Nuestra Casa at The Hispanic Society: April Pick of the Month

Hermen Anglada Camarasa, Girls of Burriana (Falleras), 1910–11, oil on canvas, 148 x 211 cm, New York, The Hispanic Society of America (Image: Hispanic Society)

The Hispanic Society Museum & Library in New York has been closed for renovation since 2017, and it will finally re-open next year in 2023. Although many of its objects have been on tour and seen by museum-goers across the world, an exhibition in the museum’s newly renovated East Building Gallery now offers local visitors a sneak peek into their collection (which in total includes 750,000 objects). Its curator Dr. Madeleine Haddon describes how the exhibition aims ‘to show how far the Hispanic Society’s collection extends beyond the art of Spain, for which it has traditionally been known.’

The exhibition’s title ‘Nuestra Casa’ (meaning ‘Our House’ in Spanish) immediately reminds all visitors that they are welcome in the museum - it has free entry, and the museum has always seen itself as playing a critical role in the local community. Indeed, the museum is located in Washington Heights, an area of New York City which has one of the largest Latinx populations - although when it was founded by Huntington in 1904, the area was largely uninhabited. Not only does this exhibition celebrate the cultural heritage of Spanish and Portuguese speaking worlds, it also helps visitors to understand the centrality of Hispanic history for the identity of the United States.

Here are six showstoppers on display in the exhibition…

Agustín Arrieta’s Young Man from the Coast, after 1843

This is the first painting to greet visitors as they enter the exhibition. It depicts a young man from the Mexican coast. The young man depicted was most likely from Veracruz in Mexico, which was historically the first point of entry for slaves brought from Western African into Mexico. The painting is a testament to the large Afro-Mexican population in 19th-century Mexico, which still remains today. Dr. Madeleine Haddon notes that it was important for the exhibition to open with a painting that invited visitors to think about the complexities behind what it means to represent the Hispanic world.

Agustín Arrieta was a Mexican painter who tended to paint everyday scenes and still lives in his hometown Puebla, Mexico, where he lived for most of his life. Although we do not know the exact identity of the sitter in El Costeño, Agustín Arrieta depicts him with such familiarity and sympathy that it would be wrong to categorise this painting simply as a ‘type’ - rather, it blurs the boundaries between ‘type’ and ‘portrait’.

José Agustín Arrieta, El Costeño (The Young Man from the Coast), after 1843, 89 x 71 cm, New York, The Hispanic Society of America (Image: Wikipedia)

Velázquez’s Portrait of a Young Girl, c. 1640

This painting is paired with Agustín Arrieta’s El Costeño at the entrance of the exhibition. Like the painting by Agustín Arrieta, Velázquez’s sitter here is also anonymous. Although Velázquez often painted informal portraits of male sitters, it is rare to see one depicting a female sitter - in fact, this painting is his only portrait of a child who was not a member of the royal family. He has left the lower part of her dress unfinished, which gives an insight into the painting process, as well as giving a sense of informality and intimacy to this portrait.

Khalaf’s Ivory Pyxis, c. 966

This decorated box - known as a pyxis - is the oldest object in the exhibition. It is one of the most precious surviving objects from the Umayyad dynasty, and was made in 10th-century Cordoba, Spain. A pyxis was a cylindrical lidded container used to store jewelry, perfume bottles, cosmetics, or even poison. The inscription on this particular pyxis not only names the artist, Khalaf, who made it, it also explicitly notes that the object was made to hold precious perfumes (“a vessel for musk and camphor and ambergris”). The Umayyad were originally from present-day Syria who re-located to the Iberian peninsula in the 8th century, where they founded an independent state. The Umayyad had a huge impact on the art and culture of the Iberian peninsula, particularly through the visual motifs of flowers and foliage. Objects produced under the Umayyad are characterised by their intricate decoration, from luxurious boxes of carved ivory and gilt silver, to richly decorated architectural features (such as ornate marble capitals or fountains in palaces).

Khalaf, Pyxis, c. 966, ivory with chased and nielloed silver-gilt mounts, New York, The Hispanic Society of America (Image: Museum of Fine Arts Houston)

Goya’s Portrait of the Duchess of Alba, 1797

This is probably the most famous painting in the exhibition, and it depicts the Duchess of Alba in mourning clothes. The Duchess of Alba was one of the most striking figures at court in late 18th-century Spain, and here Goya seems to capture her air of charm and confidence. After her husband died a year beforehand, the Duchess retreated to her estate at Sanlúcar de Barrameda for a period of mourning; Goya joined her there, where he would create numerous portraits of her. In this painting, the Duchess points towards the ground at the words ‘solo Goya’ (‘only Goya’) which have been written in the sand, and she also wears two rings - one engraved with ‘Alba’ and the other with ‘Goya’. These details have often been used to support the speculation that Goya was romantically involved with the Duchess. Whether or not this was true, the pair certainly shared a close bond and the Duchess was an important source of inspiration for many of his paintings. In fact, Goya kept this particular painting in his studio long after the Duchess’ death in 1802.

Francisco de Goya y Lucientes, The Duchess of Alba, 1797, oil on canvas, 210.3 x 149.3 cm, New York, The Hispanic Society of America (Image: Hispanic Society)

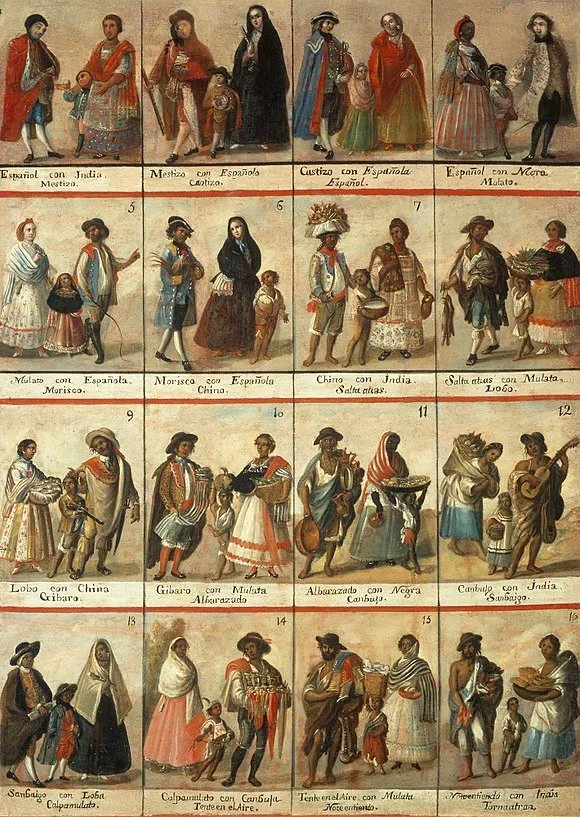

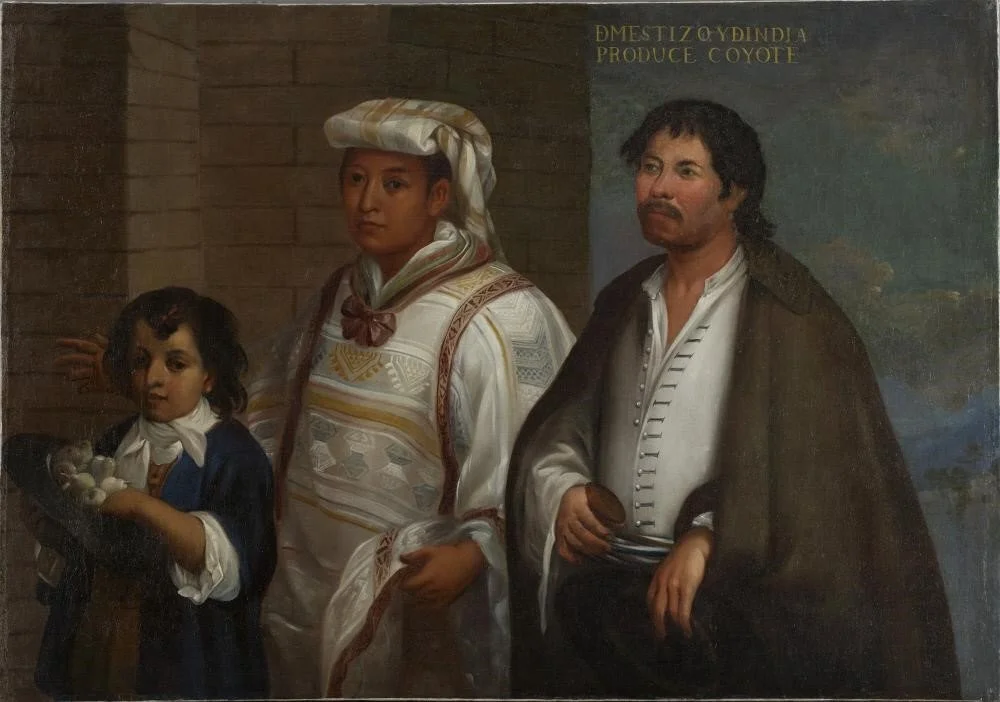

Rodríguez Juárez’s The Castas: Mestizo and Indian Produce Coyote, c. 1715

This painting was made within the ‘castas’ tradition which originated in the first decades of the 18th century. Casta paintings were made in series; in each one, a married couple with their offspring were depicted and labeled, as a way of visualising and codifying different racial mixtures prevalent in 18th-century Mexico. This painting, made by Juan Rodríguez Juárez around 1715, depicts a married couple and child. The husband is a mestizo man of European and Amerindian parentage and his wife is of indigenous Mexican descent. Their son is given the nickname ‘Coyote’, in reference to his particular racial heritage according to the Spanish colonial perspective (which includes that of the artist). The family are elegantly dressed and details such as the boy’s basket of white pears and his father’s box of snuff or tobacco all remind viewers of this family’s relatively comfortable social status. By creating distinct social and racial hierarchies (in large part through Casta paintings), the Spanish were able to maintain authority in the New World.

Anonymous, Casta painting showing 16 racial groupings, 18th century, oil on canvas, 148 x 104 cm, Museo Nacional del Virreinato, Mexico (Image: Wikipedia)

Juan Rodríguez Juárez, The Castas: Mestizo and Indian Produce Coyote, c. 1715, oil on canvas, 103.8 x 146.4 cm, New York, The Hispanic Society of America (Image: Hispanic Society)

Joaquin Sorolla y Bastida, After the Bath, 1908, oil on canvas, 176 x 111.5 cm, New York, The Hispanic Society of America (Image: MCAH)

Sorolla’s After the bath, 1908

Sorolla painted this on a Valencian beach in the summer of 1908 - we see the artist’s typically free brushstrokes to create a vibrant and bright scene of sun and sand. One year later, the painting was exhibited at the Hispanic Society for the first time - this first tour of Sorolla’s paintings attracted 160 thousand visitors. Sorolla was a contemporary of Huntington, the founder of the Hispanic Society, and some of the first exhibitions at the museum were retrospectives dedicated to the artist.

Nuestra Casa: Rediscovering the Treasures of The Hispanic Society Museum & Library will be touring to Ontario later this year, and in 2023 it will visit the Royal Academy of Arts in London.

Listen to Dr. Madeleine Haddon speaking to Athena Art Foundation’s Director Dr. Nicola Jennings about this exhibition in detail on the latest episode of Athena Asks podcast:

(Written by Esme Garlake on behalf of Athena Art Foundation, April 2022)