Radical Landscapes: July Pick of the Month

Thomas Gainsborough, Mr and Mrs Andrews, c.1750, oil on canvas, 69.8 x 119.4 cm, National Gallery, London (Image: Wikipedia)

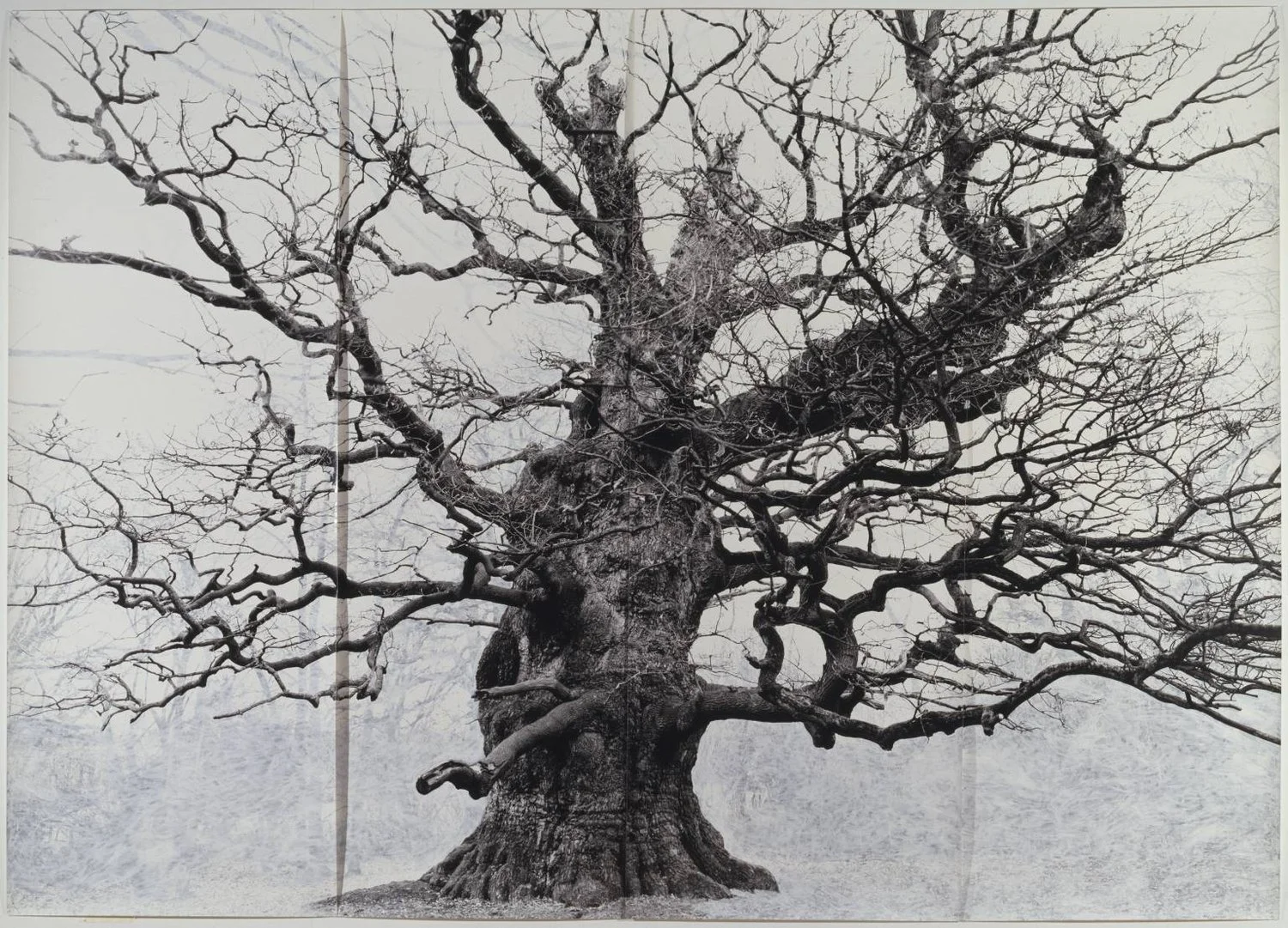

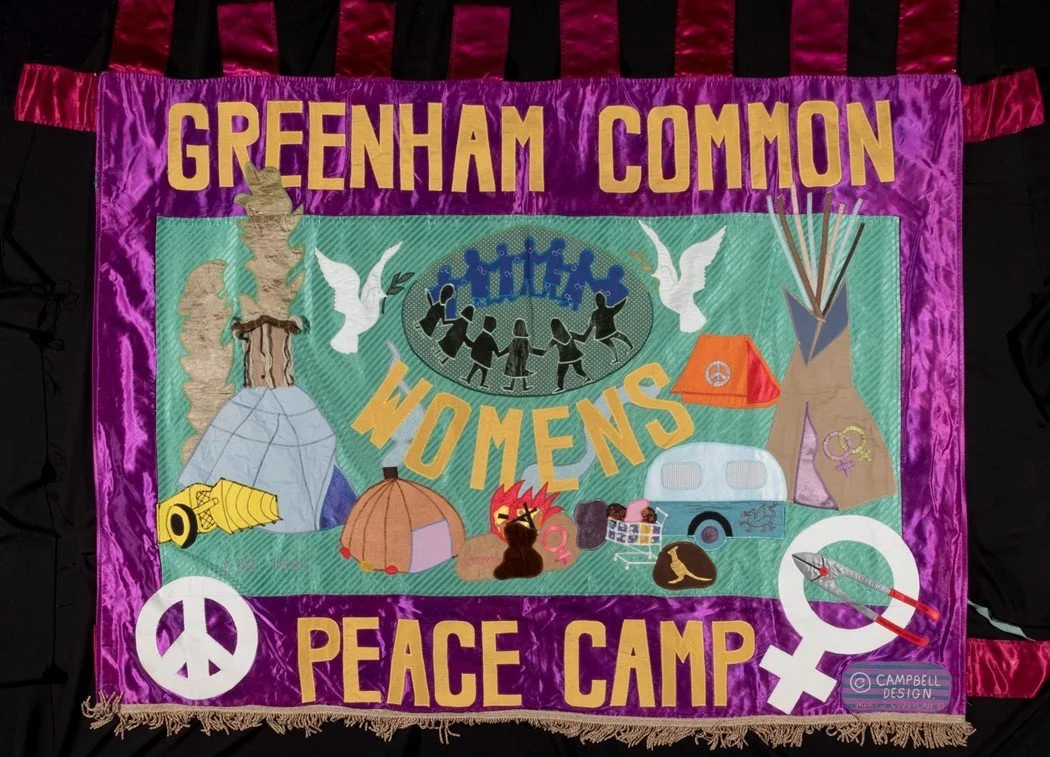

Tate Liverpool’s current exhibition Radical Landscapes explores the social and political histories of British land and landscapes, to reflect on the ‘diversity of the British Landscape and the communities that inhabit it.’ It seeks to ‘present a radical view of the British landscape in art’. The exhibition mostly includes modern and contemporary artworks and records - from still and moving images of the Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camp in the 1980s (a campaign against the requisition of the common for nuclear weapons) to Tacita Dean’s poignant Majesty (2006), a black and white photograph of a leafless and ancient oak tree. It also includes written contributions from a range of curators, artists, historians and activists, including those who are on the frontlines of the climate movement today, such as the co-founder of youth group Green New Deal Rising.

Tacita Dean, Majesty, 2006, gouache on photograph mounted on paper, 300 x 420 cm, Tate, UK (Image: Tate)

Thalia Campbell, ‘Greenham Common Peace Camp’, c.1982, The Peace Museum, Bradford (Image: Dazed, © Thalia Campbell Design, courtesy of The Peace Museum)

Pre-20th-century paintings play an important role throughout the exhibition, helping visitors to explore the changing ways humans have engaged with rural environments in Britain over centuries. For example, it features John Constable’s Flatford Mill (‘Scene on a Navigable River’), painted between 1816-17, which depicts a barge approaching a footbridge near to the artist’s father’s mill in the Stour Valley. In other parts of the exhibition, 20th-century interpretations stand in for particular paintings. A clip from John Berger’s analysis of Thomas Gainsborough’s Mr and Mrs Andrews (c. 1750) in ‘Ways of Seeing’ explores how this image is a celebration of private land ownership: ‘Without a doubt, among the principal pleasures this painting gave to Mr and Mrs Andrews was the pleasure of seeing themselves as the owners of their own land’. Elsewhere, the photomontage Haywain with Cruise Missiles (1980) by artist Peter Kennard subverts John Constable’s famous painting The Hay Wain (made in 1821), by inserting three nuclear warheads into the hay cart. Kennard created this piece in response to the proposal at the time to store US nuclear cruise missiles in rural East Anglia.

John Constable, Flatford Mill (‘Scene on a Navigable River’), 1816-17, oil paint on canvas, 101.6 x 127 cm, Tate, UK (Image: National Trust)

Peter Kennard, Haywain with Cruise Missiles, 1980, chromolithograph on paper and photographs on paper, 26 x 37.5 cm, Tate, UK (Image: Tate)

However, pre-20th-century artworks are primarily used in the exhibition as examples of ‘conservative’ tradition of landscape painting. It is an approach which seems to reinforce the assumption that pre-modern art is conservative when seen in relation to modern ‘radical’ art. The exhibition label describes Constable’s Flatford Mill as symbolising an idealised vision of rural Britain which ignores ‘the reality for workers at the time, who were being pushed away from the land through enclosure and the mechanisation of agriculture’. It goes on to explain that Constable’s landscapes have come to represent ‘the essence of Englishness’, used to promote ‘British art and culture abroad’ (including in school curriculums of nations colonised by the British Empire).

Yet this painting by Constable is not necessarily as rigidly conservative as its description makes out. As art critic Jonathan Jones explains, Flatford Mill depicts a horse ‘ridden by a boy who turns to make sure the tow rope [attached to the barge] is secure. Or is he enviously eyeing another lad who is having a happy day fishing? For this is a portrayal of child labour. Far from ignoring the miseries of his age, Constable honestly depicts them.’ These interpretations are not mutually exclusive, but instead serve to remind us of the nuances behind the landscape genre. This applies as much to contemporary ecological artworks, too. For example, the fact that Ruth Ewan’s Back to the Fields (2015-16) which ‘brings live plants and trees into the heart of the exhibition’ should not simply invite us to appreciate and celebrate botanical forms; it should also raise more uncomfortable questions about human tendencies to make sense of the natural world through domination and order. Of course, our views of such artworks do not need to be ‘either or’ - perhaps this exhibition ultimately succeeds in inviting us to complicate our understandings of how we interact with natural landscapes and settings.

Radical Landscapes is running at Tate Liverpool until 4 September 2022. Find out more here.

Ruth Ewan, Back to the Fields, 2015-16, installation including plants, bones, agricultural tools and minerals, dimensions variable (Image: Tate)

(Written by Esme Garlake on behalf of Athena Art Foundation, July 2022)