Paul Gauguin and the 'Other': June Pick of the Month

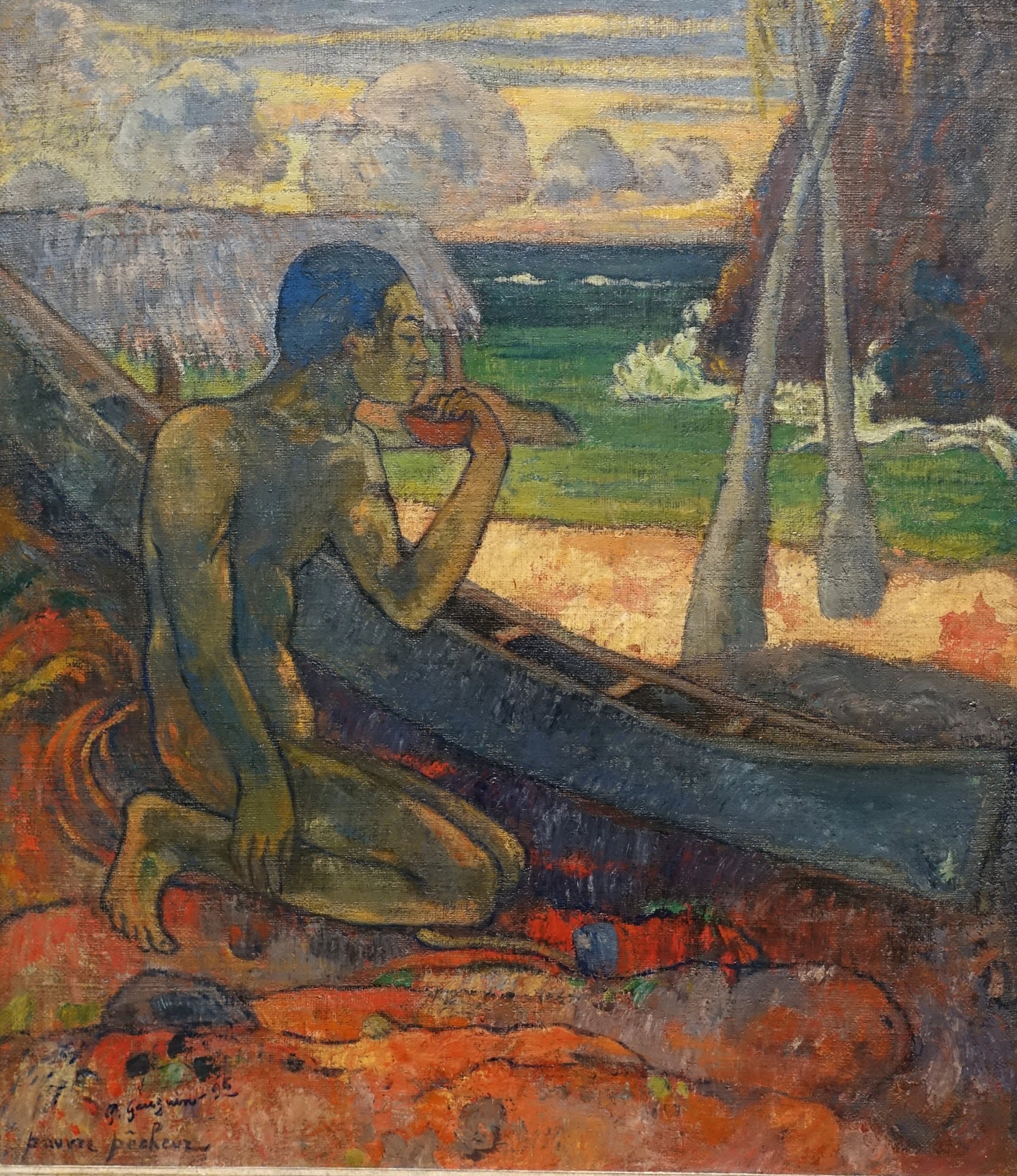

This June, we would like to draw attention to a landmark exhibition exploring the art of Paul Gauguin, currently taking place at the Museo De Arte De São Paulo in Brazil. ‘Paul Gauguin: The Other and I’ is the first exhibition to have Gauguin’s relationship with the ‘other’ as its central critical focus; the ‘other’ being images of landscapes and people from outside the European cultural panorama. The fact that this exhibition also emphasises Gauguin’s personal links to Latin America is especially interesting, particularly given its location in Brazil (and curation by Brazilian scholars). It brings together 40 works by Gauguin, including paintings and engravings; primarily his self-portraits and the works he produced whilst staying in Tahiti (the largest island in French Polynesia). So, what drew Gauguin to Tahiti to paint?

This exhibition provides a useful insight into the visual material created by this seminal artist to showcase and highlight the racial stereotypes surrounding Tahitia people specifically but also people of colour more widely, thus it is an important exploration of the development of racist stereotypes during this period and on a larger scale. The exhibition takes a deep dive into Gauguin’s paintings of Tahitian people and landscapes, which tended to reinforce a view of Tahitians as exotic, primitive and ‘other’. His artworks emphasised an idealised vision based on stereotypes and fiction, which set the ‘artist’s ‘I’ against the ‘other’. At the same time, Gauguin combined iconographies from various cultures which often invited a more critical exploration of Western painting traditions.

The exhibition has also positioned Gauguin’s works within MASP’s annual programme dedicated to Indigenous Histories. It includes a number of works by Indigenous artists, such as Carmézia Emiliano, Sheroanawe Hakihiiwe and Melissa Cody. There are also pre-Columbian ceramics and metals on display, lent by Edith and Oscar Landmann (the former president of the São Paulo Biennial).

Self-Portrait (near Golgotha), 1896, Paul Gauguin (Image: Wikipedia)

Who was Paul Gauguin?

Paul Gauguin was a French Post-Impressionist artist, generally considered to be one of the most important modern French artists of the 19th century (even though he only became internationally recognised after his death in 1903). The exhibition reminds us that Gauguin’s mother was Peruvian, and that the artist spent time in Lima, Peru, as a child; later in life, he would emphasise his ‘Inca blood’, and refer to himself as ‘primitive’ and ‘savage’.

It was only at the age of 35 that he decided to fully dedicate himself to being a painter. His experimental use of colour moved away from Impressionism, and he was part of a group of artists working in Paris during the late 1880s and early 1890s who pioneered the Synthetist style (which emphasised two-dimensional flat patterns). Towards the end of his life, he spent ten years in French Polynesia, where he created paintings of people and landscapes from the region. Today, these paintings are increasingly viewed in relation to Gauguin’s sexual relationships with teenage Tahitian girls, as well as the legacy of European colonialism in his work.

Case study: Arii Matamoe

Image: Wikipedia

Gauguin painted Arii Matamoe (also known as The Royal End) in 1892 during his first visit to Tahiti. It shows a man's severed head on a pillow, laid out in front of mourners, almost as if a still-life composition. The painting may also have been inspired, in part, by the death of Tahiti’s last monarch, Pōmare V, in the previous year. The implied connection between Tahitian culture and violence was in keeping with racialised views spread by ethnographic descriptions in 19th-century Europe that portrayed the peoples of the Pacific as constantly at war.

The crouching figure in the background (which also appears in earlier works by Gauguin) refers to a Peruvian mummy that the artist saw in Paris in the Musée Trocadéro, demonstrating how Gauguin was drawing upon many different motifs and symbols which were not just in Tahiti, but also from around the world (made possible by colonial extraction). Art historian Scott C. Allan has noted that the painting, “though prompted by the painter’s initial experiences and encounters in Tahiti, is more deeply and inevitably a self-mythologising work… a kind of symbolic self-portrait in which the artist expressed his profound disenchantment with present realities [and] gave fetishistic form to self-aggrandising fantasies of victimhood and martyrdom.” Indeed, the way in which Gauguin described the painting in a letter to his friend emphasises his awareness of the power of his own artistic vision and creations: “I have just finished a severed Kanak [Pacific Islander] head, nicely arranged on a white cushion, in a palace of my invention and guarded by women also of my invention.”

Case study: Arearea no varua ino

Image: Wikipedia

Image: Met Museum

This painting Arearea no varua ino (Words of the Devil) shows bathers at the water’s edge, a frequent motif in Gauguin’s depictions of Tahiti that reflected his view of Tahitians being connected to nature. We see two women in a brightly coloured natural landscape. One woman is washing her hair, whilst the other is seen in profile with a stern expression that echoes the statue of Hina behind her. In Polynesian origin myths, Hina (mythical goddess of the Moon) reasoned with the god Tefatou to ensure the rebirth of humanity. Although it features Tahitian themes, Gauguin created this painting in Paris, where he lived for a two-year break between times in Tahiti. It is therefore not an observed scene, but an imagined one.

The exhibition draws attention to the eroticisation of the women’s bodies here - as in so many of Gauguin’s paintings - and invites viewers to consider how their supposed sexual availability would have appealed to white European male viewers at the time. We also see this in Two Tahitian Women (right), in which two bare-chested Indigenous women stand in front of the viewer; one holds a tray of ripe mango, the other reveals one of her breasts. Interestingly, this was one of the first paintings by Gauguin to be critically questioned from a feminist viewpoint in the early 1970s.

(Written by Esme Garlake on behalf of Athena Art Foundation, June 2023)