the fashion trend for applying rouge to enhance the appearance of women’s nipples. Even Napoleon’s sister, Pauline Bonaparte, had her portrait painted in a sheer dress (although this was still considered rather scandalous at the time).

Peter Paul Rubens, The Origin of the Milky Way, 1636-37, oil on canvas, 181 x 244 cm, Museo del Prado, Madrid (Image: Wikipedia)

In sixteenth-century European art, the eroticisation of female bodies were increasingly justified through the use of mythological subjects, since artists could claim that they were harking back to the classical nudes in ancient Roman and Greek art (in other words, claiming an ‘educated usage’ of nakedness). In Rubens’ ‘The Origin of the Milky Way’, he visually reflects the narrative significance of the female nipple by placing her breast at the centre of the canvas and, in this way, drawing the viewers’ eyes to it. Even religious subject matters included eroticised female bodies. The Italian painter Parmigianino frequently depicted the Madonna with very visible nipples, seen through the clinging fabrics of her dress. He could get away with this because he adhered to the classicising visual language of the time which justified showing the Virgin’s body in potentially eroticising ways.

Parmigianino, detail of Virgin and Child with Saint John the Baptist and Mary Magdalene, c. 1535–40, oil on paper laid down on panel, 75.9 × 59.7 x 3 cm, The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles (Image: Getty Museum)

Even today, if a woman’s nipple is depicted in a painting on the walls of a public gallery, she will be seen as beautiful, feminine and culturally valuable (rather than offensive or inappropriate, as female nipples tend to be seen in other public spaces). Over time, the intellectualisation of female bodies continues to justify their eroticisation. The only place where the female nipple in art is still treated with harsh censorship is on social media platforms. Instagram, Facebook and TikTok censors all images of female nipples, often including historical art works. This censorship is clearly problematic on a number of levels; for example, there is a disproportionate censoring of the bodies and work of those in marginalised communities. It also completely disregards nuances about cultural differences, and how what is deemed inappropriate in one culture may be entirely acceptable in another. The censorship of female nipples in historical works of art exemplifies is just one example of how readily – and problematically – we project modern connotations onto cultures of the past.

(Written by Esme Garlake on behalf of Athena Art Foundation, February 2022)