Fashioning Gainsborough’s Women

by Jane Simpkiss

Thomas Gainsborough, The Linley Sisters, 1771, oil on canvas, 199 x 153.5 cm, Dulwich Picture Gallery, London (Image: Google Arts & Culture)

After returning to London earlier this year, Thomas Gainsborough’s Blue Boy is about to wing its way back to America, ending a fascinating display at the National Gallery, that saw the portrait back on show in the UK after a one-hundred-year absence. The flamboyant costume of the sitter is so sensational that, unlike most British portraits of the period, the work is known by the colour of a suit, rather than the name of a sitter. Gainsborough’s painting perfectly encapsulates the eighteenth-century passion for masquerade and costume, particularly for the Van Dyck costume which the Blue Boy sports.

The type of costume worn in a painting can reveal fascinating information about the personality of a sitter and artist, particularly the traits they wish to promote to the viewer. In the eighteenth century, for example, Van Dyck costume offered a timeless quality to a portrait, aligning the artist’s work with those by the seventeenth-century master and implying the rich, dynastic inheritance of a sitter (whether this was merited or not). The National Gallery makes this point well by pairing Gainsborough’s Blue Boy with its likely inspiration, Van Dyck’s Lord Stuart and his Brother, Lord Bernard Stuart, 1638, but the display is all the more interesting for the comparison with female portraits.

Thomas Gainsborough, The Blue Boy, 1770, oil on canvas, 177.8 x 112.1 cm, Huntington Art Museum, California (Image: Wikipedia)

Anthony van Dyck, Lord John Stuart and his Brother, Lord Bernard Stuart, c.1638, oil on canvas, 237.5 x 146.1 cm, National Gallery, London (Image: Wikipedia)

In addition to these works are two Gainsborough portraits showing distinguished female performers of the age – Sarah Siddons, the renowned tragedian, and Mary and Elizabeth Linley, famous singers of oratorios and members of the musical Linley family, known as ‘the Nest of Nightingales’. Whilst these paintings might not be known by the colour of the clothes worn by the sitters, the costumes in these works are potentially more interesting than those of their male counterparts, revealing fascinating glimpses into the lives of the women that wore them.

Britain’s Georgian society could be particularly critical of women in the public eye, particularly professionals like actresses or singers, and their portraits could come under intense scrutiny. The wrong choice of pose or costume could spell disaster for a woman’s reputation, confirming society’s inherent belief that a woman in public was a woman of loose morals and character. Such was the case with the extroverted amateur musician Ann Ford, painted by Gainsborough in 1760. In this portrait, Ford is depicted holding a daringly male pose, idly tousling her hair with her legs crossed, an informal position that was, for many, far too bold for a young woman of the period. Mary Delany, a notable commentator of the age, stated that she would be ‘very sorry to have anyone I loved set forth in that manner’.

Thomas Gainsborough, Ann Ford (later Mrs Philip Thicknesse), 1760, oil on canvas, 197.2 x 134.9 cm, Cincinnati Art Museum, Ohio (Image: Google Arts & Culture)

Thomas Gainsborough, Mrs Siddons, 1785, oil on canvas, 126 x 99.5 cm, National Gallery, London (Image: National Gallery)

In the portraits of Mrs Siddons and the Linley Sisters, the sitters have clearly attempted to avoid such comments, manipulating their image through the choice of costume and setting. Mrs Siddons was depicted numerous times throughout the period, most often as one of her characters. Gainsborough’s portrait, however, distances her from her theatrical profession, and shows her beyond reproach, dressed in a fashionable blue striped gown, with black beaver hat, yellow mantle and fox-fur muff. This depiction was eminently suitable for a woman who was no mere actress but the grande dame of the English theatre. The image conceals Siddons’ incredibly hardworking nature (she was so busy she may have only sat for Gainsborough once); here she appears as a lady of leisure.

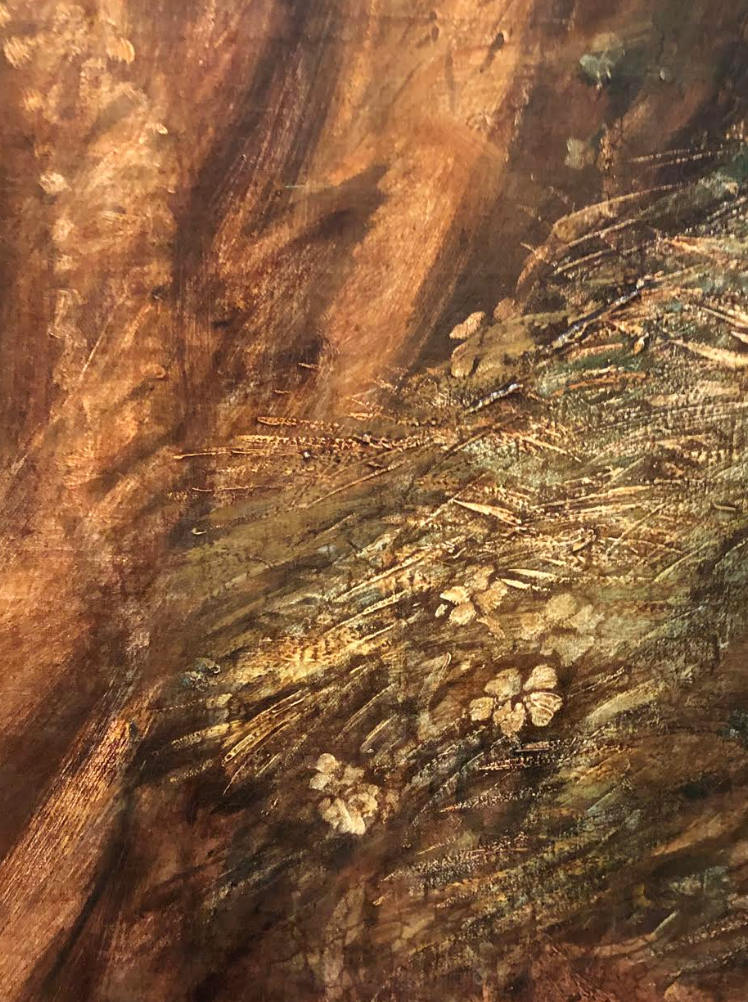

The clothes worn by the Linley sisters also reveal their attempts to control their image, walking the fine line between public promotion and appropriate, demur femininity. Whilst Elizabeth Linley’s dress shares is the same colour of silk as seen in The Blue Boy, its meaning is very different. Set against a blurred, almost murky landscape, The Blue Boy stands out flamboyantly; conversely, the Linley sisters blend into their surroundings. Although Gainsborough references the Linley sisters’ profession by including a guitar and sheet music (thought by some to be for a song written by Mary’s future husband, the amusingly-named Mr Tickell), they are not on a stage or in a concert venue but shown in the lush and verdant countryside. In this way, their profession as singers is rendered a romantic rather than professional pursuit and the women paragons of sensibility and virtue. Such is their affinity for nature, a lauded trait in a woman of this time, that Mary’s yellow dress literally merges with the yellow grass she sits on, whilst Mary’s reflects the blue sky above. Yellow and blue dresses were extremely popular in this period, and so here Gainsborough still shows his sitters as fashionable, whilst carefully avoiding any trace of the stigma their profession might otherwise entail. Mary’s direct and unwavering gaze out at the viewer is, alongside their musical trappings, the only other reference to their familiarity with the public gaze and being the centre of attention.

Thomas Gainsborough, The Linley Sisters, 1771, oil on canvas, 199 x 153.5 cm, Dulwich Picture Gallery, London (Image: Google Arts & Culture)

Thomas Gainsborough, Detail from The Linley Sisters, 1771, oil on canvas, 199 x 153.5 cm, Dulwich Picture Gallery, London (Image: Google Arts & Culture)

Painted in 1772, this portrait by Gainsborough also dates, like The Blue Boy, from the artist’s Bath period, where he befriended the Linley family, likely through their shared passion for music. The years 1771 and 1772 were particularly dramatic in the romantic life of Elizabeth Linley, and it is here where Gainsborough’s choice of costume and setting may hold particular significance. Elizabeth Linley, as we can see from her portrait, was extremely beautiful with an exalted singing voice. She had captured the public eye from the age of sixteen, and immediately legends and rumour began to spring up around her. Some of these stories were extremely favourable, such as one printed in a newspaper of 1770 which described the romantic moment when a bull finch – mistaking Elizabeth’s voice for its mate whilst she was singing ‘I know that my redeemer liveth’ from Handel’s Messiah – began to duet with her.

Other stories were far more scandalous. In 1771, Samuel Foote, the well-known actor-manager and dramatist, wrote and performed in the play The Fair Maid of Bath, a thinly veiled account of Elizabeth’s romantic affairs. The play follows the story of one ‘Miss Linnet’, who was torn between her repugnance for her fiancé Mr Flint (based on Elizabeth Linley’s real-life fiancé Walter Long) and her duty to her family. Complication arises when she captures the attention of Captain Racket. The play was a great success and was repeated each season until 1777. Whilst the play further catapulted Elizabeth into the spotlight, it was not the attention an eighteenth-century woman would have wanted. The fact that there was some truth in these stories added fuel to the fire. Elizabeth broke off her engagement to the older gentleman Walter Long in 1771, reputedly because of an affair with the real Racket, Captain Thomas Matthews. In 1772, desperate to escape the scandal, Elizabeth fled to France to enter a convent. Unfortunately, as is often the way with mad romantic dashes across the Channel, Elizabeth fell in love with her chaperone, the playwright Thomas Sheridan, and married him in secret. What was intended to disassociate her from notoriety only added to it, and prior to the second - and legal - marriage of Elizabeth and Sheridan in 1773, Matthews and Sheridan fought two duels for her hand.

On the surface, there is little in Gainsborough’s portrait to reveal the tumultuous developments unfolding in Elizabeth and Mary’s lives at the time of its painting. One could suggest that Elizabeth’s wistful gaze out to the left and into the distance might reveal her desire for peace away from the limelight or her passion for her lover, but this might be imposing our romantic imaginings too far upon the image. The absence of society is perhaps the only indication of the drama behind the scenes, with Gainsborough working hard to paint both women as virtuous, not scandalous.

It is interesting to consider whose idea such a setting was in this image: Gainsborough, Mary, Elizabeth, their father? Women situated in natural landscapes is a common theme in Gainsborough’s portraiture. He was known for his passion for landscape and his incorporation of such settings into his society portraits was in keeping with the fashion for increasingly informal portraits which emphasised the sitter’s affinity for the natural world. Gainsborough would paint Elizabeth Linley again in such a setting, now styled as Mrs Brinsley Sheridan, in 1785-1787. In this work, he merges the sitter once more with the landscape, the impressionistic style of painting adding a windswept look to the famous beauty. The trees bend with her body as she takes a seat in a romantic dark bower. Both works owe something to Van Dyck, Gainsborough’s great inspiration, the setting adding a poetic artifice found in certain works by the Flemish master. The sisters themselves are likely to have had some input, as would their father who carefully managed his musical brood. We know that Mary wrote to Gainsborough in 1785 complaining that the double portrait was not a good likeness. The next year she wrote to her sister praising the work which had been recently touched up by Gainsborough. X-rays have revealed a number of changes which the Linley sisters might have asked for including softening Mary’s face and lowering her hairstyle in keeping with the fashions of the 1780s. Furthermore, in keeping with current trends, the waistline of Elizabeth’s gown has been made higher and her sleeve simplified and shortened.

While artists like Gainsborough prided themselves on their ability to capture a likeness, portraits are far from perfect reproductions of people. They are battle grounds for public reputation where composition and costume become important tools in the artist’s (and sometimes the sitter’s) arsenal. While some favoured flamboyance, natural simplicity was often the order of the day, particularly in female portraits. In a society where women were so often denied a public voice, they relied on fashion to shape their image and the narratives that surrounded them. Though the costume of The Blue Boy might dazzle the viewer on entering the National Gallery’s display, it is worth taking a moment to consider the quieter clothing of the women around him, which is capable of hiding far more compelling and fascinating stories.

Jane Simpkiss is the Art Curator at Leamington Spa Art Gallery & Museum where she is responsible for the art collection and art exhibition programme. She specialises in seventeenth and eighteenth-century British and Dutch painting. Before working at Leamington Spa, she undertook freelance positions and interned at the Royal Collection Trust, Royal Museums, Greenwich and Dulwich Picture Gallery.

12 May 2022